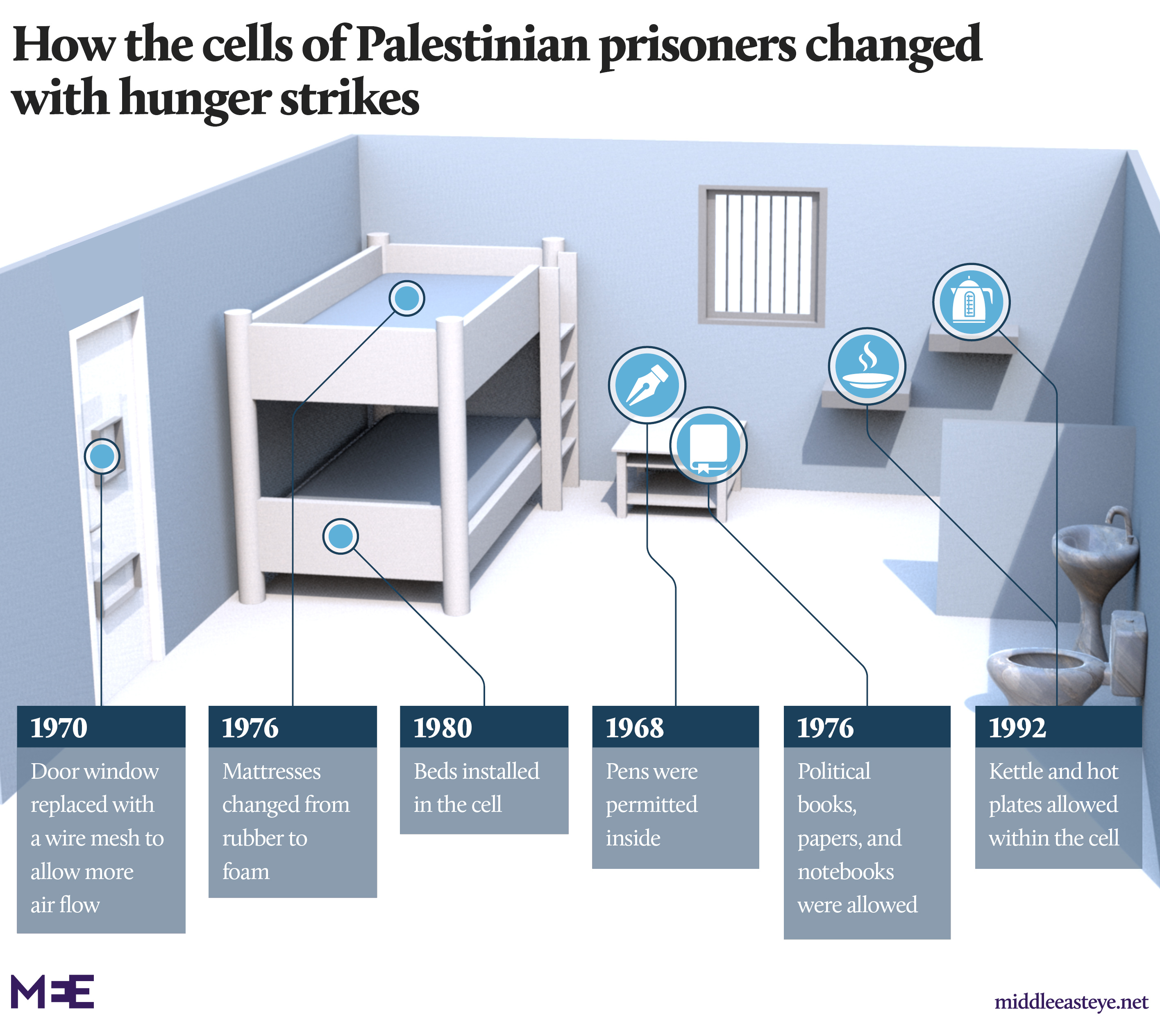

Beds, kettles and books: How hunger strikes changed the cells of Palestinian prisoners

Before 1992, Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli prisons were not allowed to have a kettle or a hot plate in their cell to boil water for tea and coffee.

