Turkish newspaper with policemen ‘playing editor’

Mustafa Edib has been working as a journalist for years and prides himself on fighting for the rights of the marginalised.

In 2009, he publicly defended President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) when it faced a closure trial for alleged violation of the state’s secular principles. He has no regrets about helping to preserve a political force that would one day snub out his own voice, “because back then, AKP was being oppressed, and we stand against all types of tyranny”.

Like other journalists in Turkey, he now fears that his career in his home country may be finished.

On 4 March, Turkey's bestselling newspaper, Zaman, where Edib had worked for seven years, was raided by police that seized control of its operations and installed a new board of trustees appointed by the courts and believed loyal to the AKP government.

The paper is affiliated with the government's former ally-turned-adversary, Fetullah Gulen, and stands accused of having links with “terrorist” groups. So far, the government hasn’t released any substantial details about the on-going investigation, but the closure of numerous other media outlets has raised concerns about a wider political crackdown on media freedoms.

When Edib, the newspaper’s foreign editor, showed up to work on the morning after the seizure, his office resembled a police barracks. He told Middle East Eye that the Internet connection had been disabled and the paper was already prepared, but that he “didn't know where or by whom, quite frankly”.

He still goes to work each day, but said that each time he goes out for a cigarette or to take a phone call, he isn’t sure if he’ll be allowed back in.

While this hasn’t stopped him from speaking out about the closure, his newspaper has been forced to make a 180-degree turn in its editorial tone, as it has begun publishing pro-government stories.

The next day, employees were given access to some computers and told to prepare the pages. However, “they weren’t sent to the printing press as we had entrusted them in to the hands of the court-appointed trustees,” Edib said.

Reporter Zeynep Karatas said she was shocked when her story about police brutality during Women's Day demonstrations was replaced by an article about the inauguration of a new bridge.

Within six days of the takeover, Zaman’s circulation numbers fell from 600,000 to - yes - 18. This has been a bittersweet victory for Edib, who views the boycott by readers as a show of solidarity and passive resistance. Yet the newspaper he loves is being strangled before his eyes.

Employees wonder why they are putting together a newspaper that is never going to print and is expected to be read by only 18 people. In spite of this, many of them are refusing to abandon ship.

“I don’t want to give them the pleasure of resigning,” said Sevgi Akarcesme, the newspaper's editor-in-chief, in an interview for Politico. “I am waiting for them to fire me.”

Police are 'playing editor'

Zaman's journalists are working under heavy police surveillance.

“There must be at least 30 to 40 policemen inside our headquarters in Istanbul who are playing 'editor,'” Edib said.

“They’re patrolling the building and monitoring our every move. When a group of five or six colleagues gather around, it is only a matter of time before one or more police officers starts asking questions about what they are discussing.

“I was giving an interview to a Singapore-based TV channel in a public park next to the building and a policeman approached me, took my name and told his superiors I was talking to foreign media,” he said.

Despite their resistance, the employees are helpless against the new board of trustees. On Thursday, the new administration deleted the paper's digital archives, removing thousands of articles, including those of Haaretz reporter Louis Fishman.

The government has rejected criticism, claiming that the takeover is legal rather than political, and that the majority of Turkish media remains untouched despite its critical stance against the government.

"It is out of the question for either me or any of my colleagues to interfere in this process," Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said.

Edib disagrees. He said the deletion of Zaman’s archives was a political move to damage the paper's legacy and remove all traces of critical opinion from its records.

“Every day there has been a new Zaman on the shelves, but I feel no part in it, nor do any of my colleagues, since we have nothing to do with the editorial line, story choice or layout,” he said.

Those were his last words before our telephone conversation was interrupted by a police officer.

The trustee media

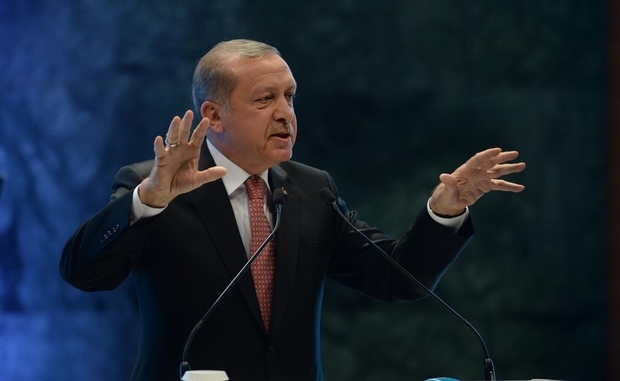

Lack of press freedom in Turkey is an issue in its own right, but the government's collusion with the judiciary in seizing media outlets and jailing journalists signals even bigger problems, according to critics of Erdogan.

According to Aykan Erdemir, a former member of Turkish Parliament now serving as a senior fellow at the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies, the evolution of Erdogan's “disciplinary technologies” paints a startling picture of media control in Turkey.

In 2009, Erdogan first raised concerns when he used a whopping $2.5bn punitive fine against the Dogan Media Group for alleged tax irregularities. At the time, the former OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, Miklos Haraszti noted in a letter to Davutoglu that the fine was disproportionate.

“Were the holding to pay these fines, the Dogan Media Group claims that they would go bankrupt. This could significantly weaken media pluralism in Turkey," he said.

Last November, Erdem Gul, the Cumhuriyet newspaper's Ankara bureau chief, was detained for three months along with his editor-in-chief, Can Dundar, on charges of revealing state secrets and “aiding a terrorist organisation,” when the pair alleged in a report that Turkey was supplying arms to Islamists in Syria.

Gul and Dundar were acquitted by a constitutional court, but Erdogan has refused to accept the decision.

“Erdogan's control over the media cannot be explained just by the fight between him and Fethullah Gulen. This is a bigger issue,” Gul said. He has concerns about how far Erdogan might go in order to silence opposition in the run-up to a referendum on the presidential system. “Voices, that express discomfort [regarding Erdogan's presidential model], even within his own party, are being smeared and silenced.”

In this climate, Aykan said he wouldn’t be surprised if the remaining independent media outlets begin to “willingly” promote the virtues of Erdogan’s executive presidential system.

The EU and refugees

Zaman reporter Zeynep said she was officially fired, ostensibly for her activity on social media.

Edib said that it is a matter of time before he also faces dismissal. He has been busy tweeting photos of his ordeal, talking to foreign journalists and provoking the ire of his new bosses, but he feels a lack of solidarity from Turkish journalists and the international community as well.

Two days after the newspaper takeover, the Turkish government was greeted in Brussels with promises of billions in aid and renewed prospects of joining the EU for the country's help in resolving Europe’s migrant crisis, which critics say indicates the relative weakness of the EU's negotiating power.

Edib and Akarcesme said they felt disappointed, if not betrayed, by the EU appeasing Turkey in exchange for cooperation in curbing Syrian refugees. Brussels is only validating Erdogan's image, power and popularity at home, they said.

Despite this, Edib said he feels defiant. He doesn’t know how long he’ll last at his job but he has a plan. For now, he said, he’s busy jumping back and forth over the proverbial red line, just enough to keep his position and use it to rally people to his cause.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].