REVEALED: Juvenile prisoners and mentally ill killed in Saudi executions

Prisoners arrested when they were children and others suffering from mental illness were among dozens of inmates recently executed in Saudi Arabia, exclusive sources in the kingdom have told Middle East Eye.

On 2 January Saudi Arabia announced it had executed 47 prisoners convicted on charges of terrorism, among them the influential Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, who led anti-government protests in the Eastern Province before his arrest in July 2012.

Nimr’s execution sparked protests at home and abroad, including in Iran, where protesters ransacked the Saudi embassy, leading to Riyadh severing ties with Tehran and plunging the two regional rivals into a diplomatic crisis.

But little has been reported about the 46 other prisoners who were executed in 12 cities across the kingdom.

Four were Saudis from the Eastern Province - including Nimr. The other 43 were accused of having links to al-Qaeda, and some were convicted of either carrying out, planning, or supporting attacks in the kingdom between 2003 and 2006.

Four of the 43 were convicted of banditry, a crime that is punished in Saudi Arabia by having alternate limbs cut off on opposite sides of the body, followed by beheading and the display of the corpse.

Saudi authorities have not disclosed how the prisoners were executed but a security source who guarded a Riyadh execution site told Middle East Eye about the scene when the killings took place on 1 January, a day before the official announcement.

“It was a massacre. There was blood and body parts everywhere,” the source said, adding that the executions did not take place inside a prison but were carried out at a private location in the capital.

The source could not confirm how many people were killed in Riyadh but said the executions began in the morning and did not finish until the afternoon.

The bodies were not returned to the prisoners’ families and were instead buried in a secret location by Saudi authorities.

While Saudi authorities released a full list of names for the prisoners who were executed, only two of the al-Qaeda prisoners have been profiled in the media.

One is Faris al-Shuwail, who was accused by Saudi Arabia of being a leading ideologue for the group. The other is Adel al-Dhubaiti, who was convicted of killing BBC cameraman Simon Cumbers and seriously injuring BBC journalist Frank Gardner during a 2004 shooting in Riyadh.

Untold stories of executed juvenile prisoners

Middle East Eye can reveal that one of those executed was Mustafa Abkar from Chad. He was one of two foreigners among the 47, the other being an Egyptian named as Mohammed Fathi Abula'ti Al-Sayed.

Abkar was 13 years old when Saudi security forces arrested him in Mecca on 19 June 2003, according to a source familiar with his case.

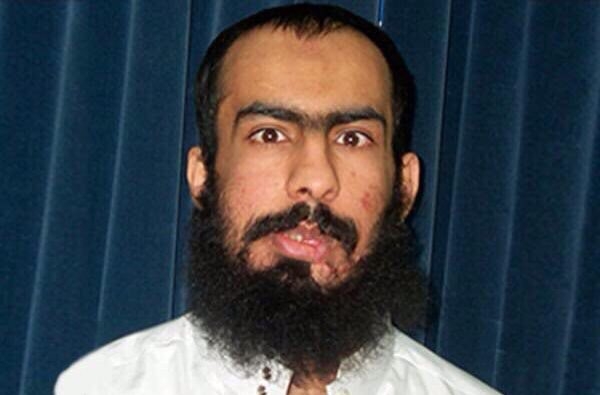

Abkar was featured in a documentary on young al-Qaeda members aired by the Saudi-owned channel Al Arabiya in December last year.

In the programme Abkar was pictured as above, although not named, as having been one of three boys from Chad who had lied to their parents and travelled to Saudi Arabia to attend a week-long Quran training course in 2003.

The documentary said the Quran training programme had “turned out to be a terrorist criminal course” and that the Chadians were arrested in a police raid.

Abkar was arrested at a time of heightened concern in Saudi Arabia about Al-Qaeda. On 12 May 2003 the group carried out a string of bombings on three compounds housing Westerners in Riyadh, killing 39 and injuring more than 160 others.

In the documentary, security forces said the young Chadians expected to be released quickly.

“They were young in age,” an officer told interviewers. “Those we caught expected the matter would end quickly and that they could go back to their families.”

It is not known what happened to the other three boys, but Abkar was never released. Little is known about his time in prison or any trial he may have faced, but the source familiar with his case said he only appeared in court once, and that was when he was sentenced to death on 14 October 2014 - more than 11 years after he was initially arrested.

“He had no lawyer. No one asked anything about him. It’s really sad that he has been beheaded without anyone knowing anything about him,” the source said on condition of anonymity.

International rights groups have raised the cases of other juvenile prisoners on death row in Saudi Arabia to some success.

Reprieve, which campaigns against the death penalty, has called on Saudi authorities to stop the executions of Ali al-Nimr, the nephew of Sheikh Nimr, Dawoud al-Marhoon, and Abdullah al-Zaher, all of whom were arrested in the Eastern Province when they were under 18.

While the three have not been freed, they were not executed on 1 January as had been expected. Middle East Eye has reported that international pressure led to Saudi authorities reassuring international allies that they would not execute Nimr, Marhoon, and Zaher.

