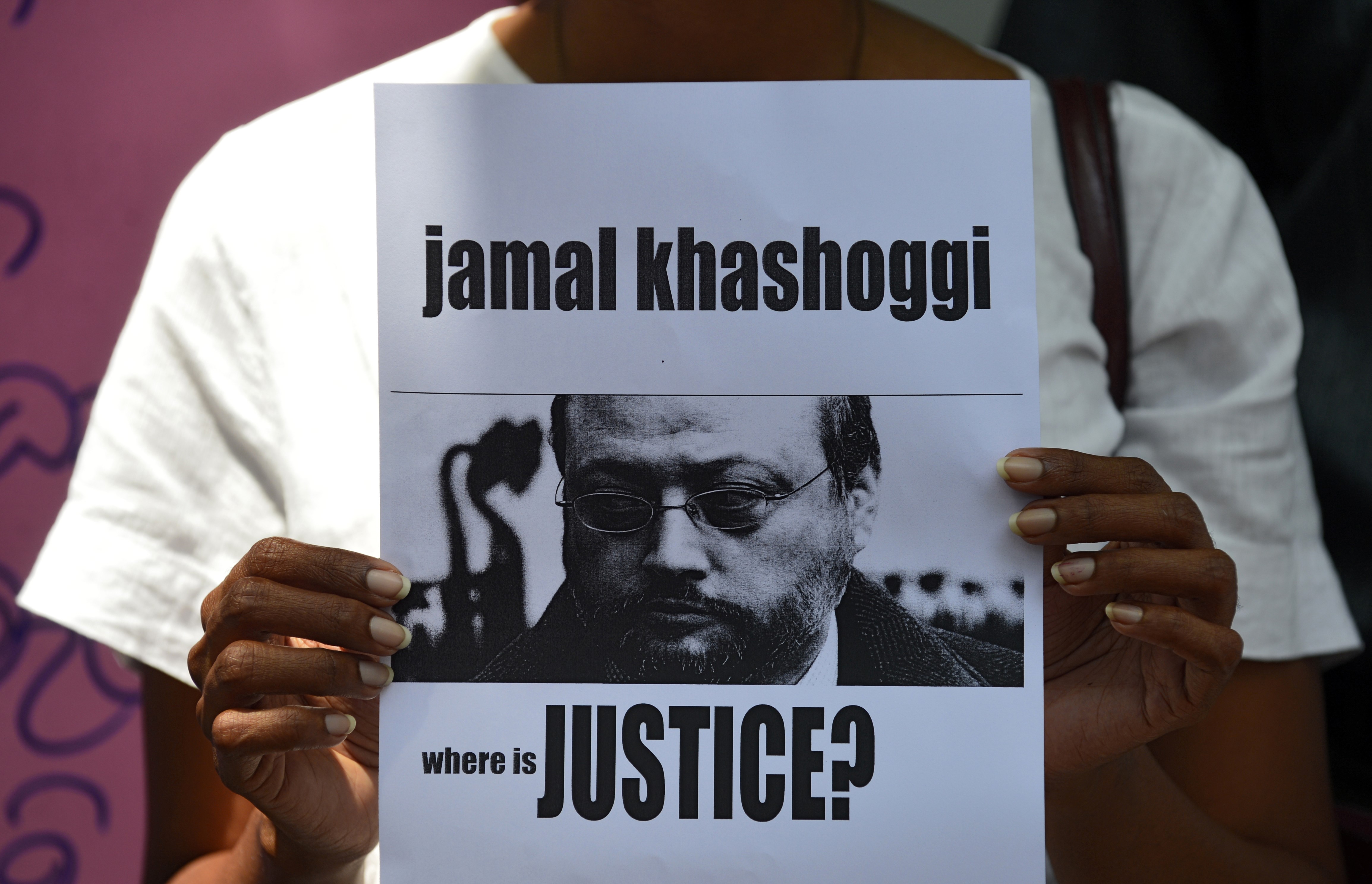

Six months on: How Jamal Khashoggi's death changed Saudi Arabia forever

Six months have passed since Jamal Khashoggi walked into the Saudi consulate in Istanbul and never came out.

Every new gruesome detail of the pop-up abattoir that Khashoggi strode into - and there are more to come - of the Tiger Squad that organised his and other dissidents' deaths, of the cover up and the denials, has deepened the crisis for Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, who is believed to have ordered Khashoggi's killing

A prince, who fashioned and cultivated his rise to the Saudi throne in the Western media, now finds himself painted as its number one monster.

