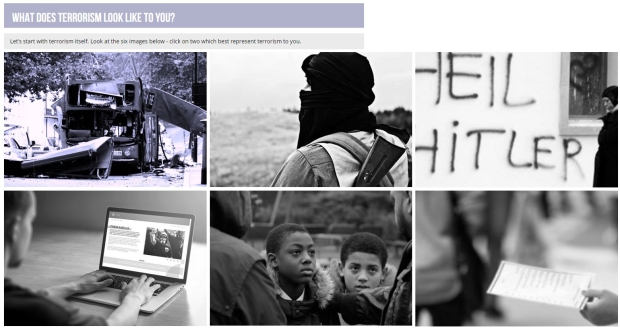

Prevent courses on sale to schools deemed 'poor quality' by UK government

More than 20 training courses marketed to teachers and other public sector workers to help them identify potential terrorists were rejected by the UK’s Home Office for inclusion in a Prevent training catalogue, Middle East Eye has discovered.

Growing evidence of a lack of quality training courses for the anti-radicalisation programme - which has been rolled out to half a million frontline public sector workers - includes claims that some staff have been accredited to deliver Prevent workshops with as little as two hours training.

However the Home Office said it would not reveal the names of the products, some of which it deemed to be poor quality, or the organisations behind them because it would prejudice the commercial interests of the companies concerned.

The catalogue, which was published in March, was produced by the Home Office as guidance for public institutions following the introduction last year of the Prevent Duty, which requires teachers, doctors and other staff to have “due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism”.

The duty also requires public sector authorities to provide “appropriate training” for staff to help them recognise signs of radicalisation.

Prevent is a strand of the UK government's counter-terrorism strategy concerned with tackling extremism with the aim of “stopping people becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism”.

But it has been widely criticised, with parliament's Home Affairs Select Committee last month adding its weight to calls for the strategy to be reviewed amid widespread complaints that it is misguided, counter-productive and discriminatory against Muslims.

One of the main points of criticism raised in the select committee's report was the inadequacy of Prevent-related training currently available to teachers and other public sector professionals.

“We are concerned about a lack of sufficient and appropriate training in an area that is complex and unfamiliar to many education and other professionals, compounded by a lack of clarity about what is required of them,” it said.

The Home Office catalogue includes government-produced training material such as the Workshop to Raise Awareness of Prevent (WRAP), a one-hour session delivered by a Home Office-accredited trainer, and Prevent E-Learning, a 45-minute online training course.

It also promotes 19 other courses and workshops offered by police forces and other public bodies, by charities and by private companies. Some are free to access while others quote potential costs running into thousands of pounds.

Responding to a Freedom of Information request from MEE, the Home Office confirmed that 24 products considered for inclusion in the catalogue had failed to meet its selection criteria.

These required products to be “broadly consistent with Prevent policy”, to “use appropriate language”, to be “broadly effective” and to “support frontline staff in increasing their understanding, knowledge and awareness” of the Prevent Duty.

“Reasons for non-inclusion included products not being publicly accessible, or the target audience of the product not being practitioners with responsibilities under the Prevent Duty, courses being of a poor quality or simply repeating information already within the statutory guidance,” the Home Office said.

But the Home Office said that releasing the names of the organisations or products was not in the public interest.

“Releasing the identities of organisations and products that were not included within the Prevent Training Catalogue may lead to misunderstandings around the capability of these organisations, leading to loss of reputation affecting commercial interests,” it said.

It added that naming the organisations and products that had been rejected could affect their impact if included in future iterations of the catalogue.

“Teachers are concerned that there is a market opening up in training courses relating to all aspects of education”

Ros McNeil, National Union of Teachers

Open market

But the commercial availability of so many courses rejected by the Home Office raises further questions about the quality and consistency of Prevent training being offered to public sector workers.

Ros McNeil, the head of education at the National Union of Teachers, which has opposed the introduction of the Prevent Duty in schools, told MEE that the quality of Prevent-related training material was among its members' main concerns.

