'Sinai is our Vietnam': Horror stories Egyptian soldiers tell from the front line

Eating fried-chicken sandwiches and smoking shisha tobacco inside a local cafe, Ahmed and Mohamed debate how to spend the coming hours before returning to base.

The two soldiers, on a weekend pass from their battalion, had just come back from a funeral for a friend who was killed when militants ambushed his battalion in northern Sinai.

We saw the worst of what people can do to each other, and saw how conscripts are cheap lives

- Moataz, former army medic in Sinai

Tucked in the cafe, sitting under a photoshopped poster of Egyptian footballer Mohamed Salah clutching a World Cup trophy, they hide from military police, who forbid soldiers in uniform from mingling with civilians.

"They gave him a military funeral with a band, and they will name a school after him," says Ahmed, 20, puffing heavily on a water pipe and sipping sugary Turkish coffee. "You should have seen it."

Mohamed, 21, finishing his second sandwich, shakes his head. "I don't want to have a school or a mosque named after me," he says. "I want to live my life."

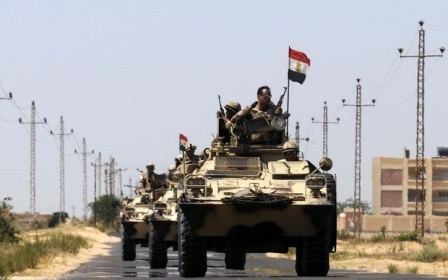

Ahmed and Mohamed are two out of thousands of young Egyptian men who have been deployed to the Sinai Peninsula since 2011 to counter a militant insurgency.

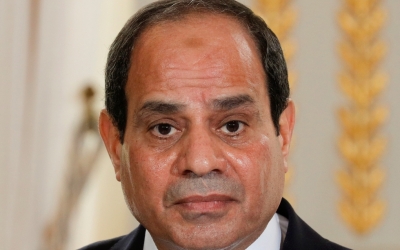

It's a battle that Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has championed from the start of his presidency, using repeat attacks as a justification for keeping the country in a state of emergency and pursuing military campaigns that have killed hundreds of civilians and displaced thousands more.

In an interview with 60 Minutes on US broadcaster CBS which the government reportedly tried to stop before it was aired earlier this month, the president disclosed that Egypt's military had been working for years in cooperation with the Israelis in Sinai.

But seven current and former soldiers who spoke to Middle East Eye say the war in Sinai - which has seen more than 1,500 security personnel killed in action according to a count compiled by independent researchers who maintain anonymity for their safety - has left them haunted and psychologically broken, many arriving with only 45 days of training. MEE could not independently verify the researchers' figures.

The culture in the Egyptian army, military personnel say, leaves no place for trauma or weakness, with several saying they were forced to seek private psychiatric help because the military does not provide it.

Two military spokespeople who spoke with MEE refused to answer whether psychiatric help was offered. One officer affiliated with the state intelligence apparatus told MEE: "When morale is low, officers are the ones who act like shrinks. In the more centralised bases near Cairo or big cities, clerics often come and chat with the soldiers."

Yet soldiers say what they experienced has completely altered their lives and requires professional untangling.

"It is a horrific moment to see someone collect pieces of your friend who you knew for two years and whom you just had a meal with that morning," said Sameh, 27, a non-commissioned officer serving in Sinai.

"If soldiers are depressed, they either don't show it or request to go on vacations."

Moataz, who served as a military medic in Sinai, said: "We saw the worst of what people can do to each other, and saw how conscripts are cheap lives. Some people were fine with it, but for me something in me is not the same."

Insurgency and uprising

The current insurgency in Sinai has roots that go back long before the 2011 uprising and then the 2013 coup.

In the early 2000s, the Sinai-based militant group al-Tawhid Wal Jihad formed a spiritual alliance with al-Qaeda, committing several high-profile attacks on tourism resorts among other targets which killed dozens of people.

The state responded with a crackdown on militants in Sinai who, in the chaos following the 2011 uprising, found a perfect moment to avenge the years of ill-treatment at the hands of the police and the army.