Thousands joined a 15-day hunger strike that year to achieve this demand, deploying a tactic that had been regularly used by prisoners since 1967 to win concessions and better detention conditions from prison authorities.

Behind every item in the prisoners' cells, and every right obtained, lies the story of a hunger strike.

This applies to the clothes they wear, the books they read, the stationery they write on, the family photos they cherish, and the beds and foam mattresses on which they sleep.

The latest Palestinian hunger strike lasted for eight days and ended on 15 April 2019, after the Israeli Prison Service (IPS) agreed to install landline phones inside prisons and release inmates held in solitary confinement.

There have been at least 25 Palestinian hunger strikes since the 1967 Middle East war when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Imprisonment has been an occupational hazard for Palestinians ever since, with the Institute of Palestine Studies estimating in 2014 that about 80 percent of the adult male population in the West Bank and Gaza Strip had been subjected to some form of Israeli detention since 1967.

Human rights groups say that Israel's holding of Palestinian prisoners arrested in the occupied territories in prisons inside Israel breaches international law.

In February there were about 5,700 Palestinian prisoners languishing in Israeli jails, including 48 women and 230 children, according to figures published by Addameer, a prisoners' rights group. Almost 500 Palestinian prisoners are also currently being held in "administrative detention" without charge.

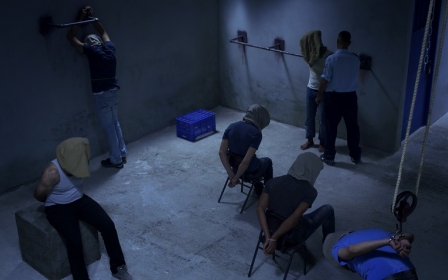

Prisoners on hunger strike see their bodies as their only tool in their struggle against the prison authorities. Prisoners typically refuse to eat any food, drinking only a small amount of salted water each day to protect their stomach and internal organs.

It is a tactic that is fraught with risk and has led to the deaths of prisoners on a number of occasions, such as in 1980 at Nafha prison. Prison authorities frequently respond with intimidation, raids and forcible feeding.

Some of the details of hunger strikes below are based on interviews with former Palestinian political prisoners, and it aims to give a broad picture of the demands of the hunger strikes and how the cells and conditions within the prison walls have changed over time as a consequence of their actions.

1968: Routine beatings banned

This was the first hunger strike launched by Palestinian prisoners in Nablus prison in the West Bank. Israel had occupied the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in June 1967 and imposed military rule in the cities and town of the areas it controlled.

Nablus prison was built in 1876 by the Ottoman authorities. The hunger strike lasted just for three days. Prisoners demanded that Israeli jailers stop the practice of beating prisoners on their way to use the prison's facilities, such as the kitchen and toilet.

1968: Pens, but no paper

On 28 February 1968, Palestinian prisoners started a hunger strike that lasted for eight days in Ramleh prison, southeast of Tel Aviv, and Kfar Yona prison, northeast of Tel Aviv.

Prisoners had several demands, not all of which were achieved. They insisted on their right to refuse to call their Israeli prison guards "Adonai", or "mister" in Hebrew, and eventually this practice was abolished in the two prisons.

Ramleh and Kfar Yona also allowed prisoners to have pens, which they had previously had to smuggle inside. It would take almost eight years more before prisoners were allowed writing paper.

The only paper Palestinian prisoners had in Israeli jails at the time was butter sheets. Prisoners would wash and dry the butter sheet, write a letter on it using a pen or a small sharp stone, and then smuggle the letter outside the prison, after folding it neatly in the shape of a capsule to be swallowed by a visitor or a prisoner who was set to be released.

1970: Sanitary products for women

On 28 April 1970, Palestinian women incarcerated inside Neve Tirtza, an Israeli women's prison southeast of Tel Aviv, went on hunger strike for nine days.

Their demands were similar to their male peers: an end to the routine beating of female prisoners while using the prison's facilities and an end to the use of solitary confinement, among others.

