Shut out from power - what next for Tunisia's Islamists?

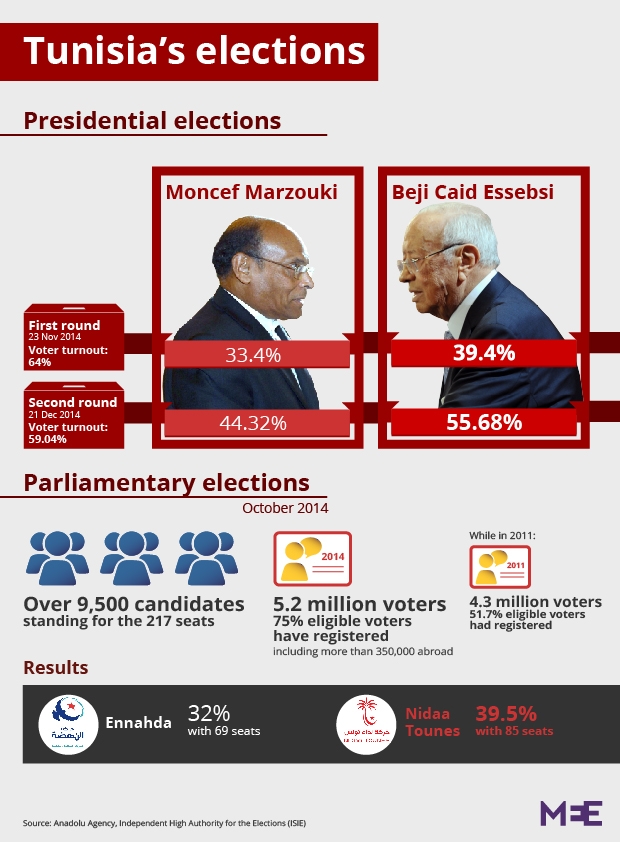

Tunisia, the home and heart of the Arab Spring, held presidential elections on Sunday, the first since the country’s revolution in 2010.

The winner of the vote, 88-year-old Beji Caid Essebsi, is a former interior minister who now heads the secular coalition that took power last month from Ennahda, the Islamist party that swept elections after president Ben Ali was toppled in 2011.

Thousands of supporters of Essebsi – a jovial and bespectacled lawyer whose charismatic politics are modelled on independence leader Habib Bourguiba – took to the streets of Tunis on Monday clanging pots and chanting "Beji President!" as they celebrated their country's "final step" towards full democracy.

Essebsi’s critics, the young and unemployed who took part in the 2011 protests, see his victory as a throwback to old, regime-style politics; where a handful of elite Tunisians run the show.

With Essebsi’s secular party, Nidaa Tounis, now in control of the parliament and presidency, the spotlight is on Tunisia’s Islamists who, after a brief spell in office in 2012-13, find themselves shut out from power.

Rachid Ghannouchi, the pragmatic political activist who heads Ennahda, announced in September that his party would not run for the presidency, the latest in a series of concessions designed to show there was no risk of a total take-over of power by Islamists.

Wither Ennahda?

But while Ghannouchi’s cautious approach to politics may have spared his party the fate afforded Islamists elsewhere in the region, such as Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood ousted by the military in 2013, his long-view strategy remains a gamble.

If the Islamists are charting a return to power, analysts say, they are relying on a set of uncertain expectations: that their secular opponents falter in office, that the patience of their supporters – especially the young and frustrated – does not wear thin and that their party's leadership is capable of forging alliances with political groups with whom they have little in common.

An hour-long television interview last week in which Ghannouchi dismissed fears of a return to a one-party dictatorship, may have offered some reassurance to Ennahda supporters. “The police state, the single-party state is not about to return. The days of president for life are over,” he said.

Nevertheless, Essebsi’s victory at the polls on Monday concludes a resoundingly negative verdict passed by Tunisians on Ennahda after two years in government.

Senior Ennahda figures concede that the job of running the country, and especially the economy, was more challenging than they had anticipated. Ghannouchi told supporters that “five years out of power could be salutary.”

One reason for bowing out of the presidential race, analysts say, is that Ennahda is banking on joining a broad coalition government expected to be formed in early 2015 by Essebsi’s Nidaa Tounes party.

Alliance with Nidaa?

But forging an alliance with Nidaa Tounes -- a two-year-old party of former Ben Ali supporters, union leaders, and leftist politicians unified in their opposition to Islamism in Tunisian society -- will be tough.

"Many in Nidaa see Ennahda as a cancerous, undemocratic element opposed to a modern, secular Tunisia… so going into a coalition with Islamists would be a bitter pill to swallow," said Monica Marks, a Tunisia-based analyst from Oxford University.

"Likewise Ennahda’s base believe a coalition with Nidaa would mean a coalition with old regime oppressors – many of the same people who supported politically-motivated oppression and even torture of Islamists are now in this party or vocally supporting it," said Marks. "Some I've talked with even describe it as nauseating, and say an explicit coalition with Nidaa would hasten their exit from the party. These are deep antipathies that would be very difficult to walk back."

Despite its victory, Nidaa Tounes has not been able entirely to shake off the reputation that it represents an attempt by members of the previous ruling party, the Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD), to regain influence.

In what was in effect a single-party state, the RCD built clientelist relations running from taxi-drivers and corner-shop owners, to non-governmental organisations, lawyers, senior civil servants and—importantly for its funding—business people. Although the RCD as an organisation is long dead, these networks appear to have come back into play on election day.

Political analyst Youssef Cherif doubts Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes could work together in a coalition: "It would be ideal if they do, a perfect case of checks and balances, less polarisation, reaching to different regional and international stakeholders etc." However, Cherif considers cooperation unlikely as the two parties have distinctly different visions of Tunisia's future.

On a leadership level, Ghannouchi, an Islamist scholar who lived in exile in Britain during Ben Ali's rule, and Essebsi, who served under both Habib Bourguiba and Ben Ali, know how to work together, explained Cherif "They did meet several times, and they never attack each other personally."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].