At this time another militant group, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, which had its roots in al-Tawhid Wal Jihad, became active, targeting gas pipes in Sinai running to Israel and Jordan.

After Sisi overthrew president Mohamed Morsi in July 2013 and after the Rabaa Square massacre of protesters in Cairo the following month, the group ratcheted up its terror in Sinai with nearly weekly attacks, accusing the army of displacing local civilians and launching air strikes on civilian homes.

In 2014, disputes within Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis resulted in a majority of the group pledging allegiance to the Islamic State group (IS) and a change of name to Sinai Province, claiming to be an IS branch.

Since the start of the insurgency, Egypt's wave of ultra-nationalism created propaganda and a narrative of the "Egyptian fighter" as religious, disciplined, neat and a "born to kill" fighting machine. In 2016, the defence ministry released a film showing the daily life of an Egyptian conscript.

But many of the soldiers serving in Sinai haven't been able to choose: they were conscripted. According to the Egyptian constitution, men aged 18 to 30 must serve in the military for at least 18 months, followed by a nine-year obligation to serve if called up for duty.

Young men who are medically unfit, the only sons in their family, some dual nationals and individuals known to have Islamist inclinations, are regularly exempt.

While IS militants are trained in guerilla and desert warfare and house-to-house combat, with possible military experience in Gaza, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, the bulk of Egypt's fighting forces are conscripts who have spent only 45 days in boot camp to learn how to be soldiers.

One of those conscripted was the former medic, Moataz, whose battalion was one of the first to arrive on the scene after the group, then still known as Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, staged a major attack at a checkpoint in northern Sinai in October 2014.

In the military, there is nothing called 'I am sad' or 'I am not feeling well'. That is why only men go to the army

- Khaled, former soldier serving in Sinai

One of the most deadly attacks to date against the Egyptian military, at least 30 military personnel were killed at the checkpoint. Moataz's job as a medic was to quickly assess the dead and wounded, and then start treatment.

He said he counted 19 bodies, with many of the remains scattered across the scene, after the explosion of roadside bombs.

"Body parts were everywhere," Moataz, now 25, told MEE. "It is a scene that I will never forget.

"The rest of the bodies were firstly wounded and then executed by gunfire. Some bodies had more than 20 bullets in their heads."

Now a physician working privately in Qatar, Moataz was discharged in 2017, but he says he still has nightmares about his service and sees a psychiatrist.

"To us and many other conscripts, Sinai was our Vietnam," he said.

Khaled, now 23, was a 20-year-old conscripted soldier serving in the north Sinai city of Rafah in July 2017 when militants attacked a checkpoint that was blocking the flow of goods and people from Gaza.

Twenty-three military personnel were killed after a suicide bomber struck the checkpoint at dawn, but Khaled said the attack continued.

"A lot were killed and wounded, and then the jihadists kept coming. Whoever was still alive kept shooting, but they kept coming," he said.

"I was injured in the stomach by a bullet. I lay on the ground and could not move, but I heard my brothers scream."

Khaled was discharged from the army after the attack and now receives a pension, but he has not sought psychiatric help.

"In the military, there is nothing called 'I am sad' or 'I am not feeling well'. That is why only men go to the army," he said.

Lack of training, equipment

Omar, a special forces officer with the Egyptian police who was stationed in Sinai in 2013, told MEE that the 45-day boot camp for conscripts, paired with a lack of sufficient equipment, had left many of the young men serving in the peninsula more of a liability than an effective fighting force.

"Unlike forces around the world where a recruit has to be fit and well-trained for combat operations, conscripts are often a problem for the war against terrorism," said Omar. "They are either unmotivated or overexcited. And both make mistakes."

Until 2014, the jihadists had night-vision goggles but we didn't

- Omar, Egyptian police special forces officer who served in Sinai

Rookie soldiers were given equipment from the 1990s, but even officers like Omar who had larger weapons' budgets did not have sufficient equipment, he said.

"For example, until 2014, the jihadists had night-vision goggles but we didn't," Omar said.

The weapons disparity that Omar describes is a symptom of a historic culture within the military which sees maltreatment and abuse passed down the line of command.

