Refugee crisis builds at Syria's border with Jordan

AMMAN - Jordan’s newest camps for Syrian refugees are being built not amongst the deserts and urban sprawl of northern Jordan, but on the far-flung badlands of the eastern desert, on the southern fringe of Syria itself.

Here, in a demilitarised zone between the two countries, a rapidly growing outflow of Syrian refugees is hitting the limits of Jordanian hospitality. This week, Jordanian authorities and the NGOs that offer basic services estimate there are between 16,000 and 17,000 people marooned on the frontier.

A security-first directive

Of all Syria’s neighbours, Jordan has maintained the most controlled border policy throughout the nearly five-year conflict, and it is arguably the most stable. The terrorist attacks of Beirut, Baghdad, Erbil, Ankara and Istanbul are yet to rattle Amman, and Jordanian authorities are determined to keep it this way, which means prioritising security – a far-reaching directive that includes complex screening for refugees wishing to enter Jordan, and a vastly reduced intake.

Officials have, for the past two-plus years, maintained strict control over the flow of refugees into the kingdom, which officials say already shelters 1.4 million Syrian refugees – about 20 percent of the population. From a high of several thousand refugees per day in 2012, Jordan now admits an average of 50-100 people a day, and on some days, none at all.

But as Syria’s war grows more vicious and protracted, the refugees keep coming, streaming south through the demilitarised zone between the two countries until they press up against the man-made earthen strip that marks the northernmost edge of the reach of the Jordanian military. And here, in their thousands, they wait.

The long road south

Syrians from all over the country pay smugglers to pack them into trucks – “Like sheep,” said one middle-aged mother who had made the journey – and drive them through government-held territory through the eastern desert. The days are long, the roads are bad and there is little food or water on a journey that can take up to 21 days.

Israa al-Nasser, a young mother who was granted entry to Jordan on 14 January after spending three months on the berm, told Middle East Eye she paid smugglers around $430 to make the three-day journey. Her two small children rode free, she said bitterly.

According to Brigadier General Saber Taha Al-Mahayreh, who heads the border forces responsible for policing Jordan’s Syrian and Iraqi frontiers, smugglers take their human cargo into the demilitarised zone through any number of routes, but drop them off at one of 12 neighbourhoods or gathering points.

As the number of people seeking refuge via Jordan’s northern border has exploded – from 3,000 in late September, to 12,000 in December to 17,000 this week – these gathering points have swollen into what Mahayreh calls “semi-camps”.

Policing the borders, facilitating NGO access and carrying out the lengthy security and health checks required to admit refugees costs the Jordanian military manpower, equipment and vast sums of money. Mahayreh said the bill was close to $700mn since the start of the crisis.

“This is our human duty and we all need to take part in this national burden,” he said. “But Jordan cannot take this whole thing on alone.”

A crisis on the ridge

The logistical and economic challenges posed by the build-up on the ridge have been compounded by the growth of the groups at two main crossing points: Ruqban, on the far eastern tip of the border, where 16,000 people, mostly from eastern Syria, have gathered, and Hadalat, 100km to the west, where around 1,300 people from Damascus and the southern province of Daraa have arrived.

More people on the strip mean a greater need for supplies – water, food and medicine – tents, medical aid and logistical support. The border guard forces work with a half-dozen civil society groups and NGOs including the UN and the Red Cross to keep the humanitarian situation in check, but at Ruqban in particular, the situation is desperate.

According to a Red Cross situation report, in the first week of 2016, at least five people died at Ruqban, including two children. Five babies have been delivered so far at the border while 1,336 of Ruqban’s women are pregnant.

The size of the group on the strip has also become a security challenge in itself: while it’s easy to obtain the names of a group of 500 or 1,000 people, the makeup of the group at Ruqban is less knowable.

"The people on the border is a worry. Although they don't have military equipment, 16,000 or 20,000 people is a problem,” said retired General Ali Shukri, a former aid to King Hussein.

