In pictures: The taxi driver capturing raw life in Istanbul

Sahintas's mother was pregnant with him when, along with his father and older brother, she came to Istanbul. It was the middle of the 1960s, and they settled in a shanty town in Rumeli Hisarustu, near the Bosphorus Strait. “My dad went to work, my mum did housework,” Sahintas recalls. “There was no running water in the homes, she used to carry water with pails and wash laundry, dishes and us three kids.” The photo here, shot in 2015, shows two Syrian refugees (Sevket Sahintas)

After failing school, Sahintas, who is now 53, worked in a garage repairing cars then, like most Turkish men, joined the military. When he returned to Istanbul he became a cab driver. “I only knew the neighbourhoods very close to where I lived,” Sahintas says. “I didn’t see any places outside of that. My childhood just passed by working… When I began driving a cab I didn’t know one-thousandth of Istanbul.” (Sevket Sahintas)

In 2004, Sahintas began working the night shift, then started taking photographs. He still remembers the moment that led to him taking up photography. “I was driving the cab at night, while waiting for a customer. It was dark, it was very cold — it was winter. I watched a man trying to sleep on the street. I became sad about this man’s situation and considered what could be done. And I got a camera, a small camera. I started to take photographs with it.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Sahintas says that he tries to make the most of being a taxi driver. “If I had the opportunity, of course I would have wanted to do something else, because driving a taxi in Istanbul is really very hard. Sometimes it takes 15-20 minutes to go 100, 200 metres, when there’s a lot of traffic. And it’s not a very prestigious job. And it tires you.” (Sevket Sahintas)

