'We will be heard': How the women of Turkey are fighting for their rights

ISTANBUL, Turkey - Riot police, clad in black, use their shields to form an unbroken line and block access to Istiklal Avenue, the city's main street.

Before them is Tunel Square and a sea of purple-clad protesters, shaking tambourines, blowing whistles and clamouring to be allowed to walk forward.

The protest signs bob up and down in time with the chants.

"Will we tolerate male violence?"

"No!"

"Will we allow our rights to be taken away?"

"No!"

The sheer mass of people trying to enter the narrow avenue creates a bottleneck.

Feride Eralp, one of the organisers of the march, goes back and forth between the front and back of the protest, relaying the chants. She's only 28, but she's been on the microphone, leading women's protests, since she was 21.

"No!"

"Will we lose one more person?"

"No!"

By the end of the evening, they will have faced down tear gas, rubber bullets and police dogs to make their voices heard.

The grim toll of domestic violence

For the past two decades, women have come together at the foot of Istiklal Avenue on 25 November to mark the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women.

But this year the protest is angrier than before, the frantic urgency of the crowd partly spurred by the level of reports of domestic violence in Turkey.

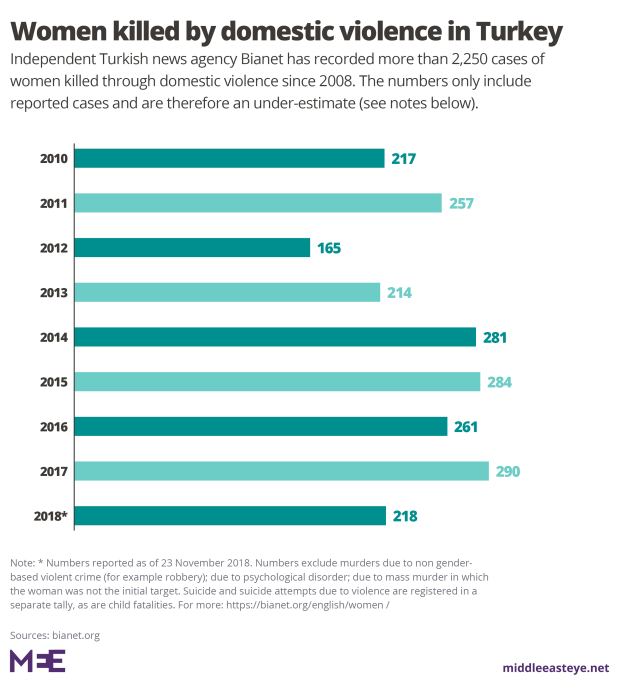

Bianet, an independent Turkish press agency, tallies media reports of woman who have been subject to domestic abuse based on their gender. The numbers it collates are an under-estimate and do not include those cases which have gone unreported.

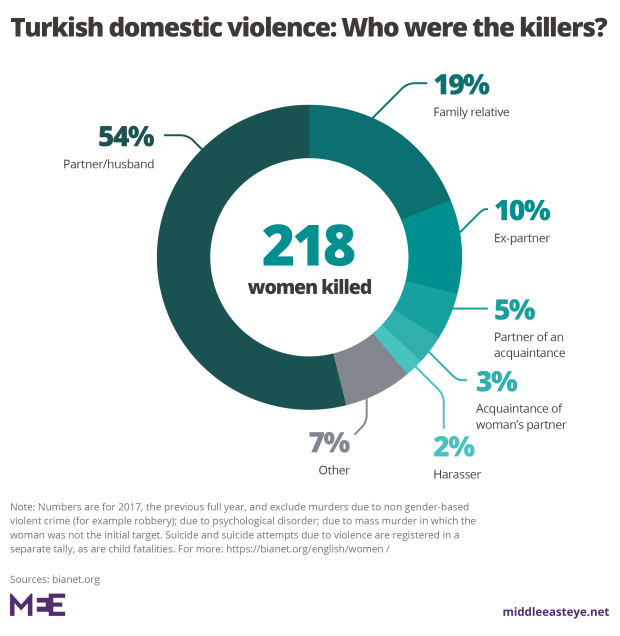

So far this year the toll of women killed by their abusers stands at 218, despite some improvements in laws introduced by the government as well as the efforts of women's groups to raise awareness and advocate for those exposed to abuse.

The turnout has also been helped by the high profile of social media posts from women who say they have been harassed or abused by their colleagues in the entertainment industry, echoing the #MeToo movement in the United States and elsewhere.

In June, Ozge Simsek, 19, a costume assistant for a TV show, accused veteran actor Talat Bulut, 62, of sexual harassment on set. Hande Ataizi, an actress, then said that he had harassed her 18 years earlier. No charges were brought against Bulut, who says: "These claims, which have nothing to do with the truth, have upset me and my family."He is now suing Simsek for 100,000 Turkish lira ($19,242) in non-pecuniary damages, according to Turkish media reports.

In October, actress Elit Iscan, 24, said on Instagram that she had been harassed by colleague and actor Efecan Senolsun, 26. In his own Instagram post, Senolsun denied the allegations and said: "We were good friends before that day. ... [Iscan] started saying unrealistic things to influence public opinion."

But the greatest publicity has been given to the accusations by chart-topping pop star Sıla Gencoglu, who is better known as Sila and who told her 5.7m followers on Twitter that she had been physically abused by comedy actor Ahmet Kural, with whom she was in a relationship. "I've chosen to not remain silent about what happened to me," she wrote.

