Aladdin to Thief of Baghdad: How film posters created an Orientalist fantasy

In a month that sees the worldwide release of Disney's latest incarnation of Aladdin, an exhibition in Lebanon has opened a window on a century of film poster portrayals of the East through western eyes.

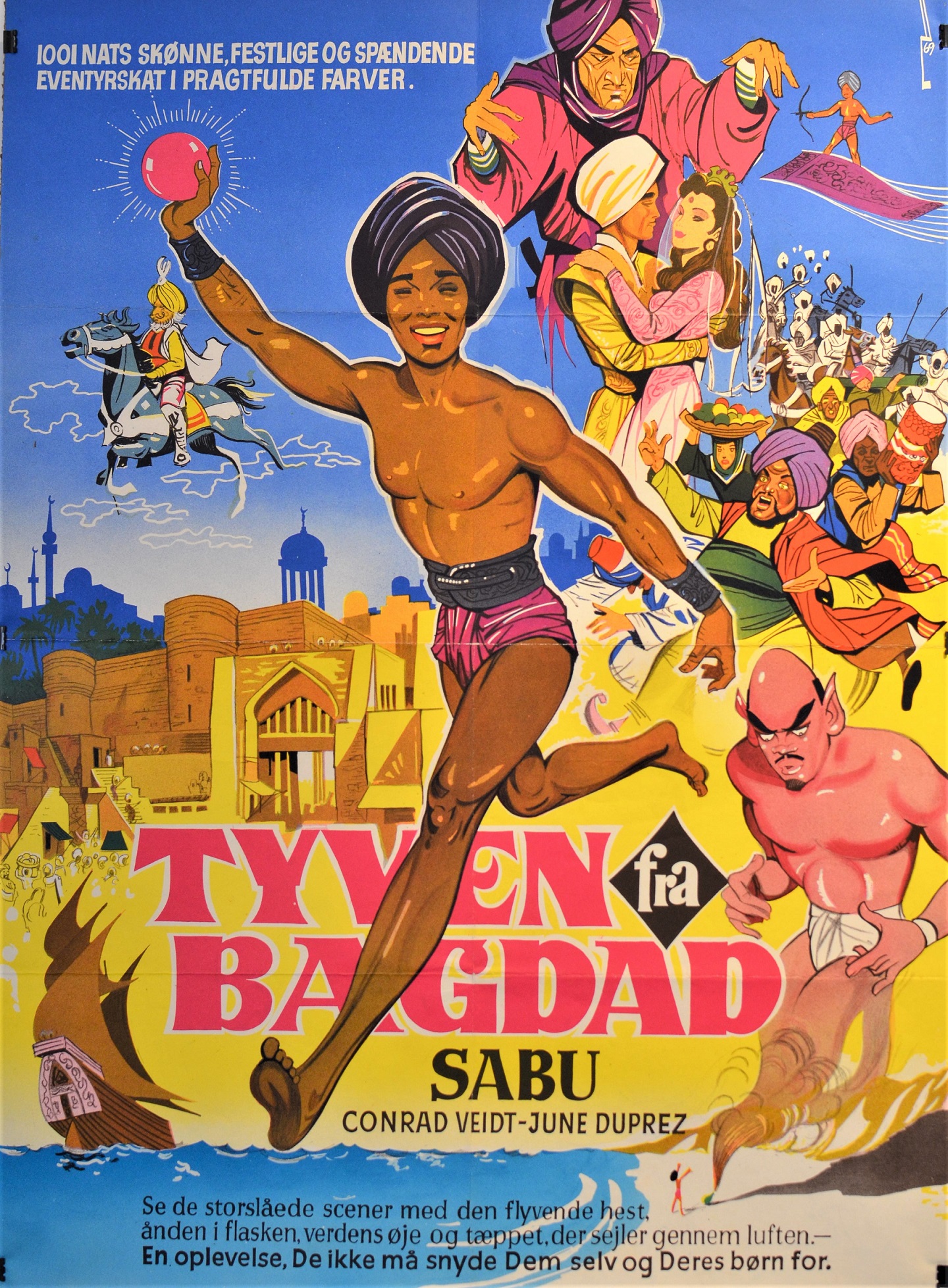

On a wall in Beirut's Dar El-Nimer gallery, a Czech-language poster for the 1978 film Thief of Baghdad takes inspiration from Ottoman miniatures. Before a stylised blue, white and green background, a turbaned man on a horse holds a bird aloft.

Next to this delicate illustration, a much larger, Arabic-language poster for the 1940 version of the film, depicts - in realist strokes and bold colours - a glaring turbaned man towering over an embracing couple on a flying carpet, against a backdrop of green, yellow and pink minarets.

To the right, an English-language poster for the 1924 Thief of Baghdad, the original, adopts an art deco aesthetic and dusky palette: a man brandishing a scimitar swoops towards a white city on a flying horse over the obsidian sea.

