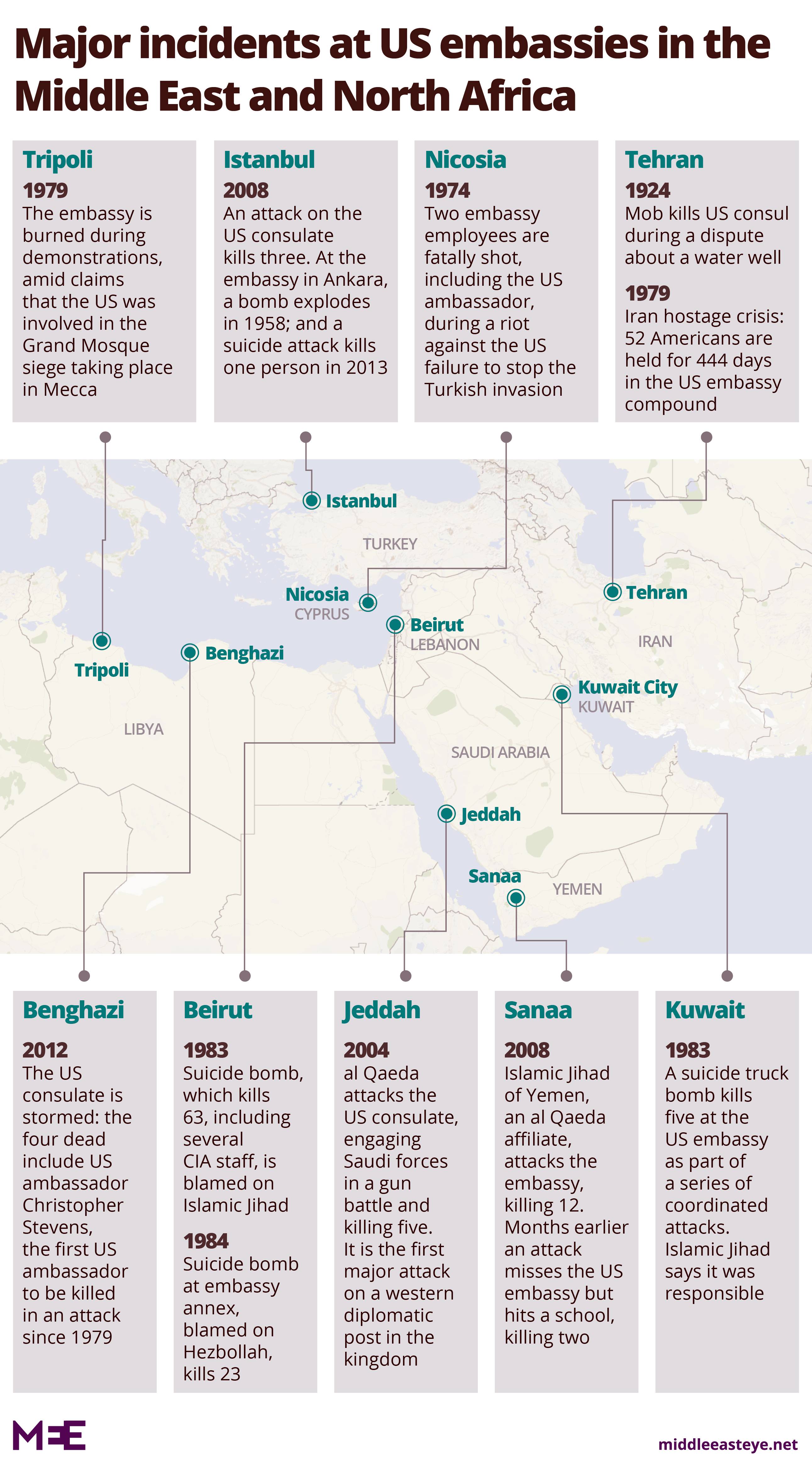

Explained: How attacks on US embassies have shaped America’s future

US policy in the Middle East, North Africa and beyond has often been swayed by how American embassies and missions are targeted across the region.

