'A void no one can fill': Gaza's children face trauma of losing friends, family in protests

Wassal Sheikh Khalil, 14, knew she was going to die.

On 13 May, she told her mother over dinner: "Today is my last day of school, and the last day I have dinner with you.

"They will shoot me in the head," Reem Abu Irmana remembers her daughter saying. "I won't feel it, or feel the pain."

The next day, as tens of thousands of Palestinians protested in Gaza to denounce the US embassy to Israel's move from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the teenage girl’s eerie prediction became true.

While standing in the middle of a crowd of women and children with her younger brother Mohammed, Wassal was shot in the head by an Israeli sniper. Another demonstrator was filming when she was hit, her body slumping forward to the ground.

She was among 68 Palestinians to be killed that day.

According to the UN Independent Commission of Inquiry and other human rights groups, Israeli forces have killed at least 40 children in the context of the Great March of Return since 30 March 2018.

At least 32 were killed by live ammunition or shrapnel. According to the commission, another 1,642 children have been injured by live ammunition, shrapnel, rubber-coated steel bullets and direct tear gas canister hits.

In the small sliver of land that is Gaza, where half of the population is under 18, many children do not remember a time before the 11-year Israeli blockade. Most have already lived through three devastating wars.

Hundreds of thousands were born refugees and have never seen the villages from which their families were expelled during the creation of the state of Israel.

Growing up in desperate conditions, for many Palestinians the Great March of Return has symbolised a collective cry for survival.

But one year on, the deadly Israeli military suppression of the demonstrations has become yet another traumatic experience for Gaza's children. Unicef estimates that more than 25,000 children are in dire need of psychosocial support.

The march of life and death

Wassal lived in al-Maghazi refugee camp in the central Gaza Strip with her divorced mother and six siblings.

She participated in the Great March of Return since the very beginning with her 12-year-old brother Mohammed.

"We always told her it was a risk, and we were afraid of her being injured," her mother Reem told Middle East Eye.

But the teenage girl would not budge.

On the morning of 14 May, Reem remembers how she forbade Wassal from going to the protest area near the eastern boundary with Israel.

"Wassal was crying, she told me 'I have been waiting for this day for so long, I have to go, I don't want to miss this day'."

For Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, a Palestinian professor who studies the impact of the occupation on children, the Great March of Return awakened in many young Palestinians in Gaza a sense of agency amid otherwise helpless circumstances - even as they are aware of the risks.

Participating in the Great March of Return means a risk of death ... But for children it is perceived as a liberating act to sustain life

- Professor Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian

Speaking at a conference organised by the UK-Palestine Mental Health Network in London earlier this month, Shalhoub-Kevorkian quoted one child in Gaza as saying: "Gaza is not a prison, it is a place with no life. The March of Return is life - but it is also death.

“Participating in the Great March of Return means a risk of death, injury or maiming. But for children it is perceived as a liberating act to sustain life."

As many children, like Wassal, have attended the protests with a feeling of belonging and purpose, the dangerous situation has had a devastating effect on them - not only for those who have been killed, but for those who remain.

Mohammed was standing right besides Wassal when she was shot in front of his eyes.

"She suddenly fell on the ground, the ground was overflowing with her blood, she wasn't moving," the young boy told MEE.

Mohammed and Wassal had always been close due to their small age gap, Reem said of her two children.

After his sister's death, Mohammed came home in shock, she said. He became depressed, violent, lost focus in school, and would often wet his bed - prompting one of the family's neighbours, a psychologist, to start treating the boy as he struggled with his grief.

Even now, Reem says, her son continues talking about Wassal as if she were still here, and will hang pictures of his sister all over the house. In spite of receiving psychological support, most of the symptoms of his trauma remain.

A lost best friend and secret keeper

In Khan Younis, in the southern Gaza Strip, the Shalabis know what Wassal's family has gone through.