Abboudi Abou Jaoude is the owner of the posters and curator of Thief of Baghdad: Arabs in World Cinema, an exhibition comprised of movie posters made between the 1910s and 1990s for films set in the Middle East but made, overwhelmingly, in the West.

This, he says, is what he wants visitors to see: the variations (personal, geographical) in the depictions of these films. “Each [artist’s] personality has its own distinct spirit. So I wanted to show this distinction, and these types in every country.”

Walking through Thief of Baghdad, what is striking about these movie posters is not necessarily the individual genius of the artists, or the intriguing regional or temporal differences among their work, but rather how similar their output is.

Only one Middle East

There is only one Middle East, these posters seem to shout. It is the one with dark-hued baddies and half-naked, white-skinned lust objects, who occasionally appear with bits of their faces covered, even if their bodies are not. It is the Middle East of onion domes (are we in Russia?) and carpets that may or may not fly, and fezzes and horses and sand stretching out of frame.

“When I was collecting them,” Abou Jaoude tells Middle East Eye, “I discovered that they look like the same stereotypes [depicted by] artists in the 18th and 19th centuries. It’s as if, when we see this poster, we’re seeing a painting drawn by those same artists.”

These designs are cheerful, of course; they’re distinctive, visually abundant. The colours are bright and alluring, the scenes intriguing. There are ouds and pouting women - one of whom is wrapped in chains above the title Babes in Baghdad (“The shapes that shook a Harem Empire! … All its spectacle now in EXOTIC COLOR”).

The goal of the artists, the introductory message tells us, was “seducing the public”. Many of them, it seems, were less interested in accurately representing the movie than in exercising their artistic licence.

A poster for the 1952 feature Thief of Damascus - “A group of friends go on a mission to fight the evil sultan” - includes no reference to the group of friends, favouring instead a pile of women in gauzy green outfits on a green carpet, haloed by a stylised minaret outline, behind which the sultan - in devilish red tones, his eyes ablaze - wields a scimitar from a rearing horse.