“Teachers are concerned that there is a market opening up in training courses relating to all aspects of education,” she said.

“The government does need to do more to quality assure what is being used and to come up with a strategy to ensure that schools can't access and don't access materials that are substandard and might be misleading and which, at worse, might fuel uncomfortable stereotypes about Muslim young people.”

A recent report by Rights Watch (UK), a human rights organisation, on the impact of Prevent in schools also cited complaints by teachers about a lack of appropriate training.

“The training provided to public sector workers to carry out the Prevent Duty is woefully inadequate. Almost all the workers that we spoke with felt ill equipped to detect signs of radicalisation,” Yasmine Ahmed, director of Rights Watch (UK), told MEE.

Other education sector professionals have also raised questions about the quality and implementation of Prevent training. In a report in July, Ofsted, the schools inspection body, said staff training had been ineffective in a third of further education colleges visited.

The National Association of Head Teachers has also described training as a “key concern”, despite describing itself as “broadly supportive” of the Prevent Duty.

“We know that the most reliable source of training is the WRAP training delivered by police forces, but members are reporting to us that this is becoming difficult to find,” it said in evidence submitted to the Home Affairs Select Committee.

“This leaves our members in a precarious position of trying to secure training on the implications of a duty that they do not understand well at that stage, on the open market... This is an emerging area of expertise for schools and they need to be able to rely on accredited training that has been certified by the police or the Home Office as fit for purpose.”

550,000 frontline workers trained

A spokesperson for the Home Office told MEE that more than 550,000 frontline public sector workers had received training since 2011 in spotting the signs of radicalisation and said the government's own survey of school leaders suggested that more than 80 percent of them were confident about implementing the Prevent Duty.

The spokesperson also said that schools were capable of determining the nature and level of training they required to meet their Prevent Duty responsibilities.

But in Scotland, Richard Haley, chair of Scotland Against Criminalising Communities (SACC), a civil liberties campaign group, told MEE that many schools were actively sourcing alternatives to the Home Office's WRAP training because of concerns about Prevent.

“There has been a general opposition, or at least lack of enthusiasm, towards Prevent in Scotland which only now is beginning to be rolled out in the public sector,” said Haley.

Because of that, he said many schools were using alternative training packages or embedding Prevent-related material within broader safeguarding staff training.

"All they're doing is ventriloquising the government guidance"

Bill Bolloten, Education Not Surveillance

“In a way, that is good because it is a reflection of the opposition to Prevent that there has been. But there are real problems with it because, even though the whole framework and thinking and vocabulary of Prevent is flawed, what we are seeing is the sloppy and inaccurate presentation of already flawed material.”

Trainers trained in two hours

Questions have also been raised about the quality of the Home Office's own training material with notices for courses posted online indicating that some trainers tasked with delivering its WRAP workshops may have been accredited to do so after receiving just two hours of training themselves.

“All they're doing is ventriloquising the government guidance. They are just reprinting information on slides and using a very narrow body of training material,” Bill Bolloten of the Education Not Surveillance campaign network told MEE.

“We know that even in official bodies there is disquiet about the problem of training not equipping practitioners well enough. But this is hardly surprising because the government is saying itself that with two hours training you are considered to have sufficient expertise and confidence to develop courses and deliver training on complex issues.

“It is not credible and it is potentially harmful. Would they consider two hours sufficient for someone to set themselves up as experts on the risks of gang activity or child sexual exploitation?”

The Home Office told MEE that more than 2,700 people were accredited to deliver WRAP workshops, which it described as its “core training product”.

Most of those had a background in safeguarding vulnerable individuals, and there were additional training resources available to facilitators once they were accredited, it said.

There had also been 44 percent increase in the uptake of WRAP training in the first six months of the 2015-16 financial year, with 59,218 people taking the course compared with 41,255 in the previous six months.

“Prevent is working,” the Home Office spokesperson said. “We have seen all too tragically the devastating impact radicalisation can have on individuals, families and our communities, and protecting those who are vulnerable and at risk is a job for all of us.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].