Syria's buffer zone: Rebels, Turks and civilians rush to implement the Sochi deal

DE-MILITARISED ZONE, Syria – With the autumn sun setting behind him, Hassan Abu Ahmed inspects the crumpled heap that was once his relative's house.

"Thank God no one was hurt," he sighs in relief. "The shell hit a wall and caused the house to collapse. It will need a lot of restoration."

Abu Ahmed lives in the village of al-Lataminah, in the north of Syria's Hama province, which happens to be within a buffer zone that Russia and Turkey hope will stave off a bloody assault on northern Syria.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin announced the agreement to create a 15-20km de-militarised zone between Syrian government and rebel forces on 17 September in the Russian city of Sochi, just as it looked like an assault on the rebels' final redoubt looked inevitable.

For Syrians like Abu Ahmed, living on the front line between the rebels and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's troops, the announcement came as a huge relief, and already he is seeing a difference.

"Since the announcement of the agreement, the bombing has calmed relatively, contributing to the return of more than one-third of the population of the village [approximately 1,000 families]," he told Middle East Eye.

Abu Ahmed stayed, however. He said that although the area is now safer, there is still danger.

"The heavy weapons that government forces must withdraw from the vicinity of the fronts are still targeting the area sporadically," he said.

When Abu Ahmed's uncle’s house was recently targeted, his daughter lost a leg and his son lost an eye.

"Look at the reconnaissance planes flying in the sky that can see the entire town and monitor any civilian gathering," he said.

Heavy weapons withdrawn

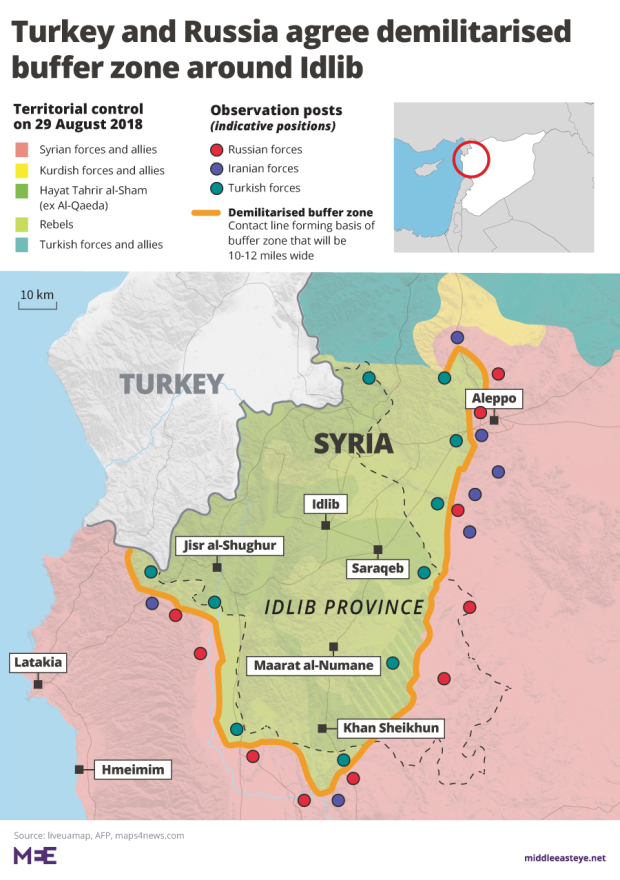

The buffer zone stretches from a few kilometres northwest of Aleppo city, down through Idlib province’s east and round northern Hama up to the border between Turkey and Latakia province.

The area covers a complex military landscape, containing various rebel groups – some more militant, such as former al-Qaeda affiliate Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, and other, more nationalistic ones.

Turkish observation points look out at Russian and Iranian ones on the other side of the divide.

According to Erdogan and Putin's deal, all heavy weapons will be pulled from the buffer zone, and the area will be rid of militant groups such as HTS.On Wednesday, the first part of the pact appeared to go off without a hitch, as the deadline for all heavy weapons to be pulled out of the buffer zone passed with seeming success.

According to a leader of rebel group Jaish al-Azzam, a faction based around al-Lataminah, ridding the area of heavy munitions wasn't as difficult a task as some might have thought.

He said most of the heavy weapons were kept in warehouses away from the front line, to be brought out and moved closer when heavy fighting erupted, so they merely stayed there.