The Russia factor

The explosive growth of the group at Ruqban can be attributed to Russia’s deepening involvement in the Syrian war, and in particular, Russian airstrikes.

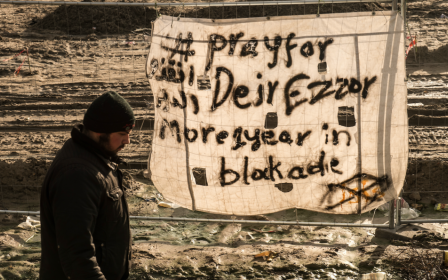

Border force boss Mahayreh said the majority of people at Ruqban came “[in a] short period of time, when attacks intensified.” He noted that early arrivals came from Homs and Idlib, areas targeted by Russia’s first strikes in late September and early October, and NGOs say recent arrivals hail from Aleppo, Raqqa and Deir Ezzor – areas under continuing, heavy bombardment. These areas are also under the control of the Islamic State militant group (IS), which has repercussions along the border.

In an interview with CNN earlier this month, Jordan’s King Abdullah explained, “Part of the problem is that they have come from the north of Syria, from Al Raqqa, Hasaka and Deir Ezzor, which is the heartland of where [IS] is. We know there are [IS] members inside those camps.”

He continued, “[From] a humanitarian point of view and a moral point of view, you really can’t question our determination, but this particular group has a major red flag when it comes to our security.”

While they agree that preserving Jordan’s peace is paramount, NGOs say people who are running from terrorism – particularly women, children and the elderly – should not be viewed as terrorists. Lengthy and detailed security checks on the border may help some legitimate refugees reach safety, but diplomats pressing for Jordan to open its borders say not enough is being done.

“These people are not fleeing IS. They are seeking safety on Jordan's border away from coalition bombing. The large group in Ruqban comes from Daesh [the Arabic name for IS] areas and will not be let in,” said a senior European diplomat, speaking off-the-record so as not to damage relations with Jordan.

As the size of the group grows, its very existence becomes a security issue as well as a humanitarian challenge – something this diplomat believes will play into the security-first narrative and further endanger refugee lives.

“We will have a protracted emergency on the border. I am deeply concerned how this will play out."

If Russia moves south

The other major variable along Jordan’s border is what happens next in largely rebel-controlled Daraa province. Between 28 December and 3 January, Russian warplanes carried out a blitz of airstrikes on Sheikh Miskeen, a Daraa village near the Brigade 82, one of the Syrian army’s largest bases in the southern province of Daraa.

After years of heavy fighting and a year under rebel control, Sheikh Miskeen and its surrounding areas were largely depopulated, and the intense bombardment – including up to 60 strikes in one 48-hour period – didn’t trigger widespread displacement: there was no population to displace.

But if Russian planes were to turn their might on a more populated rebel-held stretch of Daraa, the flood of people on the run would have nowhere to go but south – to Jordan. This situation could quickly spiral into a humanitarian catastrophe and a security nightmare for the border guards who maintain that frontier from the Jordanian side.

Retired General Ali Shukri told Middle East Eye he doesn’t think it will come to this, given Jordan’s diplomatic ties with Russia.

"I don't think the Russians will allow the rebels to come closer to Damascus. They will do anything and use everything to stop them. And if it's about stopping them, that's one thing. But if it's about pushing them out, this becomes an issue for Jordan,” he said.

Shukri ultimately thinks this is all designed to prolong the province’s stalemate: "I don't see the Russians pushing those rebels in Daraa to the point where they have to run away and into Jordan – I don't think that is on the books."

But regardless of what happens in Daraa, Jordan is ever more acutely feeling the consequences of the entirety of the Syrian war. A small country with few natural resources in a tough neighbourhood, plucky Jordan has done more for Syria’s refugees than most other countries in the region – and certainly more than wealthier, more able Western states.

The cost of maintaining security may be visible now in terms of refugee lives endangered and lost, but the cost of losing control and seeing its own security fractured would doubtless be far harder for Jordan, and its allies, to stomach.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].