The second Arab Spring? Egypt is the litmus test for revolution in the Middle East

In a breathless 48 hours, a president, defence minister and security chief have all been ousted in Sudan.

Omar al-Bashir held absolute power for three decades as president. Awad Ahmed Ibn Auf, the defence minister who announced Bashir’s arrest and declared the country would be run by a military council for two years, lasted all of 24 hours.

Salah Gosh, whom I revealed had talked to Yossi Cohen, the head of Mossad, at the Munich Security Conference in February, after being lined up by the Saudis, Emiratis and Egyptians as the future ruler, went soon after.

A lesson learnt

The uprising is delicately poised. Unlike the 25 January revolution in Egypt in 2011, Al Jazeera is not in the front line. Access to the internet has been restricted for months, and newspapers have been censored.

The international media is absent.

The only record of mass demonstrations, which remained on the streets for nearly four months, has been taken by the mobile phones of activists. Women have taken a leading role in the protests.

A sit-in outside the defence ministry in Khartoum is set to continue until a civilian transitional council is formed. Few trust the new faces on the military that continues in power.

The Sudanese protesters appeared to have learned the lessons from Egypt’s failure in 2011

Thus far, the Sudanese protesters appeared to have learned the lessons from Egypt’s failure in 2011. They have stopped chanting that "the people and the army are one", because often they are not.

They don’t trust senior figures in the army or anyone in the old regime to deliver a new one, and nor should they. They are not looking to the outside world for support, because they realise they are on their own.

Why are Sudanese protesting against their government?

+ Show - HideSudanese protests have evolved in the space of less than six months from complaints about bread prices to calls for long-term leader Omar al-Bashir to go and demands for a civilian-led transition to democracy.

Here's a summary of the key moments so far since the protests began.

19 December 2018: People take to the streets in the city of Atbara to protest against a government decision to triple the price of bread, torching a local ruling party office. By the next day protesters on the streets of Khartoum and other cities calling for "freedom, peace, justice". Police try to disperse the crowds, resulting in at least eight deaths. Dozens more will be killed in the weeks of protest that follow

22 February 2019: Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir declares a nationwide state of emergency. He swears in a new prime minister two days later, as riot police confront hundreds of protesters calling for him to resign

6 April: Thousands gather outside the army's headquarters in Khartoum, chanting "one army, one people" in a plea for the military's support. They defy attempts by state security forces to dislodge them and troops intervene to protect them

11 April: Military authorities announce they have removed Bashir and that a transitional military council will govern for two years. Despite celebrations at Bashir's demise, protest leaders denounce the move as a "coup" and the protesters remain camped outside army headquarters.

14 April: Protest leaders call on the military council to transfer power to a civilian government

20 April: Sudan's military rulers hold a first round of talks with protest leaders

27 April: The two sides agree to establish a joint civilian-military ruling council, but talks stall over differences in the composition of the council, with both sides demanding a a majority

15 May: With negotiators reported to be close to agreeing a three-year transition to civilian rule, military leaders suspend talks and insist protesters remove barricades outside the army's headquarters. Talks resume on 19 May but break down again on 20 May, with the opposition insistent that a civilian must head the transitional governing body

28 May: Thousands of workers begin a two-day strike to pressure the military rulers and call for civilian government

3 June: At least 35 people killed and hundreds injured, according to opposition-aligned doctors, as security forces firing live ammunition move to disperse the protest camp outside army headquarters

4 June: General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of the military council, announces that all previous agreements with protest leaders are scrapped and says elections will be held in nine months

A similar dogged determination not to be blown off course is also apparent in Algeria.

Hundreds of thousands of protesters continue to demand the prosecution of "le Pouvoir" (the power) and do not trust Abdelkader Bensalah, the head of the upper house and interim president, to deliver it to them.

Bensalah is in power until elections scheduled for 4 July. The army leader General Ahmed Gaid Salah has turned overnight from a loyal supporter to Bouteflika of 15 years to a man who claims he will guarantee "transparency and integrity" in the forthcoming election.

The arrest of 180 people on Friday after clashes with "infiltrators" says otherwise.

Still, protesters in both Sudan and Algeria appear to have learned important lessons from the first wave of the Arab Spring in 2011.

