Tawergha - 'a scar on Libya's revolution'

“The children born in refugee camps haven’t harmed anyone.”

The children born in the seven days after the “Liberation of Tawergha,” during Libya’s 2011 revolution celebrated their third birthdays last week.

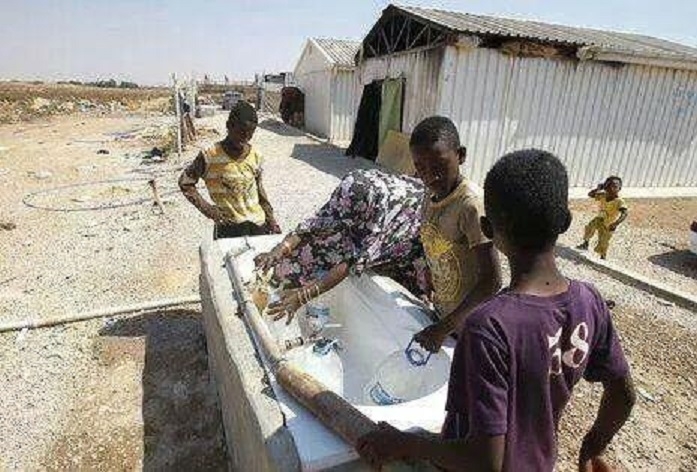

But for most of them, the date will have been marked not with candles and cake, but with another instalment in the daily struggle for clean drinking water and basic rights. These children have lived their whole lives in squalid refugee camps dotted throughout Libyan cities - they have never seen their hometown of Tawergha, the “green island” of Berber tradition.

Now, three years on from the forced evacuation of around 40,000 of the city’s residents, Libyan authorities and the United Nations are coming under increasing pressure to find a lasting solution for displaced Tawerghans.

‘A scar on the face of Libya’s revolution’

The city of Tawergha effectively became a ghost town on 11 August 2011, as rebels from nearby Misrata launched an all-out offensive.

The violence of 11 August didn’t come out of nowhere, though. There had been tension between Tawergha and Misrata for years; there were widespread allegations of killings and violence against women committed by men from Tawergha against Misratans, according to Sam al-Sharksy, a British-Libyan activist based in the UK.

When the 2011 uprising rolled around, the guns and rockets of war ignited long-running tensions between the towns. Tawergha was used as a base for Muammar Gaddafi’s forces, who between early March and mid-May subjected the neighbouring town of Misrata to a punishing three-month siege. Later, as rebels began to gain the upper hand, Tawerghans accused of complicity in the blockade of Misrata became a prime target. In its annual report published on Thursday, the Libyan Victims’ Organisation for Human Rights (VOHR) documents the arbitrary arrest of thousands, the abuse and torture of civilians and ultimately the wholesale expulsion of the city’s population, in what Human Rights Watch calls an act of “ethnic cleansing.” VOHR calls what has happened to the Tawerghans since then “a scar of the face of Libya’s revolution.”

‘Mass detention centres’

Three years on, and Tawerghans have made little progress towards returning to their homes in what is now a ghost town. Most live in cramped refugee camps on the outskirts of major Libyan towns.

“The camps are inhumane - there is no clean running water, no toilets, no security. Those who visit usually come out crying,” according to Sharksy, who has started a Twitter campaign to draw attention to the issue.

VOHR has also documented numerous attacks on the settlements, which are “closer to mass detention centres” than refugee camps. In the most recent, a July 2013 attack on al-Fallah camp in central Tripoli, a refugee was killed and several injured when militias walked in and opened fire. Such assaults and killings have, according to the VOHR, been met with stony silence by the Libyan authorities.

Government and UN failures

The years since the “Liberation of Tawergha” have been characterised by silence from the government - but many also criticise the inaction of the United Nations.

“For the Libyan government, it is very difficult to get Tawerghan problems on the agenda,” according to Andrew Allen, charge d’affaires for the British embassy in Libya. “In the past year, there has only been one high-level meeting on the issue.”

The government has put forward one suggestion for a lasting solution - that Tawerghans relocate to the town of al-Jufra. Over 350 kilometres south of Tawergha in Libya’s scorching desert, the refugees recently rejected it as a possible site for their new home. No new solution has been put forward to date – “despite all the international laws and procedures, the Libyan government has not made any earnest efforts to return the city’s residents to their homes,” reports VOHR.

Activists also complain about the role the UN has played in the protracted dispute. Jeroen Spaander, a Dutch businessman who runs the campaign group, Tawergha Foundation, told MEE that there are just three UN staff working on the ground with Libya’s over 50,000 internally displaced people. “The UN can’t do very much. They need approval from the people in charge - but the people in charge are actually militia groups.”

Andrew Allen told MEE that, though the UN in Libya have had some success, including in their work with Tawerghans, "they have some difficulties. I don't want to give them marks out of 10."

According to Mohammed el-Jarh, a Libya analyst and non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Centre's Rafik Hariri Centre for the Middle East, the UN should have stepped in long ago to halt “crimes against humanity and violations of international law.”

“The UN failed to address issues very early on that emboldened those who claim revolutionary legitimacy. Had they tried to reign in Misrata and play an assertive role, this would not have happened.”

Neither Libyan government officials nor the United Nations had responded to MEE’s requests for comment at the time of publication.

In the absence of action from the Libyan government and the UN, Tawerghans are self-organising. They have formed councils to debate proposed solutions; in July 2013, they launched an attempt, shut down by the government, to unilaterally return to Tawergha.

Help is also coming from an unlikely source - Misratans. “A small number of businessmen in Misrata have been helping, giving away food and furniture. But they have to do so in secret; if they helped Tawerghans openly, they would face huge problems in their own community.”

Hope amidst the chaos

Tawerghan attempts to put their struggle on the political agenda have been thwarted by their political disenfranchisement and, increasingly, the chaos that is gripping Libya as a whole. As rival militia groups battle it out for control of the capital, and thousands of families flee the violence, the prospect of a solution seems bleak. However, Mohammed el-Jarh explained that for Tawerghans, the destabilised situation in Libya is not necessarily a bad thing.

“A number of Tawerghans in Tobruk told me that the fact that things are getting worse in Libya is actually positive for them. Now that things are being shaken up, they feel there will be a chance to put their issue back on the agenda in the future.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].