'We do not have freedom': Haftar's forces accused of war crimes in Libya's south

Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) has been accused of war crimes and violent abuses in Libya’s south after fresh gains in the area, including a much-coveted oil field.

The LNA, whose forces are vying for control over Libya’s neglected and oil-rich south, is fighting on behalf of an eastern-based government, one of two rival administrations.

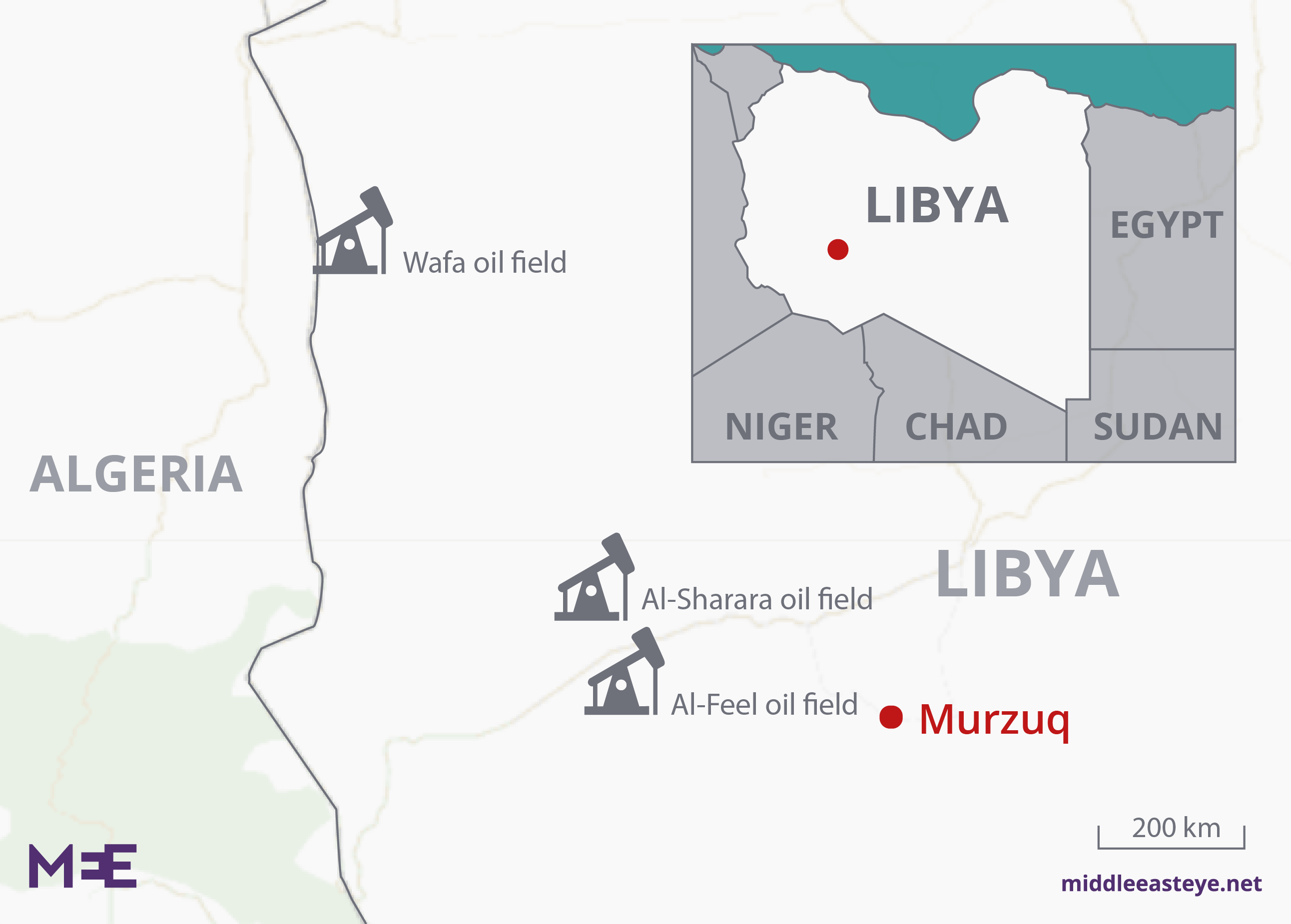

On Thursday, Haftar’s fighters took the strategic town of Murzuq after a two-week assault, boosting the eastern government’s authority in the south.