In six months, bin Salman has gone from reformer to despot, from the keystone of efforts to create a "moderate Islamic" leadership of the Sunni Arab world to the region's single greatest source of instability.

In six months, Mohammad bin Salman,who cultivated his rise to the Saudi throne in the western media, now finds himself painted as its number one monster

To take one measure of the distance bin Salman's image has travelled in this period, it is worth re-reading the interview he gave to six of Bloomberg's finest and brightest journalists days after the murder in the consulate.

Khashoggi's disappearance was treated by Bloomberg as an afterthought to the much more relevant story about the Aramco IPO, or plans to invest $45bn in Softbank.

The crown prince was allowed to get away with a straight-out lie: "We hear the rumors about what happened. He's a Saudi citizen and we are very keen to know what happened to him. And we will continue our dialogue with the Turkish government to see what happened to Jamal there," he said.

That such journalism is impossible to read today without laughing is a measure of the indelible stain Khashoggi's blood had made on bin Salman, a stain no amount of money or public relations can wash off.

The good, the bad, the ugly

To be seen today to be in the pocket of the Saudis is toxic for your brand, as the Financial Times, Softbank, JP Morgan, Credit Suisse and a host of executives who dropped out of the Future Investment Initiative, dubbed Davos in the Desert, have all discovered.

Past encomia of the prince by the likes of Tom Friedman of the New York Times, David Ignatius of the Washington Post, the BBC's Frank Gardner, The Guardian, The Times, have had to be speedily retro-fitted, Friedman "revealing" that one of the sources for his columns was in fact Khashoggi.

Of course, the gap between the Western view of the good, the bad and the ugly in the region and reality has always been uncomfortably large, which is why websites like Middle East Eye are needed.

To the Saudis themselves, Khashoggi's murder came as little surprise.

It was a full year after the arrests of Muslim scholars, Shia activists, and more than 365 members of the royal court and business elite in the Ritz Carlton. Bin Salman had the business elite arrested and some tortured not because they were any less corrupt than he or his father had been, but simply because they were in his way. He needed their assets. The Ritz Carlton shake-down continues to this day. Those released from prison are still not free to travel and resume their business interests.

The Muslim scholars represented a political danger to the crown prince, because, like Khashoggi, they were pro-reform moderates. When your legitimacy depends on Western backing, that is the pathological conclusion you come to. It is power, not reform, that bin Salman has from day one targeted.

So the first reaction of regime loyalists was to actually boast about Khashoggi's death. His was a big scalp: "You leave your country arrogantly … we return you humiliated," Faisal al-Shahrani tweeted. Prince Khalid bin Abdullah al-Saud sent a message to another Saudi dissident: "Don't you want to pass by the Saudi embassy? They want to talk to you face to face."

Distance and distract

Perhaps it was because he had got away with so much already without so much as a rap over the knuckles that the reaction to Khashoggi's murder came as a bolt of lightning to the young prince.

To this day, he is struggling to find strategies to contain it. His first thought was to buy off the Turks. He personally called a senior figure in Turkish intelligence to invite him to Riyadh where he said: "This can be sorted out in an afternoon." The man refused. So too did Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

The twin strategy of Mohammad bin Salman has been to distance himself from the events he himself put in train and to distract

As the enormity of the crime grew, King Salman despatched his counsellor Prince Khaled al-Faisal to Ankara. Al-Faisal dangled a series of offers in his meeting with Erdogan: Saudi could help Turkey with investments. It could buy Turkish weapons.

Erdogan cut him off in mid-flow, according to an informed source. "Are you trying to bribe me?" he asked outright. Prince Khaled was allowed to listen to the 15-minute tape of Khashoggi's murder. He returned with a sense of failure.

Ever since, the twin strategy of bin Salman has been to distance himself from the events he himself put in train and to distract.

The claim he did not know about a murder arranged by the death squad he personally set up was always going to be doomed from the start. A discreet disappearance of a Saudi national on Saudi consulate property ended up being the most recorded and publicly documented crime in recent history.

There is simply too much evidence pointing at him.

The father, the son

The CIA's Gina Haspell not only took the evidence recorded by the Turks but added to it from America's global surveillance gathering. Mohammad Bin Salman can take on and crush his more experienced cousin Mohammed bin Nayef, but even he knows he cannot take on the CIA and win. His only remaining insurance is Donald Trump himself, and that policy might expire.

However, he keeps on trying. The latest of his efforts is a series of leaks in The Guardian which purport to claim the king is taking back control of events from his son. Medical reports detailing torture and abuse of detainees have been passed to the king with a view to him issuing a pardon, the paper reported.