On 8 February, Hassan Shalabi, 14, was shot in the chest by Israeli forces while participating in a demonstration.

Less than two months later, the teenager's death leaves a gaping hole in the lives of his relatives and friends.

"I was Hassan's sister, friend and secret keeper," Aseel Shalabi told MEE, struggling to speak of her brother without crying. "Hassan left a huge void no one can fill."

I was Hassan's sister, friend and secret keeper. Hassan left a huge void no one can fill

- Aseel Shalabi

Abdel Fattah Shalabi, one of Hassan's brothers, always slept on the same mattress besides Hassan. As his other family members spoke of his slain brother to MEE, he stood there silently, his eyes filling with tears.

"He [Hassan' suddenly disappeared, it's very hard to adapt without him," said Fatima Shalabi, Hassan's mother.

Fatima and her husband Iyad told MEE that their children were severely affected by the loss, struggling with nightmares, insomnia and depression.

Four-year-old Ismail Shalabi still does not understand that his older brother is dead, but will often touch photos of Hassan and point to them.

"I try to make my children stronger, telling them Hassan is in a better place," Iyad Shalabi said.

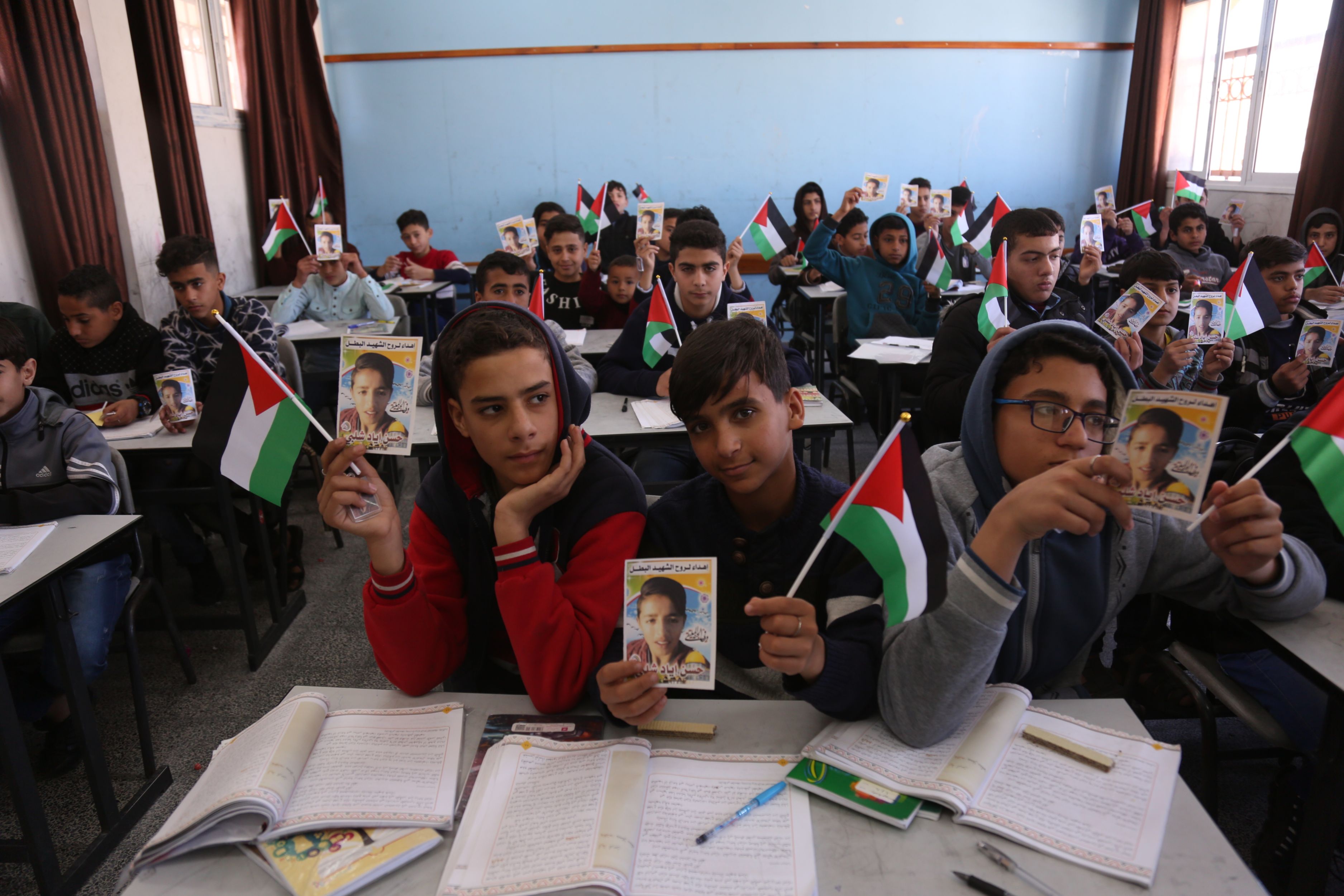

A month after Hassan's death, the boy's classmates are still in shock.

"Hassan is not only my best friend, he is my soulmate. I spent more time with him than anyone else," 14-year-old Ahmed Abu Qusai told MEE.

"We used to sit on the same seat in the bus on the way to the March every Friday," Ahmed said - except for the fateful day when Hassan was killed, when Ahmed was sick and stayed at home.

Rasmi Abu Sabla, 16, told MEE that he used to play football with Hassan, Ahmed, and other boys in the neighbourhood every day.

"Football games are not the same," he said. "Hassan was best player, and football is not football anymore after his death."

An emotionally damaged generation

According to the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), the Great March of Return has created tremendous levels of distress among children in Gaza.

In a report published earlier this week, NRC reported that young children are experiencing high levels of distress due to losing family members.

Dr Sami Oweida, a psychiatric consultant in the Gaza Community Mental Health Programme, told MEE that many children have experienced bedwetting, low academic achievement, nightmares, fear and anxiety since the beginning of the Great March of Return.

