2015: A new dawn for Baghdad?

BAGHDAD - On a balmy mid-June day in central Baghdad, scores of Iraqis gather in a tented area in the grounds of the Al-Mansour hotel to break their Ramadan fast.

Alham Ramadan, hosted by imported Egyptian TV hosts, is broadcast live on Iraqi TV and features an array of Baghdad's movers and shakers, all gathering to enjoy the masses of food and drink that make up the Iftar meal.

At $35 a ticket - $60 if you want to stay for the music and dancing until 1am – it's an event that most Iraqis aren't likely to attend.

The merriment, with barely a headscarf in sight and more than a few well-groomed metrosexuals, hardly hints that barely 57km away are the Islamic State (IS) - referred to as "Daesh" by Iraqis - edging on the city's borders.

While Baghdad may be a city still synonymous internationally with car bombs, sectarian violence, kidnappings and fanaticism, military and political officials have been keen to stress that sectarian bloodshed of 2006-7 and the frequent car bombs that followed the rise of IS, are a thing of the past.

“We opened an office responsible for buying and selling all the cars in Baghdad,” says Lt Gen Abdul Amir al-Shammari, head of Baghdad Operations Command (BOC).

“We made a contract between this office and the people in Iraq, submitted by the BOC commander and nobody can buy or sell any cars without our permission. This year, 2015, until now there have been no car bombs.”

Such confidence seems premature - only on Sunday 11 people were killed when a car bomb exploded in Baghdad’s Amil district, following the breaking of the Ramadan fast. Another car bomb also killed two people in the town of Balad Roz, just north of the city.

“The enemy have good skills for car bombs and we exposed that,” Shammari told Middle East Eye.

“Maybe in the future there will be no car bombs.”

Such optimism doesn't clearly translate to Baghdad's streets. Armoured vehicles, truck-mounted machine guns and AK-47s are a constant sight, while checkpoints appear every five minutes and virtually every road is laden with concrete protection blocks.

Leaving the confines of hotels or the reinforced vehicles that carry most of Baghdad's foreign visitors is heavily discouraged, particularly for journalists. Bomb scanners and metal detectors are ubiquitous.

The Baghdad Operations Command itself is located within the Green Zone, a heavily fortified area of the city which used to host the American occupation forces and is still the main base for foreign visitors and the city’s political and social institutions.

The BOC currently functions as the main base of operations for the defence of the city, with a myriad network of cameras set up with rapid deployment forces ready to rush to the scene of any disturbance. It also facilitates and strategises with army operations in neighbouring provinces, such as IS-controlled Anbar.

“We have a joint room with the [US-led] coalition forces, and this joint room we can gather from it information, sometimes sharing this information, analysing this information and, sometimes, when we have the concrete decision about an airstrike,” said Brigadier General Saad Maan Ibrahim, from Iraq's Joint Operations Command.

“We are in touch with so many people in Mosul and Fallujah and some of them are providing us with information about any movement from Daesh or meetings or something else – if we are talking about psychological warfare, also, they are ready for the coming of our units.”

Dreams of safety

In the “Red Zone” that comprises the non-Green Zone areas of the city, pictures of Imam Ali - the son in law of the prophet Muhammad who is central to the Shia sects - are everywhere, as well as photos of Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, anti-occupation militant Muqtada al-Sadr and leader of the Shia Islamic revival, Ruhollah Khomenei.

It stands as a reminder that Baghdad is a city which saw much of its Sunni population driven out, leaving previously mixed neighbourhoods now majority Shia.

Fatima, a 22-year old media student from a mixed Sunni-Shia family in Baghdad, remembers the height of the city's sectarian violence in 2005.

"We were helping our neighbours, who were Sunni," she said. "The Shia were robbing their houses and we stood against them which made them mad at us. So they kidnapped my father."

Since those dark days (her father was freed after they paid a ransom) the situation in Baghdad improved, with the threat of car bombs fading into the background.

"We can’t say ‘if we go outside we will die’. We have to live our lives," she said. "I’m very grateful for the army of Iraq and the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMUs). They are sacrificing their life to protect us.

"I am safe here."

A return to safety and a degree of security is now all many Baghdad residents hope for. Iraq is a country that has hardly known two years of peace (or freedom from crippling sanctions) in the last 35 years and there are signs that some Iraqis have all but abandoned the idea of ever seeing a peaceful, unified Iraqi state.

Baghdad’s 12-year old curfew was lifted in February, along with the banning of weapons in four neighbourhoods of the city, allowing a semblance of normality to return to Baghdad. Liquor stores, malls and clubs have reopened and - for those who can afford it - there is an opportunity to glimpse the Baghdad that was once one of the world’s cultural hubs, before the onset of war, sectarianism and poverty.

'It's safe - but be careful'

Baghdad’s governor, Ali al-Tamimi, was keen to stress that visitors to his city should no longer feel threatened by its notorious reputation.

“I think that Baghdad is very safe and I want them to come to here and visit Baghdad, Arabs and foreigners, to see with their eyes what exists in Iraq,” he told Middle East Eye.

“But I would recommend that when they come to Baghdad they coordinate with the security forces of the Baghdad governorate if, say, they want to visit a restaurant.”

A large imposing man, Tamimi is a veteran of the Sadr movement, a Shia Islamist revival led by the charismatic preacher Muqtada al-Sadr which took a strong position against both the American occupation of Iraq and the sectarian hardliners of al-Qaeda in Iraq, the group who later morphed into IS.

The movement’s adherents - while officially opposing sectarianism - have been accused of ethnically cleansing parts of Baghdad of its Sunni population and driving them into the hands of Sunni radicals.

Though Tamimi is keen to emphasise that such hostility is in the past (“I am a Shia, but I love Sunnis!”) he acknowledges that there are pockets in and around the city where IS still have a foothold.

