The rise of Libya’s renegade general: How Haftar built his war machine

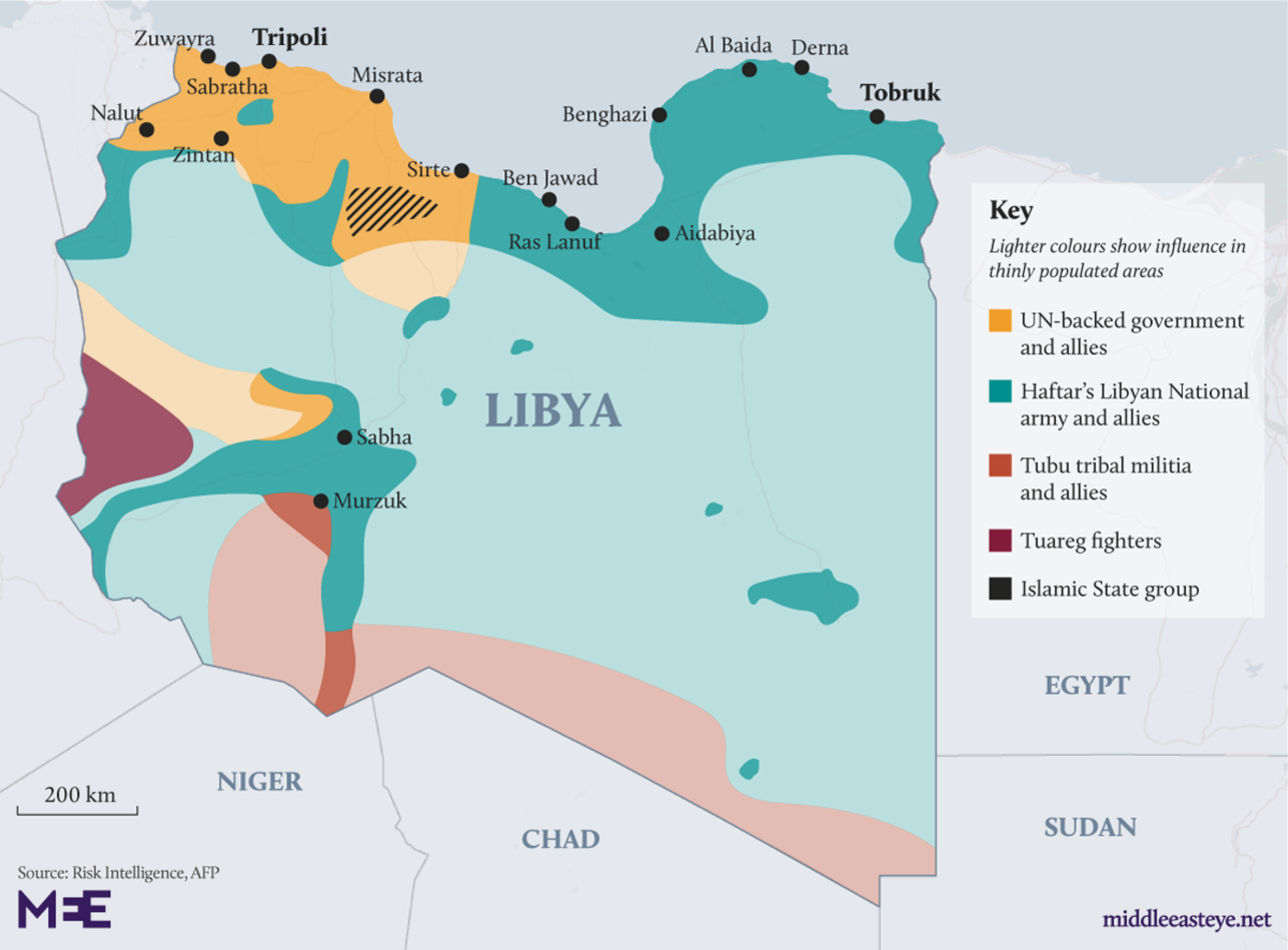

From its powerbase in eastern Libya, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) has gradually extended the territory under its control and the firepower at its disposal, to the point where it now challenges the authority of the country’s United Nations-recognised government in Tripoli.

