‘We are the flood’: The Algerian artists voicing the protest movement

After six weeks of peaceful protests that swept Algeria, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika has resigned, fulfilling the first demand of the demonstrators.

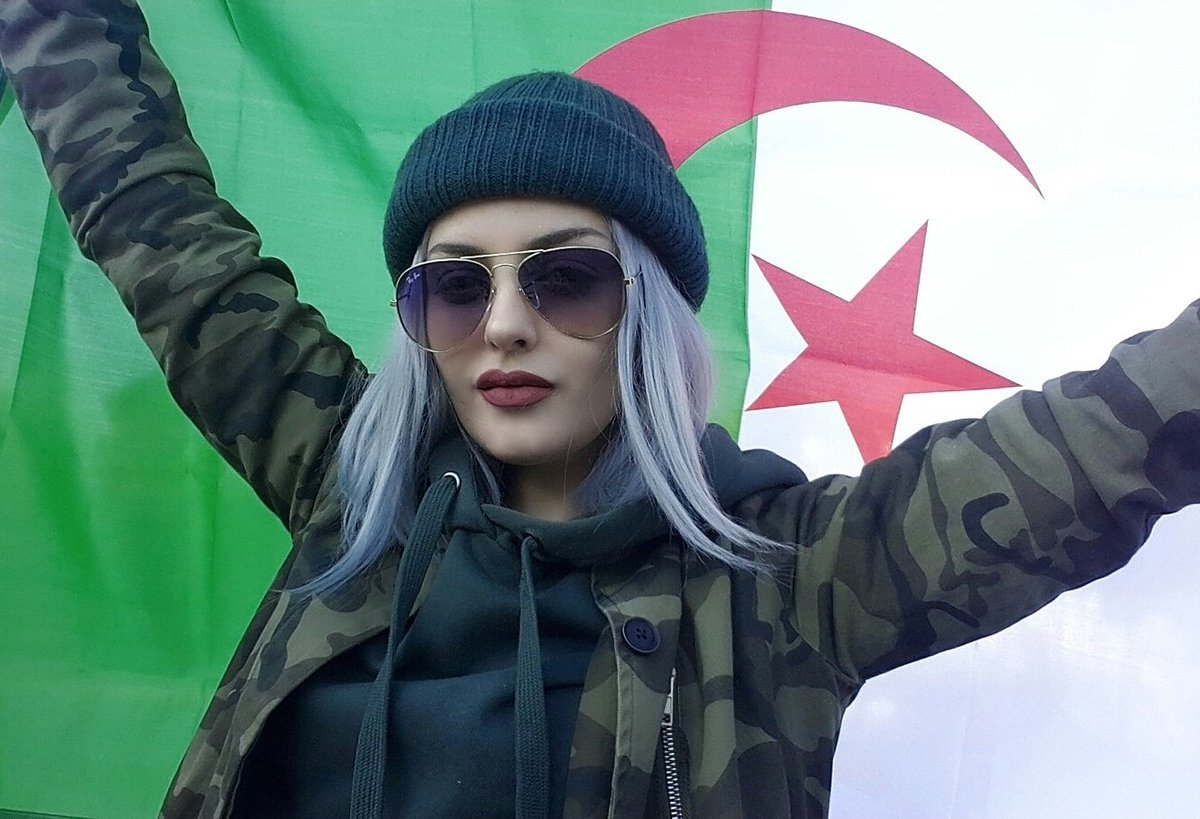

Many of those who have taken to the streets since 22 February have repeated the words of popular anthems, such as Soolking's Freedom, or shared images that have captured the spirit of unity on the street.

Male and female artists are demonstrating against the system and for their country through their art. Middle East Eye profiles seven of the artists and their work, who together reveal the current state of mind of Algeria.

“Freedom, freedom, freedom, it is first in our hearts.” These words are tagged on the country’s walls and shouted in chorus during the protests, reflecting a vibrant national unity. They are taken from Liberté (Freedom), a song by the Algerian rapper Soolking. Posted on YouTube on 14 March, three weeks after the beginning of the protests against President Bouteflika and the corrupt political system, it has so far had more than 44 million views.

It has gained so much popularity among the largely young population that it is considered a hymn of the revolution. Soolking, 29, was already famous in Algeria when he captured with his soft music and lyrics the pacifist spirit of a movement that has been widely praised for peaceful protests and the avoidance of violence.