And then on Friday, the forces seized control of the nearby al-Feel oil field, the second such facility in recent weeks.

The LNA’s gains are a fresh blow to the beleaguered Government of National Accord (GNA), a Tripoli-based, United Nations-backed administration, struggling to assert its authority in the country.

Yet the GNA’s local allies, mostly made up of indigenous Tebu tribesmen, complain that the Tripoli authority has failed to support its southern loyalists.

Following the LNA takeover of Murzaq, they say they have been subjected to extrajudicial killings, lootings and arson.

War crimes

Haftar’s advances have been welcomed by some southern tribes.

But other local communities in Libya’s deepest south have alleged the commander’s forces have been responsible for war crimes in an area long-neglected by a series of failing governments vying for power.

Mohamed Adem Lino, a Tebu MP from Libya’s eastern authority, told Middle East Eye that at least 17 civilians in Murzuq had been killed during clashes and by LNA air strikes.

'Up to 90 houses have been torched and 104 cars belonging to Tebu have been stolen'

- Mohamed Adem Lino, a Tebu MP

The town’s defenders have also suffered losses. Ibraheem Mohamed Karray, who the GNA appointed to lead its allies in Murzuq, was assassinated by an unknown group last week.

Meanwhile, an unknown number of Tebu fighters were killed attempting to keep LNA forces at bay.

According to Lino, Haftar’s fighters turned to looting and arson once they entered the town.

“Up to 90 houses have been torched and 104 cars belonging to Tebu have been stolen,” he told MEE. “My own house and my brother’s house were among the homes burned down.”

Murzuq residents told MEE that Tebu-owned properties are routinely being ransacked before being set ablaze, while militias are raiding the homes of known Tebu officials and social media activists.

“They broke into our house, demanding my elderly father tell them my whereabouts, and they threatened my family only because I had spoken to the media,’’ said one Tebu social media activist, speaking on condition of anonymity from Tripoli where, fearing for his life, he is now in hiding.

Another Murzuq resident, Haithem*, told MEE: “No one in the world knows what is really happening inside Murzuq now because there’s no freedom of speech and no independent press or TV.”

“We are in a critical situation and there is no media to carry our voice outside,” he added.

“We watch Libyan TV - where each station has its own biased agenda - and they don’t say the truth, they just show the LNA celebrating and saying ‘we have liberated Murzuq and there is now security and freedom’. But it’s not true. We are not okay and we do not have freedom.”

In pro-eastern government media, the LNA has made pains to say it does not discriminate against the Tebu, whose fighters comprise the main resistance their forces have encountered in the south.

However, Haithem said this did not reflect people’s experiences on the ground.

Local resident Mahmoud said LNA forces withdrew from the town centre at night, fearing ambush attacks, but returned each morning, bringing with them fresh waves of violence.

“During the night it’s OK, but in the morning they come back inside and the shooting starts again,” he said. Much of the gunfire is not of a celebratory nature.

“No one can move now in Murzuq. There are serious food shortages and everyone is locked inside their homes in terror but the LNA forces break down doors and enter anyway, and they take anything and everything they can find, including telephones and even clothes,” said Mahmoud.

All this has left him terrified to even step outside, and he says he hasn’t left his house in four days.

Almost no one in the south will now allow the press to use their real names, fearing retribution.

One local journalist said his own fears had stopped him from working or even talking to local media.

'I feel I have returned to the horrible times in 2006 and 2007 when the Gaddafi regime was completely intolerant of any kind of freedom of expression'

- Local journalist

“How undemocratic and humiliating this is for us,” the journalist told MEE.

“I feel I have returned to the horrible times in 2006 and 2007 when the Gaddafi regime was completely intolerant of any kind of freedom of expression.”

Hassan Kadano, a member of the Murzuq-based Aman Organisation Against Discrimination (AOAD) rights group, told MEE his NGO had accused the LNA of breaching international humanitarian laws and appealed to the UN for urgent intervention to protect civilian lives and help evacuate the wounded.