Captain Naji Mustapha, spokeman for the National Liberation Front rebel group, told MEE that rebels coordinated with Turkey as they withdrew their heavy weapons.

"We will keep our deployment points in the front lines fortified with medium and light weapons," he told MEE, "and we will continue to equip our forces on defense lines in the buffer zone in anticipation of any emergency."

Part of the Russian-Turkish plan seeks to open the highly important M5 highway that runs between Damascus and Aleppo, via Hama and the Idlib countryside.

Though the Syrian government has held all three cities for some time now, the rebels' presence along long stretches has kept this artery closed.

They told MEE that if the M5 is opened, commerce can return to their villages.

'Cessation of jihad'

The second phase of the deal’s implementation is set to prove far more difficult, however.

Monday sees the deadline by which all hard-line rebels must have pulled out of the buffer zone. Some, such as the Ansar al-Din Front, based in southern Aleppo, quickly issued a categorical rejection of the entire terms of the Russian-Turkish agreement.

The militants said that the agreement was tantamount to surrender and the declaration of a cessation of jihad in the opposition areas.

The key militant group in north Syria, HTS, has so far kept tight-lipped over the September Sochi deal.

Turkish security sources told MEE that around one-third of HTS's 15,000 fighters have been operating in the buffer zone. Of that third, around 1,000 have withdrawn, according to the sources.

On the ground, not much HTS movement has been witnessed.

Perhaps tellingly, however, HTS has been allowing free passage to Turkish troops moving through the Bab al-Hawah border crossing it controls and into positions around Turkey's observation points from which they can move against other militant groups.

According to the FSA commander, these forces can move at any moment against any forces that could impede the application of the buffer zone agreement or disrupt Turkish military patrols.

Many opposition factions are deployed in the villages of Jisr al-Shughour and Latakia, such as the National Liberation Front, and two al-Qaeda-inspired groups, the Turkestan Islamic Party - made up of Uighurs from China - and Hurras al-Din. On the other side, Iranian-backed Shia forces loyal to the Syrian government are deployed.

The possibility of an outbreak in violence between Turkish troops and these groups is high.

Hurras al-Din has rejected all the terms of the Russian-Turkish agreement and called on all fighters to start military operations that will scupper any international deals.

The TIP, meanwhile, has been digging trenches around its positions in northern Latakia, according to Russian media, showing no signs that it is willing to pull out.

'The loss of our land'

Rebels aren't the only people in the area unhappy with the deal.

In Sarman, a village in the buffer zone southeast of Idlib city, dozens of Arab tribesmen gathered in front of a Turkish observation point, demanding Ankara seeks further concessions from the Syrian government and its Russian ally.

Khalid Suleiman, a displaced civilian from the eastern Hama countryside, told MEE: "We call on the Turkish government to pressure the Syrian government to withdraw its military forces from the east of the Hijaz railway and implement the Astana agreement."

Since then, Syrian government forces have chipped away at the area supposedly covered by the agreement, after conquering three other designated zones.

For the people displaced by the Syrian government assault on the de-escalation zone's south, especially around the strategic Abu al-Duhur military air base, the new Russian-Turkish deal is a downgrade on the one signed in the Khazakh capital.

Eid al-Husain, another displaced person at the demonstration, told MEE: "More than 400,000 people have been displaced by the attack and are now displaced in the random camps. We see with our own eyes that the tanks of Damascus are moving in our villages.

"We cannot return to our land with the presence of Russian forces and pro-Syrian government forces," Husain added. "The Sochi agreement is like redrawing borders and means the loss of our land."

Preparing for failure

Pro-government forces, it appeared on Friday, were preparing for the deal to fail.

Syrians close to the front line received messages on their phones warning them to steer clear of militants in the area.

"Get away from the fighters. Their fate is sealed and close," one message said.

"Don't allow the terrorists to take you as human shields," read another.

Among all these political and military complexities, meanwhile, 10-year-old boy Ahmed Kadoor sits with his friend amidst the destruction in al-Lataminah.

If the deal does hold out, and Erdogan and Putin's plans come to fruition, Kadoor may be stay in the school he has only recently returned to. He is determined to whatever the outcome.

"I couldn't study last year as a result of the indiscriminate bombardment and the disruption of the schools," he told MEE.

"Now I have been enrolled again in the second-grade school. I will continue to study this year, regardless of whether the bombing stops, continues, or returns."

Ece Goksedef contributed to this report

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].