Protests outside the US embassy in Baghdad are core to the current confrontation between Iran and Washington, which has plunged the region into fresh crisis.

On 31 December, hundreds of Iraqis encircled and vandalised the embassy compound, outraged by US air raids in Iraq and Syria that killed 25 Hashd al-Shaabi fighters during the previous weekend.

That precipitated the US assassination on January 3 of Qassem Soleimani, Iran's top general and head of the Quds force, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard's overseas arm.

American diplomatic missions, as US representatives of the country abroad, can become lightning rods for anti-US sentiment, sometimes resulting in death and destruction.

In 2018, Donald Trump’s decision to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem alienated important partners in the region, sparking Palestinian protests on the frontier between Gaza and Israel, with fatal consequences.

The reverberations are not just felt on a regional level - often, American prestige and policy suffer as well, with high-flying political careers back in Washington destroyed amid the fallout.

Tehran 1924: Lynching heralds martial law

Any discussion of US diplomacy and Iran triggers recollections of the 1979 crisis and the Islamic Revolution. Yet US diplomats had fallen victim to events in the region long before Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini rose to power.

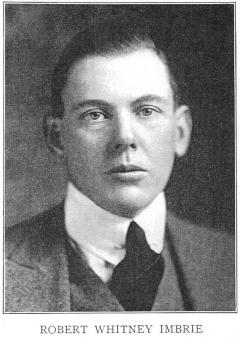

In 1924, Robert Whitney Imbrie, a major in the US army, was the American vice consul in Tehran. A spy-adventurer, his pre-foreign service exploits included successfully bringing a live gorilla from the Congo to New York and volunteering for the French army’s ambulance service during World War One.

Before taking his position at the US embassy in Iran, Imbrie gained a reputation as a hot-headed, fearless and vehemently anti-Bolshevik American agent, once using his walking stick to beat the head of the Soviet secret police department in Petrograd.

Ironically, Imbrie spent much of his working life undermining what he regarded as godless Soviets – but it was religious fanatics who were to determine his fate.

In July of that year he took a carriage to inspect an angry crowd of anti-Bahai protesters in the centre of Tehran. The protesters were gathered around a well that was rumoured to have miraculous healing powers. But now the Bahais, a religious minority, had been accused of poisoning the font. Imbrie approached, carrying a camera to take photographs for the National Geographic Society and accompanied by his bodyguard, a burly oilfield worker. But soon he drew attention from the crowd, some of who accused him of being a Bahai.

He was attacked, badly beaten and rushed to a nearby hospital, where the mob then forced their way into the operating theatre and killed him.

Understandably, Imbrie’s death was a source of tension between Tehran and Washington, which demanded justice. Eventually a soldier and two teenagers were found, accused and executed.

The incident also cast doubt on the safety of foreigners in Iran, as US newspapers fretted about security and religious fanaticism in the region.

The New York Times wrote that Iranian authorities should “cease to resort to appeals to the fanatical instincts which permeate not only the mob but also a large proportion of the intelligentsia” and urged Tehran to better protect foreigners in future. This it did, when Iranian Prime Minister Reza Khan declared marital law, using the crisis to consolidate his power before eventually assuming the Iranian throne.

WAK Fraser, British military attache at the time, noted how “the event gave him … the excuse for declaring marital law and a censorship of the press... Numerous arrests have been made, chiefly political opponents of the prime minister.”

Imbrie was buried with full honours in Arlington National Cemetery. But his death had opened a new chapter in Iranian politics.

Tehran 1979: Hostages and revolution

Fifty-five years later, a second crisis involving American diplomats heralded another significant shift in US-Iranian relations.

In early 1979, the US embassy in Tehran was a long, two-storey redbrick building standing on an avenue in central Tehran, the scene of intense US-Iranian cooperation which neither government expected to be broken.

Popularly likened to an American high school in appearance, the mission was known as “Henderson High”, a reference to Loy Henderson, its first US ambassador.

