Closing time: How the Turkey currency collapse is hitting small businesses

ISTANBUL, Turkey - Zafer Tulus's family has owned a butcher shop for more than 200 years. Before the modern state of Turkey even existed, the family slaughtered and sold meat.

During the 19th century, Zafer's ancestors ran the business in western Thrace, now in eastern Greece, under the Ottoman Empire. When Turkey lost those lands, the family and the shop moved in 1924 to Kirklareli, in the continental European part of the country. For decades, the shop was passed down the generations, from father to son, until it was given to Zafer.

'Sales decreased, the rent increased, I couldn’t get enough money to hire qualified staff. In the end, I put up the shutters for good'

- Zafer Tulus, butcher

The shop sat in the centre of the small city, next to dozens of other similar small businesses. Tulus described how he called customers he had known for years his "brothers and sisters”. He said he wouldn’t let them leave without offering them a cup of tea.

Then, two months ago, Tulus shut up shop.

“We couldn’t catch up with the new era,” he said over the phone to Middle East Eye. “Sales decreased, the rent increased, I couldn’t get enough money to hire qualified staff. In the end, I put up the shutters for good.”

Tulus detailed the economics that made his business unprofitable.

“I used to sell 100kg of meat, but eventually I started to sell 10kg in the same period of time. That’s because the price of the animals increased dramatically, and the price of one kilogramme of meat went up to 40 lira ($7.5). It was eight lira in 2006. You do the math.”

Zafer also resented big business enjoying backing from the government while smaller businesses like his are allowed to wither and die.

“The big shops and chains enjoy the state support, they can buy the meat for a better price. When we have to sell it for 40 lira, they could decrease the price even to 25 lira."

But for the descendent of butchers, price increases continued to take their toll. “Now I have to say goodbye to Butcher Zafer, 200 years of tradition.”

The lira falls - and falls

Tulus’s small butcher shop is not the only business to close. Across the towns, cities and villages of Turkey, family-run stores are shutting down. The reasons are manifold.

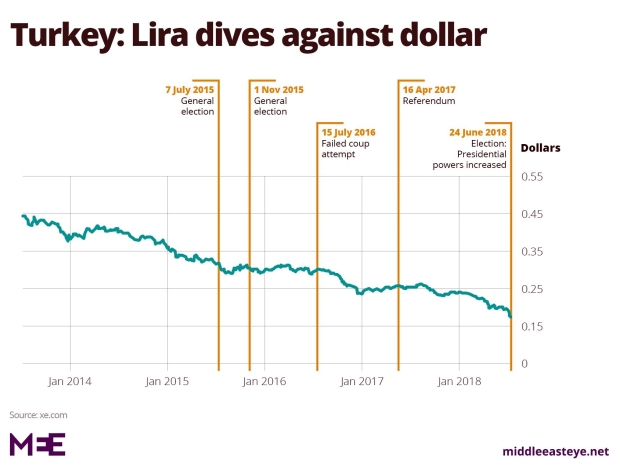

The lira has lost 35 percent of its value since the beginning of 2018 against the US dollar: on Monday, one dollar was worth 5.3 lira. The fall has been especially steep during the past two weeks, amid the diplomatic standoff between Ankara and Washington over the detention of US pastor Andrew Brunson.

'We shifted to a new [political] system and the markets still don’t know how the economy will be managed'

- Burak Saltoglu, professor of economics, Bogazici University

But Burak Saltoglu, a professor of economics at Bogazici University in Istanbul, said that longer term factors have also played their part, including inflation, management of the budget and the current deficit.

There is also the political uncertainty. In the referendum of April 2017, the Turkish people voted to shift from a parliamentary executive to a presidential one. That came into effect with the vote in June 2018, when President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose AKP party has ruled Turkey for the last 16 years, was re-elected.

“We shifted to a new [political] system and the markets still don’t know how the economy will be managed,” said Saltoglu. “So the main reason is uncertainty.”