There is only one source of power in the kingdom, but there are two symbols of it. The King thus performs the function of the son's dummy

This is a tried and tested device by the son’'s inner circle. The king himself is suffering from dementia. He finds reading a speech prepared for him difficult, as his performance in the latest Sharm el Sheikh summit revealed.

He cannot answer questions, as his private conversation with Erdogan after the Khashoggi murder revealed. He is as much a prisoner of his son as everyone else is.

Access to him is controlled by Mohammad bin Salman's bodyguards, and even an old friend he likes to play cards with is denied access. That such a king, in such a condition, is in a position to question his son, who has seized total control of the country, is open to doubt.

However, the king, while he is still alive, remains the son's sole source of legitimacy. So he has become instead a device. When Mohammad bin Salman realised he had gone too far in underwriting US President Donald Trump's Palestine-related "Deal of the Century," and the withdrawal of East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state, the Palestinian file was reported to have been retrieved by the king. The same formula was used over the failure of attempts to launch the IPO of Aramco.

There is only one source of power in the kingdom, but there are two symbols of it. King thus performs the function of the son's dummy.

The network

The other tactic to regain ground lost by Khashoggi's killing is to distract. As I reported, a series of ideas have been floated by the emergency committee set up by the crown prince to deal with the Khashoggi crisis.

One of these was to arrange a Camp David style handshake with Israeli Premier Benjamin Netanyahu - an event calculated to get bipartisan support on Capitol Hill and position the prince as Middle East peacemaker.

This again has got nowhere. Instead, more and more details have been revealed about the network that launched bin Salman on the world stage, the same network that was used to allegedly hack the phone of Jeff Bezos, the CEO of Amazon.

This bears the same message. The prince, who was sold six months ago as the new order in the Middle East, is the disrupter of order wherever that happens to be.

Reality sinks in

Stripped of Western support, the hype, the money, and the image, the reality of life under Mohammad bin Salman is starting to sink in, especially to the youth who supported him.

As Khashoggi told me: "The youth will support MBS until they have to start opening their wallets. Then it will not matter how many cinemas they are allowed to go to." That is now starting to happen.

With the oil price stuck, the kingdom has to issue a further $31.5bn in debt to finance the budget deficit, on top of the $150bn of debt outstanding from last year.

Attempts to diversify the oil dependant economy are all running into the sands. One million foreign workers have left after two taxes were introduced to open up the labour market to Saudis.

But that has not happened. Instead firms are trying to disguise their foreign workers by registering them under Saudi names, a practice which the kingdom has had to condemn by resorting to the medium of imams' sermons at Friday prayers. Using imams to issue government warnings to business has in turn shocked the religious.

Privatisation is not working. King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center is one of the jewels in the crown of the Saudi health service. It is one of two hospitals in Riyadh which treated members of the royal household. It was here that the first group of detainees in the Ritz Carlton were treated after they had been tortured.

To cope with its special clientele, its executive supervisor, Dr Kassem al-Qasabi, was housed in a villa with his family in the hospital compound. The hospital was so state of the art that it was earmarked first for privatisation.

The prince, who was sold six months ago as the new order in the Middle East, is the disrupter of order wherever that happens to be

The announcement came as a surprise in the hospital itself. Qasabi was sceptical, but went ahead with the plans. Companies were hired, prices were sought. Suddenly in July 2017 Qasabi was ordered to evacuate his villa and he disappeared. The hospital was left in chaos for several weeks until a caretaker was appointed.

Nothing happens. Then in February, Qasabi reappears as the chairman of the board, by royal decree. All talk of privatisation quietly shelved.

This is how "reform" is conducted in the kingdom. It is more of a merry-go-round where the Saudis find themselves back where they started three years ago.

Washington's contradictory signals

Under this mismanagement, the crown prince is weakening and hollowing out his kingdom. The royal family are angry, resentful and fearful but will not act without a green light from Washington.

It is sending them contradictory signals and nothing has been seen or heard of the king's younger brother Prince Ahmed, an open critic of the 33-year-old prince, since his return.

Jamal Khashoggi was a mild man. He thought of himself as an insider and a loyalist. He hated the thought of being in exile, separated from his family, but he knew it was his fate.

He could never resist a wry smile. In the six months since he died, he has achieved more to change the image of the ruling elite and ultimately lay the foundation for real reforms and public debate about how it is governed than he achieved in the 59 years of his life.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].