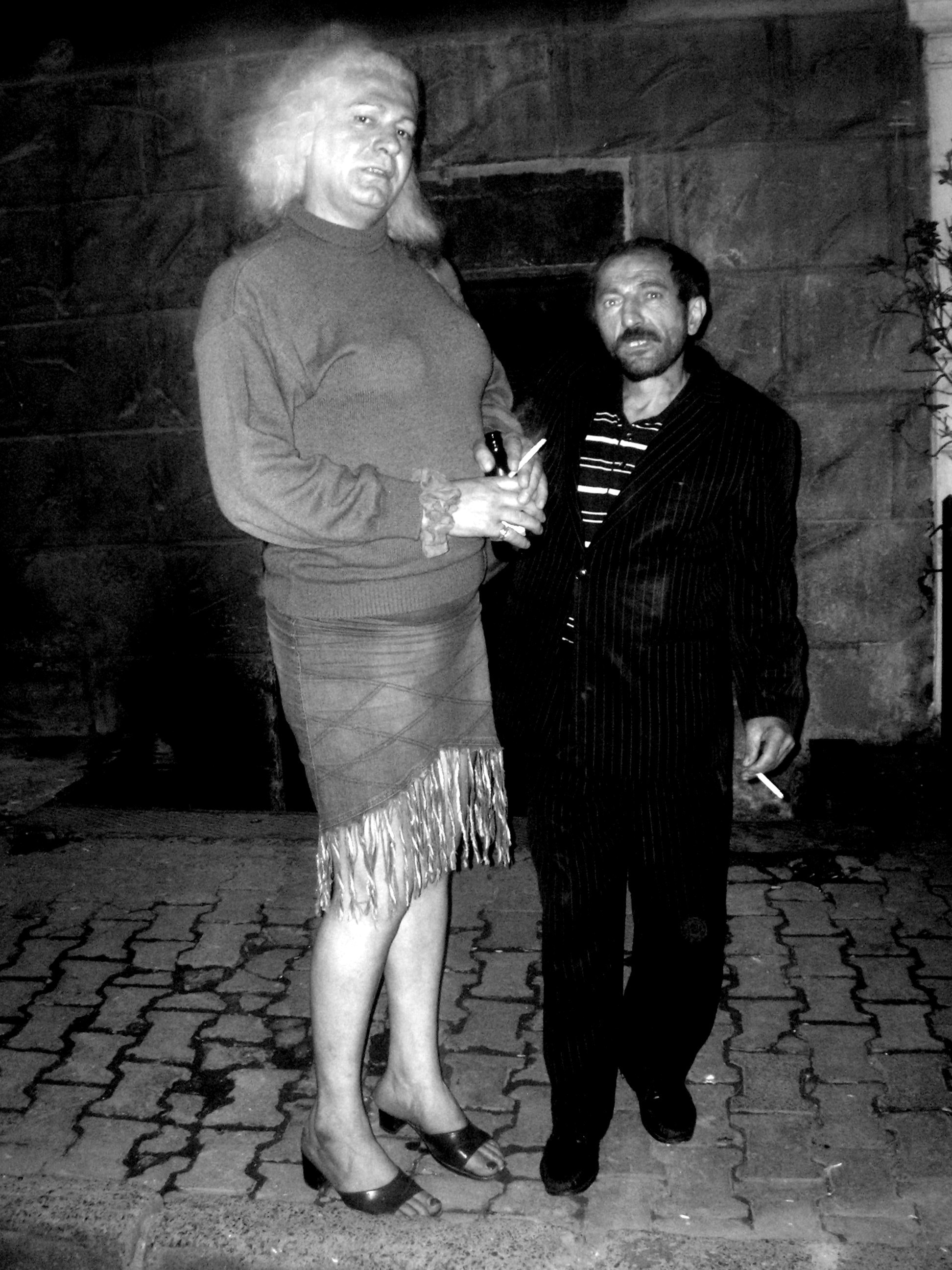

Sahintas says that the transgender and transexual community in Istanbul face a tough life. “Sometimes they are killed in Turkey, as you know, for being trans.” He also began to notice other regulars on the streets. “Prostitutes. Scrap collectors. Child workers - there are younger and older scrap collectors. They also began to show up in the photos.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Photographing street life at night came with many challenges – so Sahintas devised tactics to win his subjects’ trust. “I’d say: ‘Do you have a light?’ Because most of these guys smoke. I’d take their lighter, light my cigarette and then I'd give them a cigarette. Or I’d say: ‘Your dog is pretty, can I take their picture?’ They’d say take it. I’d take the dog’s photo and then I’d say let me shoot one of both of you if you want.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Sahintas is also aware of the dangers. “I always thought to myself: ‘I could die one day at the hands of someone I’m trying to save’. It would be tragi-comic, then, because the person you wanted to hear from could kill you. But like I said, I really wanted to do this. So I had no other option. You simply have to put your life on the line, and take a photo. That’s what I did. I’ve lived until now, and nothing has happened.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Then there are the youngsters. "Most of the young children, maybe as many as 60 percent of them, are kids who escaped youth shelters. When we talk to them, they say they are escaping their older counterparts. They put the 12-year-olds and 18-year-olds in the same place, and those 18 or 17-year-old kids beat those young kids up.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Scrap collectors are common on the streets of Istanbul - such as this one Sahintas photographed at work on Istiklal Avenue, in Beyoglu, one of the city's busiest districts. “All the newspapers published full-page reports about my photographs. I actually showed them. But not a single administrator, mayor, politician called me up and said: 'What can we do, thank you, you enlightened us.' And for that reason, I’m not sure if I met my objective, if my photos met their objective.” (Sevket Sahintas)

A homeless man lies on the ground, surrounded by a crowd while waiting for an ambulance. “Istanbul, as you know, is really one of the most beautiful cities in the world," says Sahintas. "You see Europe from one shore, you see Asia from another shore. It’s a very charming city. And I used to see it that way before these photographs. But now, along with the people out on the dark streets, it lost a little more of its beauty in my eyes.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Sahintas has also recorded the arrival of Syrian refugees to Turkey, an influx that began several years after he started taking photos. “They were settling in an abandoned area undergoing urban renewal. I saw a report on TV. When I heard that they lived in Suleymaniye, I went and took photographs of Syrian refugees in Suleymaniye.” (Sevket Sahintas)

For this portrait, also taken in Suleymaniye in 2014, Sahintas photographed Syrian refugee children wandering the streets. In the background an empty building burns. Turks living in the area, Sahintas says, were not happy with the new arrivals. “I can’t say Syrians have been very well-received in Turkey.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Here, Sahintas photographed a refugee sheltering amid a shattered building. “There are many young people who end up on the streets, and without a helping hand they end up on bad paths, and most end up dying or in jail. Our only advantage over them is the luck we’re born with. That’s the only thin line separating us. It’s a thin line, but it goes on for a lifetime.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Sahintas has given up the night shift, and takes many photos during the day, including this portrait of a Syrian refugee. Yet he still recalls what he saw at night - and cannot help but be affected. “You think about how they’re out in the cold. When I was in the taxi, stopping and going, I cried… I couldn’t take it out on the road, and I was crying.” (Sevket Sahintas)

A young refugee sits by the remains of a bull, slaughtered for Eid. “I’m just showing these photos,” says Sahintas. “But I want the people or politicians who see them to help these people. This is the aim of my photography. If you saw, say, a person on the street in an emergency, hit by a car, you’d yell for a doctor or call an ambulance. I’m in the group that sees. I see and I yell for a doctor. That’s my role.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Young refugees wander around an empty building in 2014 while outside a snowstorm rages. “Istanbul used to be more green, there was more open land. Now, we are getting lost in the buildings, you don’t see Istanbul, you see the buildings. That’s why old Istanbul was more beautiful. There was more neighbourliness. When I was a child, our neighbourhood was a shanty town. Then later we got apartment buildings, and you don’t say hi to even your closest neighbours.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Sahintas is uncertain how much longer he will stay in Istanbul. “I’m thinking of moving to the Aegean at the first chance I get,” he says, “because Istanbul has stopped being a liveable city. It’s very crowded, the streets are the same. Now, Istanbul is ugly. I don’t want to witness this while I’m alive, so I want to leave Istanbul.” (Sevket Sahintas)

Sevket Sahintas's photography appeared in his debut exhibition, The Other Side of the Night, in 2009. He has also been the subject of While Everyone Else Sleeps, a feature documentary. In late 2017 he began shooting a documentary about street children for which he is still seeking supporters. While many of his photos were taken at night, he now drives during the day. Follow his photography on Instagram at @sevketsahintas (Jeffrey Bishku-Aykul)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].