Since launching “Operation Dignity” against Islamist militant groups around Benghazi in May 2014, Haftar’s forces have benefited from international support that has provided them with weapons and military vehicles in contravention of a UN embargo imposed in February 2011 as protests against then-leader Muammar Gaddafi exploded into full-scale civil war.

UN resolutions on Libya in September 2011 and March 2013, allowing the provision of non-lethal equipment, technical assistance, training and financial support, have further enabled Haftar to maintain and extend an arsenal containing elements – on land, air and sea – of a conventional military force.

Haftar has also received political, diplomatic and military backing from a range of states, including the United Arab Emirates and Egypt (which are reported to have persuaded US President Donald Trump to back Haftar's offensive against the UN-recognised government), Russia and France.

In recent weeks Haftar’s forces have reportedly conducted air strikes and drone strikes in Tripoli and the surrounding areas, and deployed a recently acquired warship to an eastern oil port.

The following is a summary of the forces under Haftar's control and the key events that have contributed to his emergence as a warlord on the southern shores of the Mediterranean.

Militias, pickups and Soviet-built weaponry

The Libyan National Army is actually a group of militias rotating around a regular army nucleus representing a force of about 25,000 men. The regular army has a total of about 7,000 members.

Haftar can also count on some 12,000 auxiliary militia members, including several Sudanese units from Darfur, Chadian militia fighters, and 2,500 members of the allied Zintan brigades, who were considered among the most effective fighters during the war against Gaddafi.

Haftar's forces are also bolstered by fighters from allied tribes in southern Libya such as Awlad Suleiman.

The equipment available to these disparate forces ranges from Toyota Land Cruisers to Russian-built tanks. Some units are very well equipped, with recent material including armoured personnel carriers, some provided by the UAE.

Toyota pickups are considered more important than armoured cars because they can be easily equipped with various 12.7mm and 14.5mm machine gun-type weapons and 106mm recoilless guns.

Most of the equipment dates back to the Gaddafi era, much of it of Soviet and Eastern European vintage, including T-54 and T-55 tanks, BM-21 Grad missile launchers and self-propelled Howitzer guns.

2014: The Free Libyan Air Force splits

Significant quantities of aircraft and helicopters were delivered into Libya by supporters of the country’s various factions during and after the civil war against Gaddafi, despite a UN Security Council embargo covering arms exports, the provision of weapons and ammunition, military vehicles and equipment, and related spare parts.

But a lack of experienced pilots and ground personnel, plus the poor condition of older equipment, much of which had been in storage for nearly two decades, made operations, maintenance and refurbishment a major challenge for the post-Gaddafi Free Libyan Air Force (FLAF).

When a battle for political authority broke out in 2014 between the country’s rival parliaments, the General National Congress (GNC) in Tripoli and the House of Representatives (HoR) in Tobruk, the FLAF also split into two entities.

One, the Libyan National Army/Air Force (LNA/AF), sided with Haftar and pledged allegiance to the HoR in Tobruk. The other, originally known as the Libyan Dawn Air Force (LDAF) sided with the GNC in Tripoli and the allied Misrata militia.

Most of the available pilots, aircraft and equipment were taken over by the LNA/AF, which inherited the majority of the FLAF’s MiG-21 and MiG-23 fighter jets. The LNA/AF also took over five Russian-made attack helicopters, three Mil Mi-35s and two Mi-17s, which had been donated by Sudan in 2013.

In the west of the country, the LDAF was left in control of the Misrata and Mitiga air bases, and random ageing aircraft, many dating from the Cold War era and built in Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.

Egypt and the UAE back the LNA/AF

In 2014, Egypt began providing support to the LNA/AF through donations of combat aircraft and helicopters withdrawn from service in its own air force. As a consequence, seven MiG-21s jets and eight helicopters, together with significant consignments of spares and ammunition, found their way to Tobruk.