The case has been referred to a reconciliation office before it proceeds to trial, despite the fact that the use of such offices in domestic violence goes against the Council of Europe's Istanbul Convention on violence against women, which Turkey was the first to sign.

Kural has been told to stay away from Gencoglu for three months under a protection order, which was issued on 31 October and is valid for three months.

On 28 October Kural said in a statement that he did not accept a single one of the "ugly allegations" against him, that he had only held Gencoglu's arm and that he would give details of what he has described as a "mutual scuffle" between the couple to the prosecutor. "I don't accept anything else besides this. I'm very sorry that I will unfortunately be pursuing legal options concerning this."

But the support that Gencoglu has received online and from entertainment stars has galvanised the women's movement.

Elif, a 21-year-old student at the protest, does not give her name amid fears for her safety but says: "I was feeling nervous before I got here, but now I feel the power." She says she draws strength from the high turnout as well as the placards, which include one of Kural with a bright red "X" over his mouth.

Eralp says: "There's a kind of understanding that this [abuse and harassment] is not okay that we are getting, at least on the visible level. That's a gain for the women's and feminist movement over the years."

When a march gets banned

The news has sunk in for the protesters gathered at the approach to Istiklal Avenue: the government has banned the march.

Many were not expecting this: previous demonstrations involving thousands have been allowed to take place on this date, as well as on International Women's Day in March, since 2011. This is the first time in years that police have intervened in an event on this scale.

But, Eralp says, the women come here every year and expect their voices to be heard. "Violence against women is a very raw subject," she says. "Outrage can't be contained to a single square. You can't let women blow off steam for 10 minutes and then disperse the crowd."

And so the organisers coordinate an attempt to break through the police lines, with the women in front pushing against riot shields.

Eralp is right in front of the police line throughout the near hour-long standoff, bullhorn in front of her and calm: the more the police push, the more the women beat their drums, yell and blow their whistles.

As the tear gas hits the square, Eralp tells the crowd to sit down so that they can’t be moved. "Don’t leave!" she coughs.

'Why were you out at 4am in the morning?'

Women's rights in Turkey look good on paper: for example, in 2012, the government introduced Law 6284, which allows women to press charges against their alleged abuser on verbal testimony alone, and which allow protection orders to be made against the accused.

But while the law may be strong, implementation is weak. Itır Erhart is an associate professor at Bilgi University who works on gender in Turkey. She says that the number of women killed each year has to do with how domestic violence is treated by the government.

When you actually face the judge, when you actually go to the police, that's when discrimination begins

- Itır Erhart, Bilgi University

"When you actually face the judge, when you actually go to the police, that’s when discrimination begins," she says. "For example, if you're harassed, the judge may ask you things like: 'Okay, why were you out at 4am in the morning?' or 'What were you wearing?'"

In October, the Council of Europe's Group of Experts on Action Against Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO) published its report on Turkey's adherence to the Istanbul Convention, a legally binding, Europe-wide framework for combating violence against women.

The report noted several "serious concerns" about the lack of data gathered by Turkey on domestic violence and criminal cases on the subject.

It also noted widespread issues of "underage and forced marriages, psychological violence and stalking, increasingly restrictive conditions on independent women's organisations" and "deep-seated, restrictive and stereotyped views of women's roles in Turkish society" all the way up to the highest levels of government.

Lisel Hintz, a professor of international relations at John Hopkins University in the US and who studies media and gender in Turkey, references these stereotypes, and says that many of them are supported by government decisions. In 2011, for example, the Ministry of Women and Family Affairs was changed to the "Ministry of Family and Social Affairs" by removing the word "women".

Hintz also says that how politicians and public figures speak about women has also enabled higher levels of violence. "There has been a pervasive shift in what's acceptable towards women - based on laughing out loud, based on what they wear, based on having the gall to try to assert an independent role in society," she says.

"So for me, yes, those numbers [of women killed ] are terrifying, but it's also a shift in what's acceptable on a more casual, informal level."

And while social media have allowed women to share their stories, Hintz says that the potential impact of the movement is hampered by the media environment and the "indirect or direct control" that the ruling AKP party has over most of the large media companies in Turkey.

"Yes, there's social media, but in terms of what is being recognized and distributed and disseminated, television- and newspaper-wise, those kinds of things aren't necessarily going to get that coverage."

Rubber bullets and tear gas

Back at Tunel Square, Eralp is acutely aware that if the protesters give way to the police then the march will be lost.

"In Turkey," she says, "if you do that, it creates this kind of despair, constantly being limited when you're trying to raise a voice that you think is very, very rightful."

With the ban, the women's march joins the list of rallies that have now been blocked by the government since 2015, including LGBT Pride parades. But the women refuse to let the police response define them.

After enduring the tear gas for almost an hour, the organisers suddenly announce that the protesters should continue the rally in the side streets.

Elif and her friends head for a back alley, marching and chanting: "Women, life, freedom!" But others encounter riot police, who now deploy rubber bullets and tear gas.

I feel both the anger and the joy of being together with women

- Feride Eralp, protest coordinator

Eralp's group makes it all the way down Istiklal Avenue, where they read a press statement on the bullhorn and then disperse.

Reaching the other side of the avenue is a victory in her eyes. The women didn't step back. They made their voices heard.

"I feel both the anger and the joy of being together with women," she tells the crowd. "Struggling against something that I really do think we have the power to change, maybe not in one day but eventually.

"The streets aren't the only way women raise their voices in Turkey. But I do think it's the streets that keep us going."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].