Babies, films, watches: Turkey’s adoration for fallen hero Omer Halisdemir

ISTANBUL, Turkey – Before Omer Halis Demir was born last year, he was going to be given the first name Ertugrul, a traditional and popular Turkish name which honours the father of the founder of the Ottoman Empire.

But then an event occurred which shook Turkey and the wider world: the failed coup of 15 July.

And so, by the time his second son was born on 27 August, his father Sami was in no doubt: he would be called Omer Halis.

Even then the newborn might still have had a different name - if his father had not managed to persuade his mother. But after Demir explained why, she agreed.

Other expectant parents clearly felt the same: there are now 251 families across Turkey who have used some combination of Omer Halis Demir to name their babies, according to the country’s state-run news agency.

What Omer Halisdemir did

One year ago, Omer Halisdemir was unknown to all but friends and family, a non-commissioned senior sergeant in the Turkish army.

Then the coup attempt happened, an event which rocked Turkish society with profound consequences for the future.

On the night of 15 July, with the Turkish capital Ankara in turmoil, Halisdemir shot dead Brigadier General Semih Terzi, a rebel general trying to take over the special forces command headquarters in Ankara.

Halisdemir was subsequently killed himself - but his action is said to have broken the rebel chain of command and played a vital role in ensuring the coup attempt floundered. The trial of those who shot him began last month in Ankara.

The ingredients for the making of a cult hero are all there:

- A young man from a family of modest means from a town in central Anatolia

- The dashing photos in uniform as he served in the elite special forces unit

- The unwavering commitment to his commander and his country

The appeal is evident to Demir and his family, neither of whom have any fixed political affiliations. “I have always voted for whoever I thought offered the best option," Demir said. "This is my son and we wouldn’t name him for the sake of proving a political point."

'This is my son and we wouldn’t name him for the sake of proving a political point'

- Sami Demir, father

Throughout, Halisdemir’s parents Hasan Huseyin and Fadimeana, who live in the central Anatolian city of Nigde, have kept a low profile. They are reserved and private people who have turned down the state’s offers, both financial and otherwise, since their son’s death. They refuse to divulge their political leanings and those of their late son.

But the cult of Omer Halisdemir has taken hold: Turkish media outlets say the number of babies named after the senior sergeant is not in the hundreds but more than a thousand.

Martyrs, street names and politics

The name "Omer Halisdemir" will not just reverberate around Turkish maternity wards and classrooms for years to come.

Universities, streets, schools, parks and myriad other public spaces and venues have all been renamed to mark the suppression of the coup attempt. Statues have been erected to honour Halisdemir’s memory.

But as political differences emerged so these parties all tried – subtly and otherwise – to claim Halisdemir as being in their camp.

Some observers have even claimed that the Justice and Development Party (AKP), the ruling party, is trying to lay the foundations for a new system - which it allegedly plans to usher in eventually - and is exploiting the failed coup attempt to create legends required to sustain any new system.

These claims arise from long-held fears that the AKP has always had a long-term project to change the secular system in Turkey, introducing gradual changes which are more Islamist in nature. The constitutional referendum on 16 April is seen by such critics as part of that system.

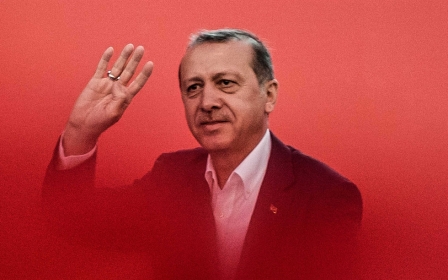

Turkey does, of course, have its heroes. Current President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is arguably the person who has come close to attaining such status in recent times, certainly since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey.

Erdogan’s brash and combative personality, however, has also proven divisive and polarising. The consequence is that he is revered and loathed in equal measure by a populace divided down the middle. When it comes to the martyrs of last summer, the president frequently mentions the heroes and legends, as he terms them, as part of his wider narrative that Turkey is fighting its second war of independence, of which 15 July was one element.

Halisdemir has proved so popular that a planned state-promoted industrial zone for toy production is set to start production of Halisdemir action figures, hoping that toys depicting Turkish national heroes will steer kids away from American fictional icons like Batman and Superman.

A life on film

Mesut Gengec, a documentary filmmaker, was among those deeply scarred by the coup attempt and decided to make a documentary about Halisdemir and his heroics.

His film I, Omer (or Ben Omer in Turkish) won the audience award for best documentary at the International Antalya Film Festival, one of Turkey’s most prestigious cultural events, last October.

Gengec said that although Halisdemir’s name and the mood in the country must surely have helped him win the award, the quality and depth of the film merited it.

“I spoke to so many of Halisdemir’s friends, colleagues and those who knew him. All I wanted to do was create a historical record documenting the actions of a hero,” Gengec told MEE.

Gengec is aware that many people are engaging in opportunism and looking to make a quick buck by exploiting Halisdemir’s name.

“That is why I didn’t release the film for commercial screening," he said. "It is only doing the festival circuit."

But others are less moral then Gengec. Halisdemir’s parents have taken a firm stance against the use of their son’s name for political and commercial purposes.

'All I wanted to do was create a historical record documenting the actions of a hero'

- Mesut Gengec, director

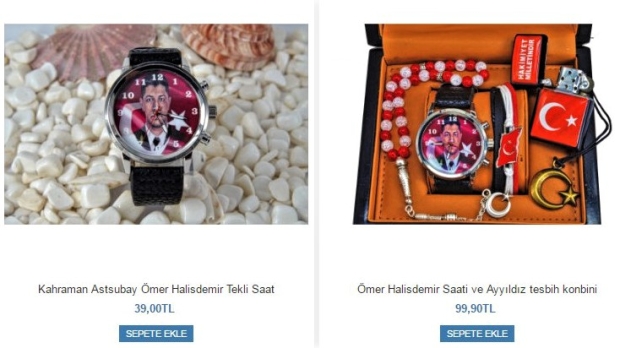

Despite attempts to prohibit commercial trading using his name and image, the robust trade continues unabated: his name and image have been used on everything from watches and fridge magnets to worry beads and coffee mugs.

A website called Nationalists Store in Turkish displays a variety of Omer Halisdemir-branded products, as does another called the Grey Wolves Basket, named after the right-wing Nationalist Movement Party’s grassroots movement.

The last straw for Halisdemir’s parents came late last year when a housing project in the province of Sakarya started advertising a development named after their son and promising the ultimate in a comfortable lifestyle.

Halisdemir’s family has vowed legal action against anyone using their son’s name or image for commercial products and purposes. But the wider trade still continues unabated.

'Raise that lion heart well'

Demir disapproves of the commercialisiation and draws a distinct line between such ventures and the naming of his son.

"I don’t think any of it can make any less of Omer’s heroic deeds and his place in our country’s history.”

“We wanted to make Omer Halisdemir’s memory live on, and naming our child after him was the greatest thank you we could say to him," he said.

Demir told MEE that Halisdemir’s parents in the central Anatolian city of Nigde had been informed of the naming of his son after theirs by some of his colleagues travelling to the city on business and they had appreciated it.

“My colleagues told me that they said: ‘Tell them to raise that lion heart well and make all of us proud'."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].