Arab Spring redux

The first is that the Arab Spring did not "die" either in Egypt, when over a thousand were massacred on one day in Cairo in Rabaa Square in August 2013, or in the civil war in Syria, which began, it must be remembered, with unarmed protesters in Daraa.

The embers of popular revolt stayed alight, despite all the Gulf money poured into repressing it

The embers of popular revolt stayed alight - despite all the Gulf money poured into repressing it, labelling the protesters as terrorists; despite the mass arrests, the deaths in prison, the torture and suffering.

Why? Because the causes of that revolt for a youthful population have, if anything, intensified - unemployment, corruption and repression.

The second is that protesters are paying no heed to those who tell them that they are not ready for democracy and that if they don’t accept the crumbs they are given, their country’s fate would resemble Syria’s, Yemen’s or Libya’s.

They continue to cry for political freedom in the same way that their brothers and sisters did in Tahrir Square. They are young, they are fearless and they will not be fobbed off with fake messages of support.

The third is that popular uprising is just as infectious and transnational as it was eight years ago. If tiny Tunisia could provide the spark for a much greater revolt in Egypt, what could events in Sudan and Algeria lead to?

Same old, same old

No such lessons appeared to have been learned by the counter-revolutionary dictators installed on or after 2013.

The legislative committee of the Egyptian parliament, dominated by supporters of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, will vote on Tuesday to extend the dictator’s current term by two more years, and to allow him to run for one more six-year term.

Almost every Egyptian political faction, from Islamist to secular, realise that Egypt can not continue as it is

A new constitution could be drafted allowing Sisi to extend his term beyond 2030.

The prospect of Sisi carrying on in power for the next two decades appals most Egyptians. If popular opinion could be expressed in Egypt without fear of arrest, disappearance or murder, they would be overwhelmingly against it.

An online petition called Batel or "void" in Arabic has attracted over 250,000 votes despite a gargantuan effort by Egyptian and Sudanese service providers to block the website.

Netblocks, a civil society group mapping web freedom, discovered that internet providers in Egypt blocked access to an estimated 34,000 internet domains to stamp out the opposition campaign against the constitutional amendments.

The collateral damage of this attempt to block an alternative political voice was enormous. "Websites and subdomains unreachable via Telecom Egypt, Raya, Vodafone and Orange include prominent technology startups, self-help websites, celebrity homepages, dozens of open source technology projects, as well as Bahai, Jewish and Islamic faith group websites and NGOs," Netblock reported.

Sisi’s regime is behaving like a frightened little rabbit.

The creators of the website range from two former ministers in Mohamed Morsi’s government to the two Egyptian actors who cheered his overthrow as president in 2013.

Almost every Egyptian political faction, from Islamist to secular, is represented in between. All realise, from very different political backgrounds, that Egypt cannot continue as it is.