“It was like any other embassy, except the relationship of the United States and Iran was very close,” says Iranian-American historian Shaul Bakhash at George Mason University in Virginia.

“The shah worked closely with the Americans on diplomatic issues, on regional security, on the sharing of intelligence.”

But all that changed in February 1979, when Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the shah of Iran and son of Reza Khan, was deposed by the Islamic Revolution.

At first Washington managed to uphold an uneasy relationship with the new Iranian government, despite the revolutionary fervour in Tehran. But when the US granted Reza Shah asylum in May of that year, the hardliners had all the reason they needed to target the embassy.

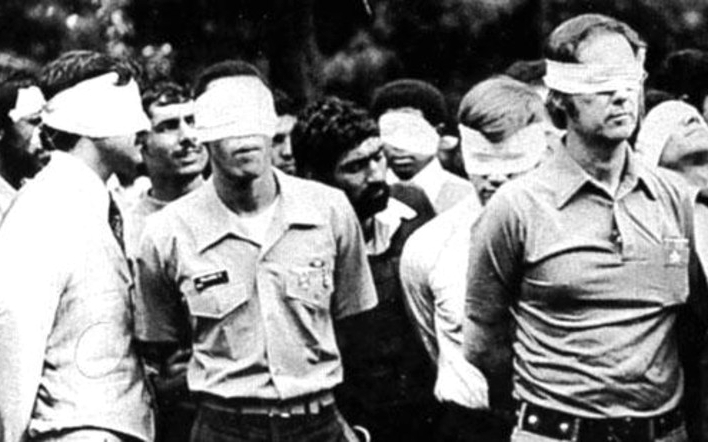

A group of students stormed the building on 4 November, taking 52 American diplomats and citizens hostage and parading them blindfolded and bound in front of television cameras.

“I was in Iran at the time and I must say the images were electrifying,” Bakhash said. “It was a precise, planned political move that was designed to drive a wedge between the Iranian and American governments.”

The hostage crisis, which lasted 444 days, was the death of President Jimmy Carter’s administration. His downfall was fuelled by the failure of Operation Eagle Claw, an unsuccessful attempt to rescue the hostages in April 1980, which resulted in the deaths of eight US service personnel in the desert southeast of Tehran.

The release of the hostages in January 1981 was regarded as an early victory for Carter's successor Ronald Reagan, who was sworn in as president just minutes before they were freed.

But the crisis was catastrophic for US-Iranian relations, which have never recovered and are currently at a new low following the rejection by US President Donald Trump of the Iran nuclear deal.

Today the Tehran embassy - popularly known as the “den of espionage” in Iran - is a museum, standing as a monument to a shattered relationship. Murals and posters criticising American and Israeli “arrogance” cover the walls, while various encryption devices and communication equipment are displayed behind glass screens, proof the Iranians say of Washington’s meddling overseas.

“For the Iranians it showed that the United States could be beaten,” says Bakhash.

Beirut 1983: Bombed into retrenchment

In early 1983, the US embassy in Lebanon was nothing if not picturesque, nestled as it was next to the American University of Beirut’s leafy campus and boasting vistas of the Mediterranean.

Journalist Kai Bird, who lived in the mission as a child, says: “The Beirut embassy was right on the corniche, a lovely venue. Any Lebanese, any American could just walk right into the embassy, say hello to the marine guards, state their business and get an appointment to see somebody.”

Such openness in 2018 is unimaginable, as a visit to any US mission across the world will prove, in part due to the devastating suicide bombing in Beirut that took 63 lives and changed the American diplomacy forever.

In April 1983, Lebanon was eight years into a bloody civil war, which would eventually leave an estimated 150,000 dead and not end till 1990.

On the 18th of that month, a truck loaded with explosives drove into the US embassy and detonated. Packing more that 900 kg of explosives, the truck bomb tore apart the embassy's entire facade, as the explosion shattered windows across west Beirut. Seventeen Americans, 32 Lebanese employees of the embassy and 14 passersby and visitors were killed, including some of the CIA's top agents.