They also achieved an extension to the amount of time they were permitted outdoors, called "Fora" in Arabic, and were allowed sanitary products which were brought in by the Red Cross. They also managed to have the metal shutter on their doors of their cells replaced with a mesh window, improving the air quality.

1976: Mattresses and Maoism

This 45-day strike was the longest since the beginning of the 1967 occupation.

It happened inside Ashkelon prison, located in the town of the same name south of Tel Aviv. The strike was intense, painful, and exhausting physically and psychologically for those who took part.

But by extending the period of their hunger strike from a few days to more than six weeks, the prisoners were able to achieve many long-sought improvements in their detention conditions.

For the first time they were allowed proper stationery, including papers and notebooks, as well as political books ranging from Palestinian nationalist to Maoist texts, and they took charge of the prison library. They were allowed to write to relatives in coordination with the Red Cross, which delivered the letters to their recipients.

Prior to the strike, prisoners in Ashkelon were sleeping on a thin rubber mattress known as a "gomi" in Hebrew, under a light cover. Prisoners slept on the gomi on the floor, but during the day they had to put the mattress away and sit on the floor. Anyone who sat on the gomi was punished.

As a consequence of the 1976 strike, prisoners were given foam mattresses. They also demanded an increase in the quality and quantity of the food, which was cooked by Israeli prisoners sentenced for crimes.

The breakfast menu consisted of one pitta bread for every eight prisoners, one tomato for every four, and olives for each prisoner. For lunch, one rice plate for every two prisoners, a bowl of soup and piece of meat or a small fish.

Each prisoner had two plates and one cup.

1980: Beds allowed for the first time

Three Palestinian prisoners died during the hunger strike in Nafha prison that started on 14 July 1980 and lasted for 33 days.

Rasem Halaweh, Ishak Maragheh and Ali Al-Jaafri died while being forcibly fed by Israeli prison guards who used a sharp-edged tube which was inserted through the nose and pushed down into their stomach.

Nafha prison was built in May 1980 in the Negev desert to isolate Palestinian political leaders and confine them in one place, to weaken the morale of prisoners. When it opened, Nafha had a capacity of 100 prisoners.

Conditions in the desert prison were terrible. Sand and soil mixed with the food. Cells were overcrowded and lacked proper ventilation. Prisoners did not have stationery and were allowed outdoors for just one hour a day in the prison yard.

No more than two prisoners could walk together in the yard, and they were required to keep their hands behind their back and were not allowed to look up.

The Israeli prison authorities took some of the hunger strikers to Ramleh prison, where they were forcibly fed and some of them died eventually.

But the hunger strike achieved its demands.

Beds, for the first time were set up in Nafha and gradually in other prisons. Cell sizes were extended. Mesh windows replaced the metal shutters on the cell doors. Family photo albums and stationery were allowed in.

1984: Underwear and televisions

In September 1984, Palestinian prisoners started a hunger strike in al-Junaid prison in Nablus that lasted for 13 days and is considered a turning point in the campaign for better living conditions within the prison walls.

Haim Barlev, Israel's minister of police, visited al-Junaid and met and talked with the prisoners. Barlev crossed red lines set up by his predecessors when he allowed in televisions, radios and civilian clothes, and better food and medication.

Prisoners had previously worn the clothes of former inmates and made themselves underwear from old bed sheets and covers.

Eventually, pyjamas, speakers and tape recorders were allowed in, and the amount of money that prisoners were permitted to spend in the canteen was increased.

1992: Kettles and fizzy drinks

On 25 September 1992, about 7,000 Palestinian prisoners launched a collective hunger strike across all prisons that lasted for 15 days.

The hunger strike was a success, as prisoners managed to force the Israel Prison Administration to shut down the solitary confinement wing in Ramleh prison and to end the routine strip-searching of prisoners. Prisoners were also permitted increased time for family visits, and they were allowed to have hot plates and kettles in their cells.

They were also allowed to buy fizzy drinks from an expanded canteen shopping list.

- Additional reporting from the West Bank by Shatha Hammad

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].