Why did most of Turkey’s lost pro-Kurdish votes go to ruling AK party?

The ruling Turkish Justice and Development Party's securing of enough seats in parliament to govern alone following Sunday’s elections came as a surprise to many analysts.

According to preliminary results, the Justice and Devolopment Party (AKP) won a total of 23.6 million votes, an increase of 4.8 million votes since the 7 June parliamentary polls, which produced a hung parliament.

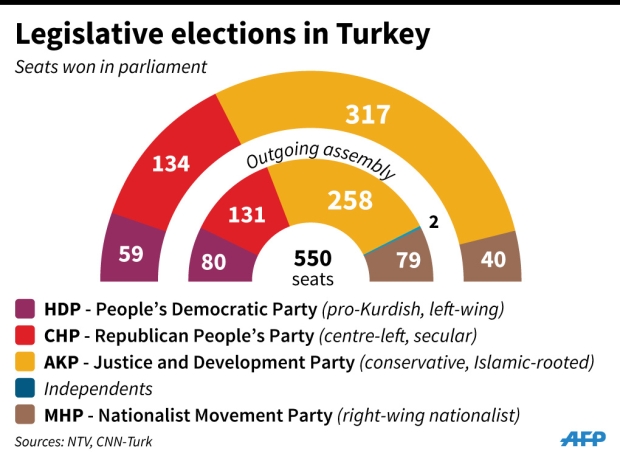

This translates into the AKP winning 317 of the 550 seats at the Grand National Assembly, amounting to 49.4 percent - which means they do not need to form a coalition government.

More intriguing to outside observers, however, is the fact that a large proportion of the seats gained by AKP were won from Turkey’s pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), whose support base had been critical of the government recently.

The HDP lost 21 seats since the last poll. Eighteen of those seats went to the AKP, while the other three were taken from the pro-Kurdish party by the centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP).

Around 1.2 million voters who previously gave their votes to the HDP on 7 June switched to supporting AKP on 1 November.

Despite its significant loss, however, the HDP still managed to secure the 10-percent threshold needed for successful candidates to enter parliament as representatives of the party and not just as individuals, occupying 59 seats.

Kurds traditionally vote for AKP

Prior to last June’s elections, many voters in Turkey’s Kurdish-majority areas have traditionally voted for AKP, which had won every successive parliamentary election since 2002.

But an apparent fallout between the government and many Kurdish voters ahead of the 7 June elections gave rise to the HDP at the expense of the AKP.

“Most of the people who voted for the HDP in the June elections had been voting for the AK Party during all the previous elections,” Galip Dalay, a research director at al-Sharq Forum and senior associate fellow on Turkey and Kurdish Affairs at Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, told Middle East Eye.

But by the 7 June poll, “they were unhappy with certain aspects of AKP’s policies, especially its stance on Syria’s Kurdistan,” said Dalay, in a reference to Turkey’s reluctance to give military aid to Syrian Kurds fighting Islamic State (IS) group militants in Kobane.

“The AK Party policy towards Kobane is the number-one factor (that turned many Kurdish voters against the government),” explained Dalay, adding that “events around Kobane have caused a big psychological and emotional disconnect between the governing party and their previous Kurdish voters”.

However, Dalay also noted that a secondary factor was the AKP’s adoption of “a more nationalist language, which did not go very well with the (Kurdish) voters,” even though the rhetoric was not coupled with any “concrete” action on the ground.

Resumption of PKK militancy

Later on, a number of suspected IS attacks on Kurds in Syria and in Turkey, as well as the resumption of Kurdish separatist militancy against Turkey and Ankara’s response with “counter-terrorism” air strikes, have further worsened relations between the AKP and many Kurdish voters.

However, the surge in violence in the absence of a political will to form a unity government had also led many to long for the days of peace and stability that the country’s north-eastern region enjoyed since the 2013 ceasefire agreement between the government and separatist fighters from the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

“The PKK’s re-initiation of the fight and attempt to declare an autonomous zone did not go well with many Kurdish voters, who blamed the PKK for the rise of violence,” said Dalay.

“This segment of society is in favour of more rights for Kurds through a negotiated settlement. In these (1 November) elections - to some extent - they forgot about (Syria’s) Kobane and focused on the more immediate problems in Turkey,” added Dalay.

Many people in the Kurdish-majority areas were caught in the crossfire between the army and PKK fighters, who are classified as a terrorist group by Ankara, the EU and US, as well as other countries.

“Forty thousand dead since 1984 … That’s enough, it has to stop,” Seehriban Cinak, a resident of the mainly Kurdish city of Diyarbakir, told AFP.

'Kurds have become accustomed to peace'

“The people who until yesterday were accustomed to war have become accustomed over the past two and a half years to peace, serenity, a lack of fighting. Thus the people who got used to that peace, that comfort, will not return to the war of the 90s,” Hakan Akbal, another resident of the region, told AFP.

Many Kurds were blaming PKK-linked fighters for their woes.

“We had to close our businesses for over a week,” Mahmut, 45, an owner of a small shop, told The Guardian. “We feared for our lives and that of our families. Our street was a warzone. They (YDG-H militants, linked to the PKK) dug trenches, erected barricades - we could not leave our home for days.”

“Of all five people in my family, I was the only one to vote for the HDP this time. All the others didn’t vote at all, they were so fed up. All of us had voted for the HDP in June,” he added.

Some Kurdish voters, reported the Financial Times (FT), had welcomed the AKP election victory with a sense of relief.

'AKP gave the Kurds the most rights'

“I want us to enter parliament, but I also think it’s best to have single-party rule,” Tufan Tekin, 40, told the FT. “It’s the AKP that gave the Kurds the most rights in the past. A coalition would not have the power to solve anything.”

The rise of PKK militancy had reflected negatively on the HDP.

“In June, the HDP [emerged] as the main actor of Kurdish politics and as a Turkish opposition party,” Fuat Keyman, head of the Istanbul Policy Centre think tank, told the FT.

“In this election, because of the escalation in violence, because of its calls for [Kurdish] autonomy, it lost the ability to maintain that balance,” he added.

The reluctance of the HDP to boldly condemn the PKK has apparently made the pro-Kurdish party lose many of its voters.

“Following the June elections, the illegal PKK started a campaign of violence - and the legal pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) failed to object to this violence in a clear and sharp way. As a consequence, some Kurdish votes went to AKP as well,” wrote Ahmet Hakan on the website WorldCrunch.com

Joost Lagendijk, a Dutch expert on Turkey, also attributed the loss of HDP votes to PKK militancy.

“The HDP suffered considerable losses in its strongholds in southeast Turkey of all places, which indicates that many Kurds reject the PKK and the return to violence,” wrote Lagendijk.

Nationalists also voting for AKP

Ironically, the resumption of PKK militancy has also helped the AKP gain votes from the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which lost 37 parliament seats - slightly less than 2 million votes - to the AKP.

As more Turkish policemen and soldiers were killed by PKK militants, the country's nationalist sentiment appears to have turned towards the government for retaliatory action, instead of a party that has no hope of securing a majority in the parliament like the MHP.

This means that the resumption of PKK militancy has given votes for the AKP from two opposing sides: the nationalists and the Kurds.

However, Dalay warns, if AKP does not tone down its nationalist rhetoric then Kurdish voters may go back again to the HDP once the dust settles.

On the other hand, Kurds are still short of their full rights, especially with regards to their unacknowledged identity in the constitution - and the AKP is the most likely party to help them gain those rights, added Dalay.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].