Saltoglu said that the government lost control of the currency because it prioritised economic growth but was unprepared for some of the side effects, such as the current deficit and inflation rates.

All this has happened against a turbulent background: aside from the referendum and this year's election, there were also two elections in 2015 and the coup attempt of July 2016, as well as repeated diplomatic crises with several countries and terror attacks in Istanbul, Ankara and other towns and cities.“We cannot call this an economic crisis when we look at the growth numbers and unemployment rates. But this is a crisis with the currency," said Saltoglu. "There is a very high risk that the situation will evolve into an economic crisis.”

On Tuesday, the Turkish foreign ministry announced that a delegation of diplomats will visit Washington this week to discuss a solution to these problems.

And on Thursday, it was revealed that Berat Albayrak - finance minister and son-in-law to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan - would be introducing a "new economic model" on Friday which would seek to cool off the economy and address the concerns of investors.

So what will happen next?

Saltoglu said: “We don’t know what foreign policy they [the Turkish government] will follow so it’s not easy to say. I cannot foresee, when I don’t know how the talks are going with the US authorities.

“We need a diplomatic solution to bring relief to the economy. Until there is a resolution on foreign policy, nothing will solve the problems with the Turkish economy.”

Tourists shun gold, want sweets instead

Relief for the economy is something that cannot come fast enough for the jewellers and goldsmiths who trade in the tourist areas of Istanbul. Wander through the Grand Bazaar, one of the world's oldest covered markets, and the talk is of how traders have been badly affected, not least by a rise in the price of gold.

One goldsmith addressed me in English, as if I was a tourist. “I have very beautiful traditional Turkish style jewellery,” he said. “I believe you would love them. Won’t you come take a look at them?”

When I told him that I was not a tourist but actually a Turkish journalist, his face sank.

How is his business going? The truth tumbles out.

Cenk Mutlu, who has owned a small jewellery shop in the Grand Bazaar for decades, has been forced to display signs which read “discount” and “big sale”.

He said that while the increasing cost of gold stops Turks from buying jewellery, the bigger problem is the lack of rich tourists. First they stayed away because of terror attacks; diplomatic crises and the jailing of foreign citizens have only made matters worse.

“We used to sell to European tourists, not the ones coming from Asian countries or the Gulf states. People think they [Gulf tourists] are rich but somehow they don’t buy from us. Since the number of European tourists dramatically decreased during the last three, four years, our situation has been pathetic.”

Another problem has been that most rents in the Grand Bazaar have to be paid in dollars.

“We [the jewellers] are the ones who make the least number of sales in this Grand Bazaar because of the increase in gold prices. Now, we are having difficulty paying our rent. That affects all the economy, since my family cannot go shopping as they did before, we have had to cut our kitchen expenses, etc. The last two years have been the worst since I opened this shop.”

'If our politicians and the people who rule Turkey say: ‘I don’t care about Europe and the US, I don’t care what they say’, then it ruins our relationship and no tourists will come from those countries'

- Muhammed Bozkus, Turkish delight shop owner

In 2016, when the dollar began to rise, the Grand Bazaar said it had decided to accept rent in lira to support the Turkish economy. But the shop owners say that change never came and that they still pay their rent in dollars.

Forty-one of the nearly 600 jewellery stores in the Grand Bazaar have shut since then, often replaced by stores selling Turkish delight instead of gold.

Mohammed Bozkus, a Turkish delight shop owner, says: “After the goldsmith here left two years ago, we realised that Arab and Asian tourists buy only cheap Turkish delight. So we rented this shop and opened this store in 2017.

“We sell more and benefit from the demand. Even if it’s cheap stuff, we can survive. But still, we make less money compared to last year.”

He, like his neighbours, is not hopeful for the future.

“If our politicians and the people who rule Turkey say: ‘I don’t care about Europe and the US, I don’t care what they say’, then it ruins our relationship and no tourists will come from those countries.

“This policy directly affects us. If this policy continues, which seems certain, then I don’t have any hope that business will improve."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].