“We can say that there are small places, small locations, which exist in Abu Ghraib and Tarmiyah - we could say that these are not safe. Daesh cannot operate without other people’s support.”

The fall of Anbar province to IS in May alarmed many observers because of the province’s proximity to the capital.

The Iraqi army’s retreat from the capital of Ramadi - a move later described as “unauthorised” by Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi - raised fears that the militants could then set their sights on Baghdad.

However, a new offensive led by the Iraqi army and the PMUs - usually referred to as Shia militias in foreign media - against the province has begun to make inroads.

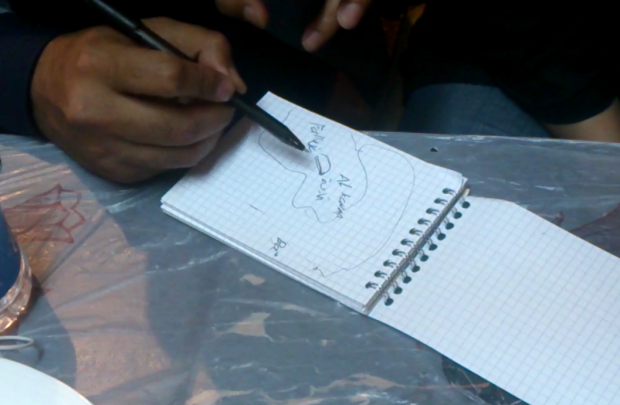

Brigadier General Saad Maan Ibrahim, from Iraq's Joint Operations Command, took MEE through the strategy on paper.

“Now, we are in all these areas,” he said, indicating the areas north and south of Al-Karmah on a map. He said that the only way for Daesh now to advance was from the east, as the areas west of Baghdad - between the city and Al-Karmah - had been liberated from IS fighters as well.

“Their strategy is still keeping fighting in Al-Karmah, not giving us a chance to be in the areas between Al-Karmah and Fallujah,” he explained. “You can imagine that if we tackle Al-Karmah 100 percent, Fallujah will be encircled.”

The call to arms by Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani - Iraq’s highest Shia authority - in June in 2014 following the IS takeover of Mosul, was a major turning point in the conflict, with hundreds of thousands of Iraqi Shias taking up arms to fight against the Sunni militants.

Abdul Amir al-Shammari described Sistani’s fatwa as heralding the moment when the previously besieged security services in Baghdad were able to switch from a defensive strategy to offensive, coupled with the US air support.

But the PMUs have proven controversial due to their perceived sectarianism and accusations of human rights abuses.

In April, Human Rights Watch lambasted Iraq’s US allies for not doing more to counter the PMUs influence and highlight their abuses.

“ISIS poses a terrible threat to civilians in Iraq, but that’s no reason to pretend that paying lip service to human rights is an adequate response to the militia abuses,” said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “President Obama needs to tell Prime Minister Abadi that militia revenge attacks won’t be tolerated.”

Sectarian claims 'exaggerated'

The original operation to recapture Ramadi in Anbar was named “We Obey You, O Hussein” – a reference to the Prophet Muhammad's second cousin, venerated by Shias – by the PMUs, though they changed it to “We Obey You, O Iraq” after pressure from the government.

But Saad Maan attributed much of the fear around sectarianism to propaganda campaigns by IS.

"It is psychological warfare against our people," he said. "Most people in Al-Karmah are Sunni and we have more than a thousand people from the tribes there that are fighting with us against Daesh [IS]."

He conceded that most of those fighters in the PMUs were Shia - though he added there was no recorded breakdown of numbers by sect - but claimed that sectarian division were exaggerated.

“Daesh are trying to create problems between the Iraqi sects and the Iraqi religions,” he said. “On the ground, I think this doesn't exist.”

While he said that the army was in no position to refuse help from the the PMUs at the moment, he also hinted that they would not be a permanent fixture.

"I know that not all of them are angels," he said. "We are needing them [PMUs] for this period only. But next year the situation may change."

Maan said that considering the progress of the campaigns - coupled with a new supply of F-16s and support from the US - the defeat of IS would not be far away.

“All in all, I think it will be less than one year.”

Baghdad governer: US wants revenge

Not everyone is happy about the Americans’ return to Iraq and some, such as governor Tamimi, have an altogether different theory about US aims in the country.

“I think they want to make a kind of mess situation between Sunni and Shia Iraq in order to save Israel,” Tamimi told MEE.

“Some of the American pilots and American airforce are hitting Iraqi forces and the PMUs and leaving Daesh,” he said, adding that they “found weapons in the ISIS group manufactured in Israel.”

“If they [the Americans] wanted to get rid of Daesh they could do it in months.”

“The Iraqi people have fought the American army and we think that they want revenge,” he added. “This is not only me who said this, the leaders of the PMUs have said the strikes are not accurate. The PMUs liberated Samarra and Amerli without any strikes.”

Tourists still coming

Iraq still receives millions of tourists each year and there is a regular flow to Baghdad of visitors wanting to experience the shrines and mosques of the ancient city.

Tamimi promised the creation of 100,000 new homes, as well as schools, parks, police stations, city halls and civic centres, playgrounds, shops and sports facilities as part of the Bismayah New City project. Constructed by the South Korean company Hanwha, the new city is expected to be completed by 2019 and is set to house around 600,000 residents.

"I have a vision in the future to make Bismayah a district in Baghdad," he said, adding that he would "coordinate with the national investment for each ministry to have a number for their employees."

Though the situation has improved greatly since the mid-2000s when the city was routinely described as "hell", Baghdad is far from being free of violence - sometimes from its own protectors - and it remains to be seen whether the will of its citizens will hold up in the face of an uncertain future.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].