Absolute power

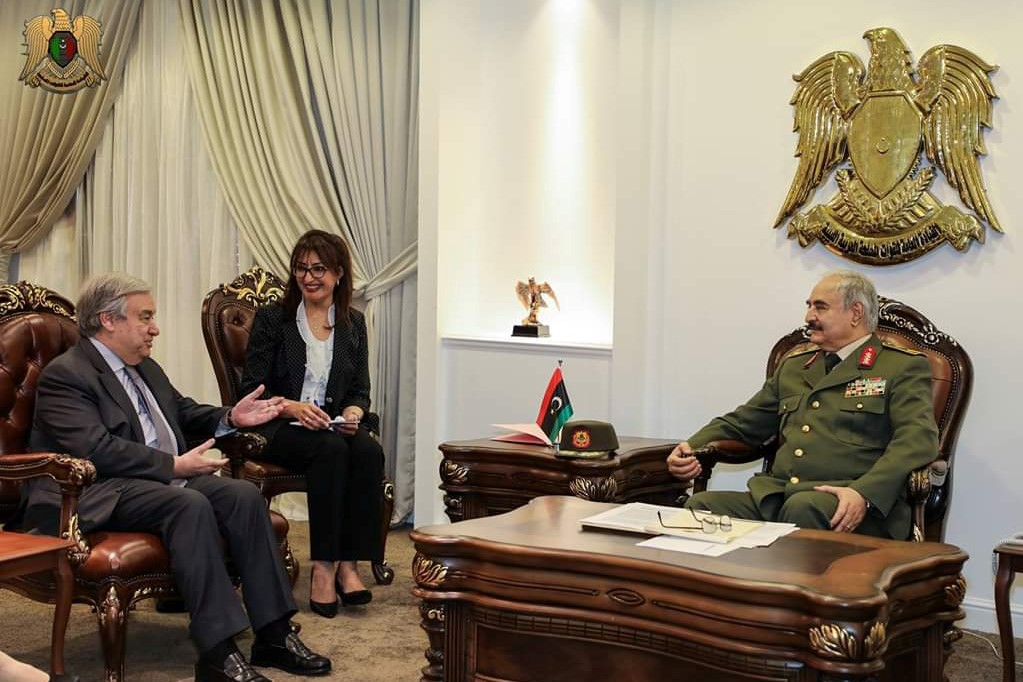

Meanwhile Sisi’s alter ego in Libya, General Khalifa Haftar, is continuing his military offensive on Tripoli which has so far killed 121 and wounded 561 in his bid for absolute power.

A picture of the self-appointed field marshal meeting the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres on 5 April, just before the offensive began, said it all.

The more important man of the two was placed in a side chair, somewhat lower than the one Haftar himself was sitting in. On the wall behind Haftar hung a huge gold crest. This is how Haftar delusionally sees himself governing Libya. He owns it. He runs it. It’s his.

The only green light that mattered to him - before he broke the talks with Fayez al-Sarraj, the head of the Libyan Presidential Council, and launched his unprovoked attack on Tripoli - was the one he got from the Saudis.

This is the breed of military dictator that Libyans rebelled against when they got rid of Muammar Gaddafi.

As Jamal Mahmoud, one resident of Tripoli’s Airport Road area, told MEE: "Libya will not become the next Egypt … We’ve already lost so much. So many of our youth gave their lives to get rid of a tyrannical leader, and their lives were not lost just for another dictator to take Gaddafi's place."

The international community - if such a phrase has any meaning - is split about Haftar. French special forces helped him clear Benghazi of a variety of Islamist groups.

The French oil giant Total is waiting eagerly in the wings for Haftar to secure Tripoli. Italy is backing Tripoli - for now.

If he succeeds, Haftar can only provide one thing - a return to the days Libyans, from all coastal cities, did everything in their power to overthrow.

Seeing is believing

None of this means that the outcomes in Sudan and Algeria are foregone conclusions. A second wave of the Arab Spring has to be seen to be believed. Many obstacles lie in its path.

The Sudanese street has to realise that no party, faction or current, secular or Islamist, can be excluded from the transition process. Whether this lesson has been learned by the Freedom and Change Coalition in Sudan, who are currently calling for a transitional civilian government, which would rule without elections for four years, is open to doubt.

One of the leaders of the opposition parties and the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) trade union is a 77-year-old communist, Mohammad Mokhtar Alkhatib. The other is Ali Alsanhouri, who is leader of the Baath Party, still loyal to Saddam Hussein. Each have a fair amount of history and baggage of their own.

Dictators have no ideology, other than their own self preservation. Saddam Hussein and Bashar al-Assad were Baathist. Bashir was an Islamist and created many splits in the movement.

Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, describes himself as the bearer of something called "moderate Islam". Sisi has proved to be the cruellest of Egypt’s leaders, outclassing Hosni Mubarak’s autocracy, in the name of "stability".

These labels are meaningless if the result is brutal autocracy. It is only reconciliation and inclusion of all currents in the new political process that will ensure it is not hijacked by the ever watchful generals.

All eyes on Egypt

If it succeeds, the new wave of the Arab Spring will only do so in Egypt. For all of Sudan’s and Algeria’s size and importance, Egypt is the litmus test of revolution in the Middle East.

With an economy that is being run into the ground, a middle class that is shrinking, and 30 per cent of the population living below the poverty line, Egypt is being crushed under the weight of its own mismanagement.

One third of the budget is committed to paying the interest of this debt. Dictators can kill, but they appear incapable of ruling. The modern Arab states - those that are not torn apart by civil war - are in a perpetual state of crisis precisely because their rulers can not contain the forces their misrule has unleashed.

By every parameter Egypt today is more vulnerable to popular unrest than it was in 2011. It was in Egypt that the first wave of the Arab Spring was crushed. So too will it be in Egypt that the dictatorship which followed will die also.

Once that happens the writing will be on the wall for everyone else in the Arab world that seeks to deny its population basic human rights.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].