A young woman in a hoodie makes a call on a graffiti-scrawled payphone in a drab urban passageway. It is the opening of the video for Raja Meziane’s fierce and direct protest song Allo le Système. “This idea of calling the system is haunting me,” said Meziane, 30, in a phone interview from Prague, where she lives today.

“I always wonder why our people can’t express themselves.” In her video, which has had more than 16 million views, she calls the system - which she describes as “a gang of scammers” - from a payphone, though nobody answers. Her lines are powerful (“You have buried us alive and left the dead in power”) with a chorus of the people's demands: “We want a republic; People's democracy; Not a monarchy.”

The singer, known to be politically engaged, had to leave Algeria in 2015 because of censorship that prevented her from working. She wanted to support Algerians with her “cry of anger” in music, rather than a speech. “With a song, there is an artistic work that attracts attention,” she said. “It gives people chills.”

Libérez l’Algérie (Release Algeria) is a song by a collective - composed of more than 40 artists, including singers Amine Chibane and Amel Zen - willing to support the popular movement and freedom of speech. They released it on 1 March as an urgent initiative to take part in the protests through music.

The song ingeniously mirrors the country with the use of its various dialects that display its diverse but united communities. And the message, to “liberate Algeria”, is a historic call of the ongoing battle of the population.

A dancer holds an Arabesque pose in the midst of a protest on the street in Algiers; quickly, the image goes viral and is shared by millions. “Poetic protests” is performed by dancer and model Melissa Ziad, and shot by photographer Rania G.

Captured on 1 March, it has touched people all over the world with the gracefulness of the movement, the implied empowerment of youth and women, and the confidence of the people in their victory.

The photographer told MEE: "'Poetic Protest' symbolises for me poetry, freedom and lightness, just like this slender posture upwards. Because my hope for this protest movement is that it will pull us all up."

Due to a recent operation, MYA Mounia Lazali, 42, a professional painter based in Algiers, is unable to walk with everybody during the regular Friday demonstrations. Instead, she does what she always does to express herself: she paints. “I wanted to paint this popular energy,” she said in a phone interview. “So when you look at the painting, you feel what it’s like when you are in the streets”.

Her first painting is entitled #silMYA (pacifism), as this word became a slogan and a hashtag for the revolution. It is also a nod to her artistic name. Lazali painted two other works at the same time and shared them on social media.

While they are already booked by private collectors, what moved her were people's reactions. “They said they recognised themselves in my paintings, it’s truly rewarding,” she said, as she defines the artist as the messenger of the people who “condenses emotions, channels it into the beauty and creation, to participate at the writing of history”.

Houari Bouchenak, 37, who is based in Tlemcen in the northwest of Algeria, does not miss a protest. With his camera, he captures the faces, emotions and the energy of the crowd during the demonstrations. “It’s like our history has always been hidden, or transformed,” he said in a phone interview. “So it is a way to leave traces and demonstrate, through photography.”

His images capture something ephemeral in this moment of unpredictable change in the country, as illustrated in the metaphorical power of the above photo: “There is the flag, the light, but we can’t see entirely, and silhouettes of people, who are not yet into the light,” he said. “To me, it represents the optimism of people at the moment, and the blurry transitional time that we are living and in which we are not out yet.”

When Saad Benkhelif saw people marching and holding his cartoon on the streets, it was a heartwarming moment for the satirical cartoonist. “It means the message has passed,” said the 37-year-old, who works at the leading independent daily newspaper El Watan. Like many, he was outraged by Bouteflika’s running for a fifth mandate, and drawing was a visceral and militant need. “It’s like my pen, my sheet of paper are calling me,” he said in a phone interview.

He wants to make people think through the incisive satire and analysis that only a cartoon can offer. “A picture is worth a thousand words,” he said.

For example, in the above cartoon, we see the head of the army apparently about to drop the president off a cliff, with the number 102 shown on the plank, in reference to the constitutional article that could see Bouteflika retired due to his poor health. The implication is that the army is still controlling events.

Recent movies like Sofia Djama's The Blessed (2017), or Karim Moussaoui's Until the Birds Return (2017) provide an insight into the sorrows, traumas and hopes of Algeria. “In my film, I talked about the difficulties to move to something else,” said Moussaoui, 43, in a phone interview. “To go towards an inner revolution, so that it materialises in a global revolution.” This is what is happening now in Algeria.

This image, whose creator is unknown, features the empty picture frame that protesters see as representing the ailing president. Instead of an octogenarian whose time has run out, it is now the mass crowd of ordinary Algerians who have filled the frame.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].