British foreign policy in the Middle East: A secret history of self interest

On Tuesday in the British parliament, Labour's shadow foreign secretary Emily Thornberry asked an urgent question relating to allegations that British troops have been covertly fighting in Yemen and supporting the Saudi-led coalition.

As reported in the Mail on Sunday, five British special forces troops from the elite Special Boat Service (SBS) were injured while "advising" Saudi Arabia on their deadly campaign in Yemen.

The commandos were injured in gun fights as part of a top-secret campaign, and other reports have claimed British troops have been killed in such battles. British soldiers from the Special Air Service (SAS) have reportedly been secretly deployed and operate "dressed in Arab clothing".

Responding to Labour's questions Mark Field, a minister in the UK's foreign office, said that he would seek to get to the bottom of these "very serious and well sourced" allegations.

The presence of British soldiers in Yemen, secretly fighting a war that has brought death, famine and destruction to millions of innocent civilians raises an age-old question: why does British foreign policy in the Middle East support dictatorships, abuse human rights and prioritise Britain's power status?

It's tempting to say the reasons are simply geopolitics, oil and other commercial interests. But there is a deeper explanation: Britain, far from being a true democracy, is in reality an oligarchy that promotes the interests of a privileged domestic elite. The idea that Westminster is the "mother of all parliaments," representing a democratic model for the world, is a cultivated myth.

The UK has elections every five years, an independent judiciary, freedom of speech and association, and strong laws protecting the equality of all citizens and civil liberties. Yet real power rests in the hands of an elite few who control policy-making institutions and the dominant ideas in society.

British foreign policy-making is so centralised that it is akin to an authoritarian regime. A prime minister can send troops into action without even consulting parliament.

Britain is currently fighting several covert wars with no parliamentary authorisation or debate. Away from Yemen, special forces are operating on the ground in Syria, despite parliament only having approved air strikes against the Islamic State (IS) group. The British covert war in Syria has been going on since 2011, with almost no discussion by elected MPs.

Even when asked parliamentary questions on overt foreign policy, ministerial responses are invariably minimalist, and often misleading or deceitful

In 1976, Lord Hailsham famously termed the UK an "elective dictatorship" because parliament is easily dominated by the government of the day which faces few constraints on its power. But this was before former prime minister Margaret Thatcher centralised decision-making still further, regularly bypassing the cabinet and relying on a small set of advisers – a strategy continued by Tony Blair, leading to the disastrous invasion of Iraq.

While the government is saying it will look into the role the British military is playing in Yemen, the stock response to parliamentary questions on UK covert action tends to be: "For reasons of national security, it is the longstanding policy of successive British governments not to comment on intelligence and sensitive operations."

Even minor information is withheld on "sensitive" subjects: when MP Alex Sobel asked the government last month how much the US government reimburses Britain for the costs of the defence ministry police at the spy base at Menwith Hill in Yorkshire, a government minister refused to say.

Even when asked parliamentary questions on overt foreign policy, ministerial responses tend to be minimalist, and are often misleading or deceitful. Anyone who has made a Freedom of Information request to the government will know that they are routinely denied on the pretext of protecting "national security".

Lack of accountability

Neither Blair nor former prime minister David Cameron has been held to account for the disastrous wars in Iraq or Libya. The British political system is so extreme that no minister has, to my knowledge, been held to account for crimes abroad – despite numerous wars, covert operations, coups and involvement in human rights abuses.

In Yemen, the UK-supported Saudi military has for four years been engaged in war crimes, over which British ministers have acted with impunity.

Government policies are meant to be scrutinised by all-party parliamentary committees, but they rarely hold the government to account. They tend to be packed with government supporters who fail to investigate key policies or grill ministers.

Mainstream media amplification

In the UK's "mainstream" media, many key British foreign policies are not covered at all. There are perilously few articles reporting the extent of UK support for Israel or the Sisi regime in Egypt.

Even the war in Yemen has been little scrutinised; there is criticism of UK arms exports, but little if any mention of the air force maintaining Saudi warplanes and storing and issuing the bombs for their use. The Mail on Sunday's report on covert British action in Yemen is a revelation partly because such coverage is so infrequent.

Although mainstream articles do reveal aspects of UK foreign policy, it is more typical for reporting and commentary to amplify the policies of the state or to spread disinformation. False assumptions pervade the media, such as that UK policy in the Middle East is based on support for democracy and human rights.

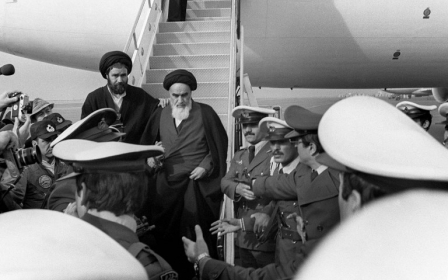

The 1953 Anglo-American coup in Iran was about maintaining the interests of oil firms – in Britain's case, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Corporation, the forerunner of BP. Fifty years later, the 2003 invasion of Iraq was also mainly about oil, as was the 2011 war in Libya.

The UK's support of Egypt's Sisi regime appears to be mainly about oil and gas interests in the country. The special relationship with Saudi Arabia seeks to promote BAE Systems and other large arms corporations.

The extensive revolving door of personnel between government and corporations plays a key role in ensuring that elite interests are aligned. David Omand, the former GCHQ director, went on to work for the arms corporation Babcock; General David Richards, the former army chief of staff, was tapped to chair the UK advisory board of the US arms corporation DynCorp; and John Sawers, the former director of MI6, was appointed a non-executive director of BP, among other examples.

More a club than a country?

In some ways, Britain resembles more a private club than a country. As author Adam Ramsay has noted, only five British universities have produced a prime minister, and more than twice as many have gone to Eton as to non-fee paying schools.

It is striking that there have been so few whistle-blowers revealing secrets about UK foreign policy. This is probably because those allowed access to the elite normally come from the same circles and can be relied on to be one of the chaps forever.

The main challenger to traditional UK foreign policies – Jeremy Corbyn – is being attacked and undermined on all sides

The very top of the UK’s privilege system – members of the royal family – are regularly deployed by the foreign office and ministry of defence to support UK policy and military interests abroad.

Royal visits help to build relations with key regimes and sell more arms to the Middle East. The system is built on patronage, highlighted by the House of Lords, a medieval anachronism that is packed full of appointees of the government.

There are few signs that British oligarchy will change anytime soon. The "permanent government" in Whitehall is deeply entrenched. The main challenger to traditional UK foreign policies – Jeremy Corbyn – is being attacked and undermined on all sides. But it is not clear that even Corbyn intends to challenge British oligarchy.

There is a real need for a transformation away from centralised, unaccountable governance to a system that is much more participatory, and where citizens are informed and empowered, something that would change both domestic and foreign policies. This would benefit not only Britons, but the Middle Easterners on the receiving end of British policies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].