In a corner of Cairo, this Nubian group creates the sound of home

It was a relatively chilly evening in the Egyptian capital Cairo as the Aragide Nubian troupe took to the stage. But the cold outside was quickly forgotten.

'Aragide is a way of life rather than just an art'

- Farah El-Masry

From their first song, the enthusiastic audience reacted with warmth and joined in, clapping to the percussive melodies, while people danced to the tempo of the beating drums.

Aragide, which refers to the word “joy” in the Nubian language, is one of the last remaining groups in Egypt attempting to revive the distinctive art of singing in Nubia’s “Fedija” language.

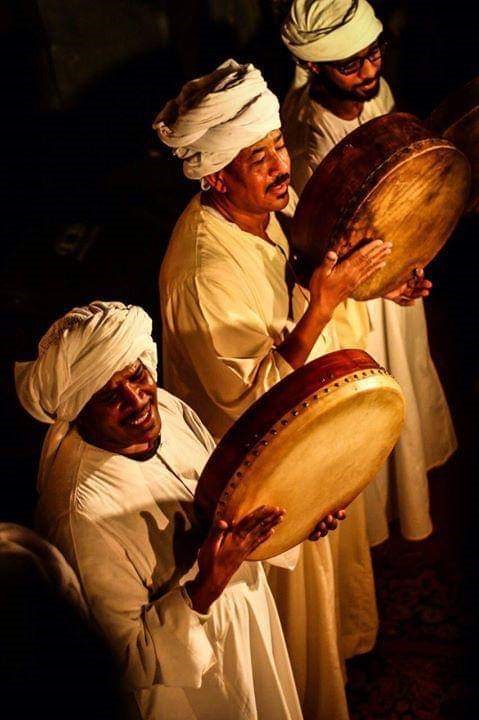

The group is one of the few active ensembles playing the traditional music of old Nubia, which depends on only two instruments: the voice of the band’s vocalists and the duff (a large oriental frame drum).

Aragide's name reflects the feelings and spirit of its audiences, who rarely stop applauding throughout the performance.

The name is also symbolic of the music played during traditional weddings of the Fedija tribe.

“Aragide is the art of Nubian dancing performed during weddings and other local festivals,” said Dr Mostafa Abdel-Kader, a researcher of Nubian heritage.

The enthusiastic applause and the deep, strong voice of bandleader and co-founder, Farah El-Masry, while he taps on the duff and sways to the rhythm, add to the general mood of the show.

The group performs their art wearing jallabiyas, traditional robes. Some, including El-Masry, wear the entire traditional outfit with the Nubian turban.

Their voices are only accompanied by the duff.

“We imitate the tradition of Aragide in Nubia where we sing only to the duff without any other instruments,” El-Masry explained.

“We sing both songs from our heritage and others written by old and contemporary Nubian poets,” he said.

El-Masry sports a moustache and has a kind, ageless face; he won't say how old he is as he has superstitious beliefs that this will bring him bad luck, or more precisely: the evil eye.

“It is enough to say that I have been singing since I was eight…and that I moved to Cairo and started my singing career during the 1980s,” he said.

“My true name is Mohamed. But people in my Nubian village nicknamed me Farah [joy] because I love singing very much and I was singing all the time in all of our occasions,” he recalled.

Distinctive music

Nubian music is distinguished from other Egyptian styles by its use of the pentatonic scale. A heavy drum and a normally fast tempo make Nubian music festive and exciting, while repetitive chants are usually the most common vocals in Nubian singing.

“The Nubian music is known for its African tempo which usually urges whoever listens to it to dance,” Abdel-Kader said.

Audiences usually take part in Aragide performances by dancing with the group, creating a sense of unity.

"Aragide is a way of life rather than just an art. Our whole life as Nubians is Aragide. Singing and dancing is part of who we are. We sing to love, compassion, the harvest season and the Nile River,” El-Masry explained.

Aragide’s audiences come from different age groups and nationalities.

“I can’t understand the Nubian language, yet I feel that the songs are quite inspiring and joyful. I can’t explain it. But this is how I feel about it,” said Ahmed Hassan, a 50-year-old school teacher.

'I can’t understand the Nubian language, yet I feel that the songs are quite inspiring and joyful'

- Ahmed Hassan

Nancy Hall, a 29-year old British national, shares Hassan’s view. “It’s as if my heart is dancing to the tempo,” she said.

The group has been performing regularly at the Egyptian Centre for Culture and Arts, or Makan, without microphones or a sound system, which adds to the authentic nature of the band's shows.

“Singers nowadays use a sound system in the era of technology. What is challenging for us is that we sing live without any sound equipment, not even microphones,” El-Masry said.

Since the group was first founded in 2003, Aragide has performed in Belgium, Germany, Japan and a number of Gulf countries.

Legacy at risk

The Nubian legacy is at risk of dying out as Nubians younger than 60 years of age have forgotten the ancient songs.

Those who still remember the songs are no longer sought after to perform.

“I am currently the only remaining artist singing Aragide songs. We are attempting to restore this art, but it is a tough job,” El-Masry said.

“Nobody in the younger generations knows the songs because they are not written. They are transferred orally. For example, my son only hears the Nubian language at home. But because we are living in Cairo, he can’t hear it anywhere else,” he added.

Marginalised in their homeland

El-Masry argues that Nubian art is marginalised in Egypt and says that official support for the music is not administered by people who understand and know the culture.

“The state officials don’t assign the few initiatives or projects that have to do with Nubian arts to real Nubians who know well about our arts and culture. Those in charge have nothing to do with Nubia,” El-Masry insisted.

“We as Nubian artists are usually ignored by the Egyptian media. Egyptian satellite broadcasters rarely interview Nubian singers or present them performing for Tiba broadcast from Aswan,” he said, referring to an Egyptian satellite TV channel targeting the residents of Upper Egypt.

The ties of Egyptians to Nubian music are relatively weak, says El-Masry's son, Alaa.

“It has to do with cultural differences. People feel that our language is hard to understand. Also, musically speaking, Egyptians are not quite familiar with the pentatonic scale except for upper Egyptians,” said Alaa, who is also a member of the Aragide troupe.

Nubia is an Egyptian region that lies along the Nile River. It encompasses the area between Aswan in southern Egypt and Khartoum in central Sudan.

Nubia is characterised by its rituals and the traditions of the Kenouz and the Fedija tribes, the two main language groups in Nubia.

Tough experience

It was the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1963 that caused the total flooding of Nubian lands. It brought distinct groups of Nubians together as permanent exiles from their homeland, in what is known as “communities of memory”.

“Nubian traditions have been affected by the traumatic experience of displacement and the disappearance of their natural environment, which was a main inspiration for their musical culture,” Abdel-Kader said.

El-Masry agrees with Abdel-Kader.

"Nubians suddenly found themselves living in the mountains instead of their old lives where they were surrounded by natural scenery, which had a negative impact on their arts,” El-Masry said.

As the performance reaches a crescendo, with the band members and audience dancing together in the intimate space at Makan, it feels as if this small venue in Cairo is a living piece of Nubia.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].