However, the case of Chadian Abkar has only been revealed after his execution and he received no international attention.

“Nothing has been published about him,” Yahya Assiri, head of the Saudi human rights organisation Al Qst, told Middle East Eye from London. “His case was completely secret.”

Abkar wasn’t the only prisoner executed on 1 January who was a juvenile when they were arrested.

Mishaal al-Farraj was 17 when he was arrested in the Malik area of Riyadh in June 2004.

Farraj had joined al-Qaeda after his father Hammoud was killed in January 2004 in a raid by security forces to arrest one of his other sons - Khaled - who was believed to have been part of a cell planning attacks in the kingdom.

A report by the Saudi ministry of interior at the time said that Hammoud al-Farraj had previously co-operated with security forces and would be acknowledged for this posthumously.

However, his son Mishaal was left angry by his father's death and joined al-Qaeda to seek revenge against authorities. When he was arrested it was reported that he had been picked out to be a suicide bomber by al-Qaeda and was being trained in surveillance and reconnaissance.

The source familiar with the cases of Chadian Abkar and that of Farraj said Farraj was tortured in prison and held for years without ever being taken to court, as well as being denied access to legal representation.

Saudi activist Assiri claimed that many of the 47 executed prisoners had been mistreated during their imprisonment.

"A number of them were severely tortured and only brought to trial after years of physical and psychological torture," he said.

"The authorities forced them to confess under duress to activities we cannot confirm actually took place. When a defendant informed the judge they had been subjected to torture, the court would send them back for interrogation and further torture before hearing the confessions again."

Officials at the Saudi embassy in London did not respond to requests for comment, but authorities have defended the executions as being the product of “completely transparent” trials carried out “in line with Islamic law”.

The crucifixion of a mentally ill inmate

Other prisoners who were executed on 1 January include people who were suffering from mental illnesses.

One of them was Abdulaziz al-Toaili’e, an al-Qaeda leader and former writer for the group’s magazine Voice of Jihad. He was arrested in 2005 after being shot in the face by security forces east of Riyadh.

Toaili’e was a religious scholar who had issued fatwas endorsing the 2003 Riyadh compound attacks.

In prison Toaili’e is said to have become severely mentally unwell – Saudi activist Assiri claims this was as a result of prolonged physical and psychological torture.

Toaili’e’s poor mental state was first reported by his cellmate, the former judge turned human rights activist Suliman al-Reshoudi, who was sentenced to a 15-year prison sentence in 2011 for "breaking allegiance with the king".

Reshoudi, who is now 79, shared a prison cell with Toaili'e in 2012 at al-Ha'ir political prison, south of Riyadh.

Reshoudi has told fellow activists including Assiri that Toaili’e would speak to insects, run around naked screaming, and consumed his own bodily waste.

Toaili’e regularly attacked Reshoudi and called him a non-Muslim for believing in democracy. Reshoudi claims Toaili'e said he had stopped praying because he was “very close to Allah”.

In 2012 Reshoudi wrote to the Ministry of Interior and requested Toaili’e be released so he could receive treatment for what he believed was severe mental illness.

Assiri, a friend of Reshoudi who is familiar with the case, said: “It was very clear he (Toaili'e) was mentally unwell – in a very serious way.”

In 2014 Assiri said he sent a letter to the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights explaining that Toaili’e was having mental health problems and had been sentenced to death.

He received no reply. The UN did not respond to requests for comment at the time of publication.

Toaili'e was convicted of banditry and on 1 January would have had his limbs cut off before being beheaded.

Prisoners needed to be 'dealt with'

Analysts have grappled with the reasons behind the timing of the mass execution on 1 January.

Prominent Saudi columnist Jamal Khashoggi told Middle East Eye on the day of the killings that the Saudi public had been wondering why it had taken so long to execute the prisoners convicted in relation to al-Qaeda.

"Those criminals did act brutally against innocent civilians [and] they needed to be dealt with, so what happened is, I'm sure, very much welcomed by most Saudis," he said.

Rights groups responded with fury to the executions and pleaded with Riyadh to end its capital punishment.

“It is a bloody day when the Saudi Arabian authorities execute 47 people, some of whom were clearly sentenced to death after grossly unfair trials," Amnesty International Middle East director Philip Luther said on 2 January in a statement.

"Carrying out a death sentence when there are serious questions about the fairness of the trial is a monstrous and irreversible injustice. The Saudi Arabian authorities must heed the growing chorus of international criticism and put an end to their execution spree."

Saudi authorities have continued to defend the executions. In an exclusive interview with the Economist, Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman contradicted activist claims of mistreatment and said his country's judiciary had safeguarded prisoner rights.

He said those executed "were sentenced in a court of law with charges related to terrorism and they went through three layers of judicial proceedings. They had the right to hire an attorney and they had attorneys present throughout each layer of the proceedings. The court doors were also open for any media people and journalists, and all the proceedings and the judicial texts were made public."

Executions in Saudi Arabia have risen sharply since Prince Mohammed's father King Salman ascended to the throne in January last year. In 2015 at least 157 people were executed, the highest total since 192 people were put to death in 1995.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].