It was to be the opening salvo in a new type of warfare with which the United States still battles today. Likely directed by Iranian intelligence, the attack was carried out by Islamic Jihad, a militant group that later grew into Hezbollah.

It was also the first of several attacks on the US in the city. In October 1983, two truck bombs targeted at an international peacekeeping force killed more than 300 people, including 241 US peacekeepers. And in September 1984, 24 people were killed by a car bomb attack on the US embassy annex in east Beirut.

The attacks drew strong rhetoric and promises to see the mission through from then-US President Reagan. But by February 1984 the American military presence in Lebanon began to be drawn down, with the British, French and Italian forces following suit.

Bird, whose book The Good Spy: The Life and Death of Robert Ames profiles a CIA operative who was killed in the 1983 attack, says the assault on the US embassy was a turning point.

"There’d never been a military-scale attack on a US embassy before and I think it inaugurated a new form of warfare. It changed the whole landscape of US diplomacy - literally the architecture changed.”

In an attempt to avoid a repetition of such a disaster, US embassies and missions worldwide now sit behind layer upon layer of security.

Many invariably resemble fortresses, set in isolated locations and sat behind thick walls, high fences and dozens of cameras. The former US embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square, for example, was constructed during the 1950s. Security increased over the decades, until the area on one side of the residential square was cordoned off. The new embassy, in Vauxhall, opened in December 2017, is on open ground and surrounded by a semi-moat.

But such security has its disadvantages. “Since 1983, the average diplomat is extremely isolated, and it’s very hard for them to develop friendships and contacts with local journalists,” says Bird

“So that’s had a very real impact on the daily routine and life of the average American diplomat. It’s terrible and it sends completely the wrong message. It sends a message to the average person in Lebanon or Egypt or Nepal or India that you can’t approach America, that we Americans are fearful.”

Benghazi 2012: The lingering legacy

Missions in Tripoli, Kuwait City, Jeddah, Damascus, Sanaa, Istanbul, Cairo and Tunis have all witnessed bombs, assaults or riots. A suicide bombing in Ankara in 2013, which killed one person, is just one of the more recent examples.

But none has had quite the political reverberations in recent years as the attack on the US temporary mission facility in Benghazi on 11 September 2012, which killed Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans.

In 2012, Libya was emerging as splintered and unstable country after the uprising and NATO operation that toppled long-time leader Muammar Gaddafi the previous year.

Benghazi had been the cradle of the revolution against Gaddafi’s regime. Stevens was in the city promoting democracy and American friendship, as the US considered making its presence in the eastern Libyan city permanent. It was to cost him his life.

On the 11th anniversary of the attack on the World Trade Center, the militant group Ansar al-Sharia staged an assault on the US mission. Coming at the compound from all angles, the militants broke through the security using heavy weapons, RPGs and grenades. Once inside, the assailants started a fire, filling the Americans' hiding place with smoke. Stevens managed to escape the building and was taken to a nearby hospital, but eventually died of smoke inhalation.

The unexpected attack and the diplomat’s death shocked America: according to David Des Roches at the National Defense University, it was also a wakeup call for US policy in Libya.

“It showed that the country had descended into something that was sub-national,” says Des Roches. “Right now, when people look at Libya, it’s basically divided along the lines the Emperor Constantine divided it at the time of the Roman Empire.”

But Benghazi’s more enduring legacy was, perhaps, seen not in Libya but 8,000 km away in the White House.

The attack sparked a lengthy inquiry, and exposed then-secretary of state Hillary Clinton’s use of an external email server – a scandal that plagued her 2016 run for the presidency.

“In her memoirs secretary Clinton attributes her defeat to the fact that additional emails were unearthed just five days before the election," says Des Roches. "Well, we only found out that those emails existed because of the inquiries into Benghazi.

“So if you take Secretary Clinton’s analysis, if not for Benghazi [then] she would be president today.”

Going by the same logic, Donald Trump would not be sat behind a desk in the Oval Office – and Washington would not have decided to move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].