The military source affiliated with intelligence told MEE that officers must be hard on soldiers as any other military would be. "Otherwise, how can the soldier obey his superiors," he said.

"If there is war, we have to guarantee that the soldier can obey without questioning, without remorse. This happens all over the world."

But even soldiers like Mourad who stayed far from the front line in Sinai speak of bullying that they found intolerable and damaging.

Mourad, now 24, graduated from the faculty of fine arts in Helwan University before he was conscripted into the army.

"I was so naive when I was young to believe that I was going to serve my country," he told MEE. "After the basic 45-day training, I realised that I just need to pass this year no matter what, even if I was to be a sales person in one of the army's outlets."

But instead of a sales role, Mourad was transferred to the Third Army in Sinai, serving in a battalion officers' mess hall by day and the dorms by night.

"I studied sculpture and design for four years, and here I am cleaning the officers' bathrooms, officers who are younger than me, and getting yelled at and insulted," he said. "On purpose, officers insult you and aim to break your personality. We are treated like slaves or dogs."

But with nationalism running high and in the dog-eat-dog world of the military, Mourad said he felt he couldn't afford to complain or get angry, and instead had to adapt.

"I learned to steal, lie, cheat and be a hypocrite, and turn a blind eye to injustice. I even started to bully and intimidate younger soldiers," he said. "But that is what happens when oppression takes place in a chain of command: everyone will eventually oppress whoever is lower than him."

Mohamed, a graduate of a technology institute in Alexandria, was a popular footballer for a local club and had hoped that his skills on the pitch would earn him a place on one of the armed forces' football teams, and consequently make his conscription experience easier.

Instead, he is serving two years in the Second Army and currently handles a soldiers' canteen. Mohamed says he too has become abusive in the military.

I learned to steal, lie, cheat and be a hypocrite, and turn a blind eye to injustice

- Mourad, former soldier serving in Sinai

"I have learned, sadly, to become a bully. You have to prove your personality by being aggressive and showing you are a hard man otherwise you will be run over," he said.

While running the canteen, the former sportsman said he has had to cheat in order to stay out of trouble.

"The officer wanted his cut in the profit of the canteen, which originally has to go to the battalion's budget," he said. "In return, I had to cheat and forge the papers, and even buy expired snacks and food."

Defending his actions, he recalls a famous saying among Egyptians - "The military tells you to make do" – and said he had to "make do" to get by.

"I know it is a sin, but inside the base there are people who do not know God. Otherwise, I would not have passed my days," he said.

'Just kids'

Like Mohamed, Ahmed, a former al-Azhar University student, believed he had enough connections to complete his military service in one of the air defence battalions in Cairo, an administrative post or in one of the military's companies, where work is minimal and the conscripts can spend their nights at home.

But when he graduated from university, he was deployed to north Sinai to serve in the Second Army's 2nd Infantry Division.

Forty-eight days of Ahmed's life were spent in al-Galaa boot camp in Ismailia wearing ill-fitting clothes, going without regular clean water and food, and being forced to stand in the sun for hours, an experience he describes as "hellish".

"It is the worst that I have seen. I used to cry every night, but I wouldn't show it so as not to get bullied," said the well-built 23-year-old.

"If I had not been 'sentenced' to go to the military, I would have studied Turkish and worked as a translator," he told MEE. "I wanted to travel and meet different people, do wrong things and learn things, not sit in a tin-made kiosk carrying an old and rusty 30-kilo machine gun."

It has been more than six months since his boot camp. After every 40 days on base, Ahmed is given five days of vacation. He spends two of them travelling to get home and back. "When I am off, I basically sleep and eat, meet my girlfriend, and watch films, anything a young man would do."

Other soldiers who are given weekend passes or shorter leave end up in Suez or Ismailia to rest before returning to their bases in north Sinai.

Said, a taxi driver and salesman in Suez, often ferries conscripts from bus stops to local hostels.

“Mostly, they want a decent place to sleep and good homemade food. A lot of them want hash. They are just kids," he told MEE.

"Often there is a group who try to cheer up one soldier among them who looks sad. God only knows what they see in Sinai."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].