In April 2015, the UAE purchased four helicopters from Belarus, and delivered them to the LNA/AF.

In June of the same year, a United Arab Emirates Air Force IOMAX AT-802 light striker was sighted at an unidentified Libyan air base, albeit with its national markings hidden. The aircraft, commonly known as the Air Tractor, is a variant of a plane commonly used as a cropduster that is instead fitted with rockets and bombs.

Meanwhile, the LNA/AF acquired additional aircraft through the capture of the el-Woutiya air base, in western Libya, in August 2014, where a number of Mirage fighter jets and Sukhoi Su-22s fighter-bombers were stored inside hardened aircraft shelters.

In late 2015, its ground crews started overhauling these planes, with one of the Mirages operational by the end of the year. In early 2016, the LNA/AF suffered the loss of three MiG-23s and one of their pilots, and began overhauling three more MiGs found at al-Abrak air base.

In February, an Su-22 made its initial flight, followed by two more MiG-23s in May. One of them crashed just two months later.

Such overhauls are time-consuming, technically demanding and require experienced personnel, money and spare parts in abundance that might have been expected to stretch the limited resources of the LNA/AF.

But operational MiG-21s and MiG-23s have continued to fly combat missions, and new pilots have also been trained in Egypt, with 35 graduating from training there in July 2016. A new Su-22 was added to the LNA/AF’s fleet in November that year.

UAE pilots fly sorties for Haftar

In 2015, the UAE donated two S-100 Camcopter surveillance drones to the LNA/AF. One of them was spotted flying over Benghazi in May 2016, suggesting that either Libyan operators had been trained to control the drones or Emirati operators were on the ground at the LNA’s main Benina air base.

In June 2016, photos circulated apparently depicting what Haftar's opponents in Benghazi, the Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries (SCBR), said were US-made bombs dropped by Emirati aircraft on the city.

In fact, the bomb in the photos was a Turkish-made, US-designed Mk 82 with a laser-guidance kit, a weapon which can be carried by the Air Tractor.

In September 2016, SCBR media published more information about the types of aircraft the group said were involved in air strikes in Benghazi. According to the figures, Air Tractors had flown 27 bombing missions, while reconnaissance drones had flown 235 flights.

Emirati pilots flying sorties for Haftar: How MEE broke the story

+ Show - HideIn 2016, Middle East Eye obtained leaked air traffic control recordings which suggested that the United Arab Emirates and western powers were providing Haftar with support beyond weapons and money.

The recordings, obtained from the Benina airbase, Haftar’s military headquarters, indicated that Emirati fighter pilots were taking part in operations against militia fighters in eastern Libya.

In the tapes, pilots and air traffic controllers can be heard discussing the coordinates for attacks. Some of the recordings are in Arabic but at times air traffic controllers and pilots can also be heard speaking in American-, British-, French- and Italian-accented English.

In one audio file, a pilot with an Emirati accent is heard relaying coordinates to a Libyan officer in the operations room. He is then told to “check for movement” because they "don't want to waste any bombs”.

Read the full story here.

On 2 November 2016, an S-100 Camcopter drone performed a reconnaissance mission over the residential district of Ganfouda two hours before an unmanned armed drone carried out an an air strike in the area.

Ten days later, an Air Tractor belonging to the Emirati air force struck the same area, killing at least four civilians including two children, and injuring another child. Drones launched four other air strikes in Ganfouda later the same day.

This was not the first time the SCBR had claimed that Emirati aircraft were involved in bombing missions in Benghazi. Satellite imagery from July 2016 confirms that the Emirates has deployed six Air Tractors and three armed drones, probably Chinese-made Wing Loongs, to Al Khadim airport in Marj province.

Russian spare parts and Iranian drones

Since visiting the Russian aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov in the Mediterranean in January 2017 to meet Sergei Shoigu, the Russian defence minister, and General Valery Gerasimov, the army chief, Haftar has also benefited from Russian technical support.

