Has the US-Iran conflict reached a point of no return?

On Sunday, Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, appointed General Hossein Salami as the new commander-in-chief for the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC). Salami, 59, was IRGC’s deputy commander for almost a decade.

The shake-up can be viewed as a response to the US designation of the IRGC as a terror organisation.

A different fabric

It is true that the IRGC's former commander, Mohammad Ali Jafari, was also a hawkish figure, but Salami is of a different fabric: an eccentric warmonger who does not miss any opportunity to elevate antagonism with the US to new heights.

And Khamenei knows this all too well.

In a speech earlier this month, Khamenei put a lot of effort into further intensifying Iran-US enmity, strengthening the position of US President Donald Trump and other hawks towards Iran - while likely also making the Europeans think that, perhaps, Trump’s policies on Iran are ultimately the only way to deal with the Iranian system.

Khamenei said: "You, the Iranian nation, if you continue the way you have done so far, you will defeat our enemies. It means you will defeat America."

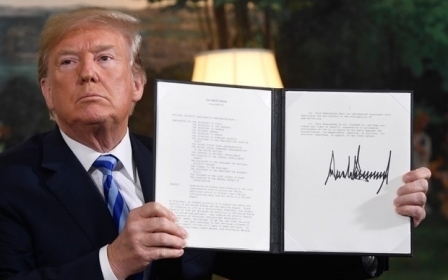

The nuclear deal

Are these remarks just hollow rhetoric for domestic consumption, aimed at reinforcing Khamenei’s own stature among his ultra-conservative followers? That could be one explanation, but the issue is deeper than that.

The culmination of the 2015 nuclear accord with six world powers, which was overwhelmingly the outcome of compromise and cooperation between Iran and the US, emerged as a historic moment, providing an opportunity to break the deadlock of a "no-talks, no-detente" relationship.

But Khamenei immediately followed it up by banning any further negotiations with the US, saying these could “open gates to their economic, cultural, political and security influence” - a move revealing that many, including Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and former US President Barack Obama, had mistakenly indulged in the illusion of moving towards a more peaceful bilateral relationship.

Friends and foes of the Iranian government would admit that Tehran projects its power and influence in the region more than any of its neighbours

And Khamenei is right. In an Americanised Iran - which, considering Iran’s social structure, would most likely occur under a situation of improved relations with the US - the influence of the clergy would erode, as would the system of velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurisprudence) that rules the country.

In a liberalised system, the authority of the Guardian Jurist - as defined by Khamenei, “all Muslims have to obey the order of the Guardian Jurist and submit to his commands” - would be impossible to sustain.

Even the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who held anti-American sentiments, did not think that Iran’s enmity with the US would last forever.

Mohsen Rafighdoost, a founding member of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), gave an interview in 2015 pointing out that Khomeini dissuaded him from setting up the IRGC headquarters in the former US embassy in Tehran. "Why do you want to go there?” Rafighdoost recounts Khomeini asking him. “Are our disputes with the US supposed to last 1,000 years? Do not go there."

Gaining confidence

Khamenei began his rule with anti-Americanism at the heart of his policies. In 1989, when he was elected as Iran’s second supreme leader shortly after the death of Khomeini, he said: “I did not expect, even for a second in my life, what happened in the process of being elected as new leader … I always considered my level [of qualifications] too low to accept not only this highly significant and crucial post, but also much lower posts like the presidency, and other posts which I held during the revolution.”

He clearly lacked the confidence to risk his post and abandon Khomeini’s radical characterisation of the US as the “Great Satan”.

Over time, however, his personality morphed to an over-confident one, due to the emergence of Iran as a regional power.

Looking at the geopolitics of the region, friends and foes of the Iranian government would admit that Tehran projects its power and influence in the region more than any of its neighbours - and probably more than any other country in the world.

How has that happened? Two significant factors in the first decade of this century contributed to the emergence of Iran as a regional power: the US-led invasion of Iraq and subsequent removal of Saddam Hussein, Iran’s sworn enemy; and the skyrocketing of oil prices.

Billions of dollars in extra cash bought Iranians vast influence in the region and led to the expansion of the Quds Force, a special unit of the IRGC responsible for extraterritorial operations.

Micalculations in Iraq

The US miscalculated the outcome of its attack on Iraq, failing to take into account that both countries were Shia-dominated and had been in constant cultural exchange for centuries. The top Shia Iraqi leader, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, still carries an Iranian passport.

The US also failed to see the political influence that Iran had gained during Saddam’s era in Iraq by organising, training and equipping opposition groups that would play an influential role in the post-Saddam era.

In any event, after spectacular regional successes in recent years, with Iran arguably emerging as the biggest winner in the Syrian war, Khamenei has transformed into an ultra-confident commander-in-chief who is not afraid to push conflict with the US even further.

Khamenei views the Iranian system as “the continuation of the first revelation of the Prophet Muhammad”, as he remarked in his 3 April speech.

Some may argue that the fact that Iran has not abandoned the nuclear agreement after Trump’s withdrawal is an indication that Khamenei, despite his anti-US stance in words, is in practice keeping a pragmatic eye on the country’s interests and its abysmal economic conditions.

Khamenei rightly believes that the mechanism the Europeans have created to bypass US sanctions is “more like a joke”. Europe's special purpose vehicle, called INSTEX, was announced by Britain, France and Germany in late January and is supposed to enable trade with Iran and payments in euros for transactions, while avoiding the US sanctions regime.

Iran has set up a parallel trade body but Khamenei maintains that “once again, the Europeans have stabbed us [Iran] in the back”.

The path forward

So, why is he remaining in the deal? He is hopeful that, if Iran resists US pressure for two more years, there could be two positive outcomes. Firstly, a Democrat may take office after the 2020 election and sanctions could be lifted again.

Secondly, under the economic pressure, Iran’s moderates and reformists may crumble and - for the first time since he assumed power in 1989 - a conservative president in line with his world view could be elected in early 2021.

Will the Iranian government, under duress, be forced to provoke a diversionary war to distract the population from their own domestic strife?

The stage is already set. Clearly referring to Rouhani and his foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, Khamenei said last August: “On the issue of the [nuclear] negotiations, I made a mistake … I, due to the insistence of the gentlemen, allowed them to experience [negotiating with the Americans]” but they “crossed the red lines”.

Three major questions, however, arise: First, will Iran maintain stability amid rampant inflation, skyrocketing unemployment and economic hardships?

Second, could a military conflict happen between Iran and the US due to a miscalculation by either side?

Third, will the Iranian government, under duress, be forced to provoke a diversionary war to distract the population from their own domestic strife?

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].