He added that AOAD was deeply concerned about targeted attacks against civilians and high-level Tebu figures in the town.

Militias and mercenaries

According to Haithem, the LNA’s ranks in the south are full of Sudanese mercenaries who refuse to engage with locals.

“They won’t communicate with us at all. I tried to speak to one of them to ask why they were doing these bad things,” he said.

“I told him we wanted security and if they'd come here to provide security we welcomed them, but he just ignored me and wouldn’t speak.”

Haithem accused the mercenaries of being behind much of the looting in Murzuq, which was echoed by an LNA security source currently stationed in the town and who spoke to MEE on condition of anonymity.

''Mercenaries from Darfur for sure, and possibly also units from Chad, participated in the battle for Murzuq, and they were responsible for looting tens of cars and houses,’’ the source said.

The source told MEE that LNA brigades 155, 115, 128, 106, and 116 led the offensive on Murzuq.

The majority of these brigades are mostly composed of, or commanded by, members of other southern Libyan tribes with longstanding rivalries with Tebu, particularly Brigade 128, led by members of Arab tribe and former Tebu foe Awlad Sulieman.

Previously, Tebu have said they fear rival tribes would use LNA offensives in the south as a cover to advance their own agendas of territorial gains and longstanding vendettas.

Conversely, the LNA has maintained that its presence in the south is intended to secure the area from the presence of terrorists, foreign fighters - including Tebu fighters from neighbouring Chad - and people smugglers.

“Maybe it’s true that in the desert there are mercenaries from Chad, but the [Libyan] Tebu can’t be held responsible for their presence,” said local resident Mohamed.

“Yes, Libya is now full of foreigners from everywhere because there is no border security, but it’s not right that the LNA comes here saying its mission is to protect the Libyan people and then kills us using the term ‘foreigner’ as an excuse.”

Mohamed also claimed LNA ranks were boosted by “thousands” of mercenaries from Sudan, who had surrounded Murzuq, leaving its residents trapped.

Humanitarian crisis

On Saturday, Ghassan Salame, the UN’s special envoy to Libya, received a delegation from Murzuq, including MPs from Libya’s eastern parliament Lino and Rahma Adem, to discuss the security situation and burgeoning humanitarian crisis in the south.

“We briefed Ghassan Salame about the atrocities happening in Murzuq and he promised urgent assistance to secure essential medical and food supplies,” tribal elder Allahuza Mahmoud told MEE.

To date, the UN has mostly only released statements condemning fighting and urging calm.

Now controlling two key southern oil fields, including one of Libya’s largest - al-Sharara, currently under force majeure - the LNA appears to have set its sights on a third.

On Sunday, the LNA advanced towards Wafa oil field in the Ghadames basin, a joint venture between the Libyan National Oil Corporation and Italian oil and gas giant ENI.

Following negotiations, the handover of al-Feel was largely peaceful.

A field engineer told the Reuters news agency that oil production had remained unaffected and said there had been no clashes at the field.

However, local resident Mahmoud told MEE that, although technically a peaceful handover, three Tebu oil field guards were killed when leaving al-Feel and another two were apprehended.

“In the media the LNA spoke about the two men they captured but they didn’t mention they’d also killed people, and I know for sure because I know one of the dead,” Mahmoud said.

“They had no heavy weapons, just small arms, because they were at al-Feel to provide security not [to] engage in battles.”

LNA forces are also reportedly preparing for further advances south towards the Tebu towns of Um Aranib and Qatroun, Libya’s central-southernmost town.

Locals say Tebu militias in these towns are unlikely to put up much resistance, fearing a similar fate to Murzuq.

“What’s happening in the south now symbolises deep disappointment for Tebu because it’s taking us back to the Gaddafi-era when we were severely marginalised,” said local resident Ahmed.

“It has dashed Tebu hopes that, after 2011, we could live with equality and safety in a diverse and multicultural Libya. Instead, we are now watching these hopes fade away before our eyes.”

*Some names have been changed to preserve anonymity

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].