Within weeks of the meeting, deliveries of spare parts from former Russian MiG-23s began arriving at al-Abraq airbase.

In April 2017, the LNA/AF lost two fighter-bombers and an experienced pilot, increasing its losses to eight aircraft - three MiG-21s and five MiG-23s - as well as six helicopters, including two Mi-24/35 gunships in accidents or combat losses since January 2016.

The refurbishment of aircraft stored for decades in hangars or outdoors, using spare parts from Russia and Egypt, was by now no longer sufficient to maintain the fleet.

During the period that the LNA/AF lost 14 aircraft, it renovated just six MiG-23s. Training pilots to fly the MiG-23 also proved challenging because training courses were no longer available for the Soviet-era fighter, and the LNA/AF had to write its own syllabus. In July 2017, the LNA/AF lost another MiG-23 over Derna.

In October 2017, it was confirmed that the Libyan National Army had obtained Iranian-made Mohajer-2 drones. Given that the LNA’s strongest backers are Egypt and the UAE, who are both allies of Saudi Arabia and hostile to Iran, the most likely supplier of these appeared to be Sudan.

While Khartoum under now-deposed Omar al-Bashir had generally supported Tripoli-aligned militants in Misrata and the GNA, there are indications it also occasionally aided the LNA.

In May 2018, at Brak al-Shati airbase, an LNA Air Force L-39, a Czechoslovakian-built jet trainer, made its first flight after more than 31 years in storage. In November, engine tests were conducted on a restored MiG-23 at al-Abraq airbase.

As the offensive against Tripoli began, the LNA/AF therefore had about 15 operational aircraft: about eight MiG-21s (one was shot down over Tripoli by a Chinese-made air defence system), three MiG-23s, two Su-22s and two Mirage F1s. It also maintains the single L-39 jet for training.

Haftar's navy: French inflatables and an Irish-built flagship

Most of Libya’s Gaddafi-era naval fleet was destroyed by NATO bombing in support of opposition forces during the 2011 civil war.

However, at least one of six Croatian-built fast patrol vessels acquired in the 2000s remains in service.

In December 2012, a series of four Damen Stan Patrol 1605s (named Burdi, Sloug, Besher and Izreg), were delivered to the Libyan government. The 16m-long vessels require a crew of four and typically perform coastal patrol duties. These were followed by four more of the patrol craft in March 2013.

In April 2013, Islamist militia forces in Benghazi shelled and destroyed an LNA boat in Julyana Port south of the main port in central Benghazi.

In May 2013 the Libyan Navy took delivery of 30 rigid-hulled inflatable boats (RHIBs) ordered from the French military boat maker Sillinger. These high-powered boats are used for maritime border patrols and coastguard duties, protecting vital installations as well as monitoring illegal sea-borne intrusions and landings.

The following month, the Libyan Navy received two Raidco Marine RPB 20 patrol boats from France. One, named Janzour, is based in Benghazi while the other, named Akrma, is based at Tobruk Naval Base. They were handed over to the Libyan Navy in France, following which Raidco spent over a month training 32 Libyan officers and sailors and six maintenance staff.

In May 2014, like the former Free Libyan Air Force, the Libyan Navy split between eastern and western Libya since the fleet was mainly located in the regions of Tobruk and Tripoli.

The LNA used its fleet in maritime security operations during the Benghazi blockade in 2015/2016 to prevent any maritime supplies reaching its militant opponents, as well as to prevent the flight of Islamist leaders from Benghazi and Derna by sea.

The LNA Navy’s latest acquisition is the flagship Alkarama (Dignity) offshore patrol vessel. Built in Cork, Ireland, in 1979, the former Irish naval vessel was delivered to Benghazi in May 2018 after being bought at auction. It was registered by a company based in the UAE. Last month, the Alkarama was deployed to the Ras Lanuf oil port in the east of the country.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].