"Palestinian children have the highest rates of mental disorders among all Middle East countries," Oweida told MEE.

Dr Samah Jabr - a Palestinian psychiatrist who, like Shalhoub-Kevorkian, spoke at the "Palestinian childhoods" conference in London - warned against divorcing the psychological diagnoses of Palestinian children from the political context.

"The occupation ... affects children's perspectives about themselves, about the world, about their relationships," she told MEE. "It creates psychological morbidity that goes beyond the official labels that we know in psychiatry.

"We need to talk about things differently than trying to put Palestinians' experience into the usual framework of individual psychopathology.

"We need to really be discussing empowerment, representation, creating role models - things that help Palestinians step out of their status as objects and pathologised individuals and help them reclaim their agency."

NRC Palestine country director Kate O'Rourke also stressed the fundamental importance of addressing the political context when dealing with the psychological scars borne by Palestinian children in Gaza.

"The violence children witness daily, including the loss of loved ones, in the context of Israel’s crippling siege, which perpetuates and exacerbates Gaza's humanitarian crisis, has left an entire generation emotionally damaged," she told MEE.

"It takes years of work with these children to undo the impact of trauma and restore their sense of hope for the future.

"Gaza, like the rest of the occupied Palestinian territory, desperately needs a just and lasting political solution - including for Palestine refugees - which places the lives, welfare and dignity of both Palestinians and Israelis at its centre," she added.

But with no political solution in sight, Gaza's children are left with only bandaids to address their grief and trauma - as families hold on to personal rituals and symbols to help process their loss.

Every week, the Shalabi family will go to the cemetery and visit Hassan's grave. They believe the flowers they lay by his tombstone will make him happy, and maintain that even though his body is gone, his soul will never leave.

Chloé Benoist contributed reporting from London.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].