Aid workers fear donor fatigue could hit anti-polio efforts for Syrian refugees

Health workers in Za’atari, the sprawling Jordanian camp for refugees from across the border in Syria, vaccinated over 18,000 children from polio in a five-day campaign earlier this month.

With the war in Syria about to enter its fourth year, long-term health interventions like these are becoming ever more vital for the refugee population living in Jordan and elsewhere, say workers.

However, with donor fatigue well entrenched and the Ebola crisis attracting much of the money available for world health campaigns, many fear that funding will be hard to come by in 2015.

'Unprecedented' polio outbreak in Syria

Za’atari camp in Jordan’s northern desert, established in 2012 to house some 15,000 people, is now home to over 80,000 refugees fleeing the protracted war in neighbouring Syria.

The informal settlement is now Jordan’s fifth largest city in terms of population, and aid organisations are struggling to meet the health needs of the camp’s inhabitants, which stretch from emergency operations to secondary services like eye-glasses and hearing aids.

Over 1,000 children have lived their whole lives in the camp, and with an average of 10 newborns delivered daily, the organisations working in Za’atari are increasingly having to consider how to provide services all the way from cradle to grave.

A major concern is preventing an outbreak of polio, a contagious disease usually hitting during childhood and that can lead to paralysis and death.

Successful vaccination campaigns have seen polio eradicated in most of the world, with the disease mostly confined to Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan.

However, new cases were reported in Syria in 2013, something Louise Joyce of Human Appeal described as “unprecedented.”

“Syria was previously a middle-income country, so an outbreak of polio was unheard of. And with the huge movement of people [caused by the war], the impact can easily spread across borders,” including within the sprawling Za’atari camp.

“After the collapse of the health system in Syria, children were coming into the camp without basic immunisation,” according to Julianne Whittaker, a programme co-ordinator with International Relief and Development (IRD), the organisation that delivered the most recent round of polio shots.

“People would arrive in 2014 with three-year old children – during the three years of the Syrian conflict, there was never a health provider to vaccinate that child.”

In response to this, organisations like IRD have organised campaigns to vaccinate five-year olds, in tandem with their Jordanian counterparts, as well as younger children.

In the most recent drive, IRD gave polio shots to 18,556 children in a campaign run throughout the camp between 7 and 11 December.

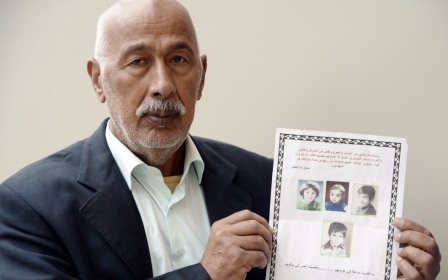

Mohammed, a Za’atari resident and former nurse who has had four of his eight children vaccinated against polio in the camp, said he had been reluctant at first.

“During the first vaccination campaign [in 2013], I hesitated to get them vaccinated here in Za’atari. We were sure that we would return back to our country after a few months, and would then be able to do it in Syria. But unfortunately, the situation in Syria just became worse and we are still here.”

Among those distributing the vaccine was a group of 120 volunteers drawn from within the camp’s population, made up of Syrian doctors, nurses and medical students who fled the bloodshed and ended up at Za’atari.

Danger of donors becoming 'anaesthetised' to Syria crisis

These immunisation drives, Whittaker said, must be done on a regular basis if they are to be effective – IRD has organised nine such campaigns since late 2013.

“There is nothing sealing in communicable diseases in Za’atari and preventing them from breaking out within the Jordanian host community.

“Everyone has an interest in ensuring [an outbreak] doesn’t start somewhere.”

Although the programmes has support from the Jordanian government and UNHCR, which jointly administer the camp, organisations working on the ground fear that donor funding won’t be forthcoming as the war in Syria enters its fourth year.

“A lot of the bigger charities are now fully stretched,” according to Simon Green, spokesperson for Human Appeal.

“Their attention is drawn to many areas of the world, and Syria is at risk of slipping out of the public consciousness.

“In the fourth year of the conflict, it’s important that people don’t become anaesthetised to what’s going on in Syria.

“As the war continues, it’s also becoming increasingly difficult to negotiate and do cross-border work. But I’m not less optimistic than I was last year. The work simply has to be done.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].