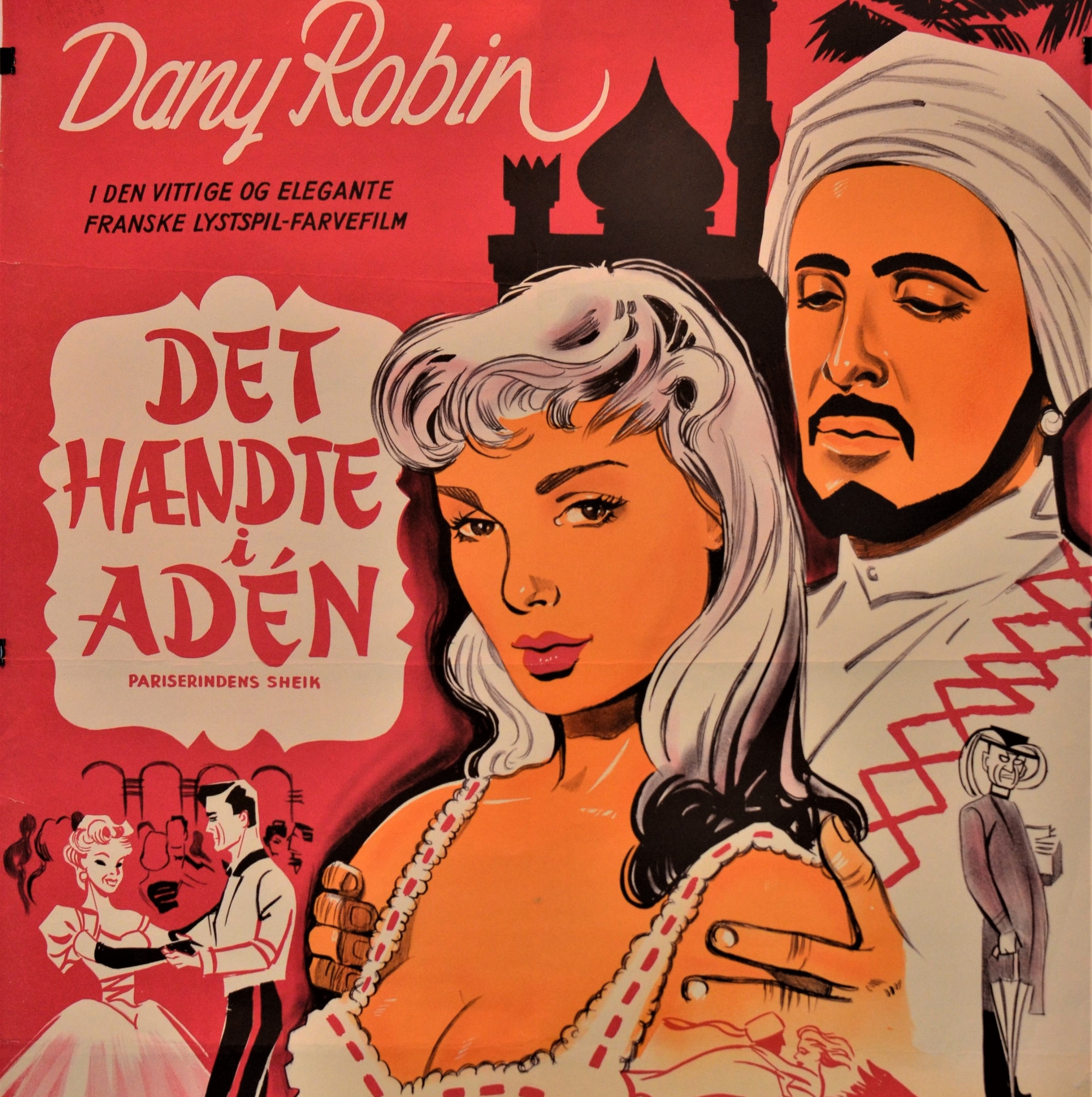

Nearby, a bright pink Danish-language poster for It Happened In Aden (France, 1956) shows a swarthy, covetous, moustachioed man somewhat sinisterly gripping the shoulders of a blonde, busty woman, in front of the silhouettes of an onion dome, a minaret and palm trees. The plot? “Chronicles a group of French comedians stranded in Aden.”

The posters are grouped loosely into genre - love/lust, adventure, fantasy - and by subject matter. There’s a whole section devoted to the Thief of Baghdad films, which borrowed loosely from The One Thousand and One Nights, the classic collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian folktales, the first mention of which can be found in a ninth-century fragment. The rest of the exhibition offers dozens of other posters for movies based on tales from the Nights: Aladdin, Ali Baba, Sinbad.

Repetition is everywhere - of plots, titles, tropes and images. A handful of productions are represented more than once, by posters made for different markets in different languages.

Borrowed archetypes

Many of the films seem to be a corruption or reworking of something else: the fantasy films repurposing the myriad tales of the Nights, or the James Bond knock-offs in the “adventure” sections, or the comedies subverting the tropes of these grandstanding epics.

Indeed, even the much-loved, archetypal character of Aladdin was largely based on the eponymous petty criminal in the Thief of Baghdad films.

Such loose re-workings come from a long tradition. “We’re hard-pressed to pinpoint any one singly original manuscript, so the book history of The One Thousand and One Nights has been rife with iterations and translations,” says Samhita Sunya, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia whose work focuses on the cinema of the Middle East and South Asia.

The opportunities offered by the tales for spectacular visuals, and their longstanding popularity as lavishly illustrated texts, makes their enduring cinematic popularity unsurprising, she says.

“Here’s the issue: One Thousand and One Nights are such magical marvellous stories. I think it’s important to remember that a lot of these tales are occurring in the realm of imagination.”

The tendency of certain characters or themes to be taken literally and used at tools for understanding parts of the world is “ridiculous,” she says. “These are tropes that end up reifying certain deeply racialised hierarchies.”

From ridiculous to sinister

It may be fatuous to point out the problematic stereotypes promulgated by Golden Age Hollywood. It’s more interesting to ask whether things have changed.

Greg Burris, a film and cultural theorist at the American University of Beirut, says: “These are obviously stereotypes, they’re obviously problematic in many ways, but they don’t have the same maliciousness as a lot of Arab stereotypes today in western media.”

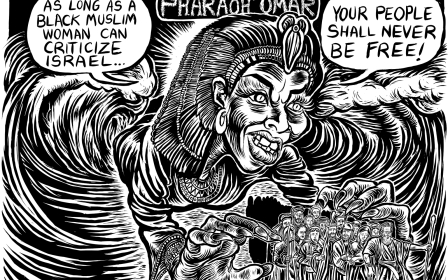

We have now, in the post-9/11 world, reached what Daniel Newman, an Arabic professor at the University of Durham, terms the fourth period of Middle Eastern representation (following distinct periods based on the lascivious Arab, the Nights and the oil-rich Arab), in which, finally, “Arab and Muslim have coalesced into, of course, ‘the terrorist’.”

Some of the hysterical rhetoric of the posters in the “adventure” section might have been creatively ripped from modern headlines: “Come to savage seething Arabia on a terror search… Filmed amidst the mysteries of today’s high-tension Middle East!”

But the baddies, here, are not so sinister, and the action is presumably partly pleasurable because of its remoteness from the lived experience of the audience. In Embassy (1972), a Cold War spy drama set in Beirut, the real bad guys are not the Arabs but the Russians.

Contemporary films paint the Middle East as a harsher, less charming, more nefarious place, its inhabitants alien and terrifying rather than alien and intriguing. “The terrorist [narrative] is so dominant that it crowds out every other aspect,” Newman says.

He suggests that it is only latterly that the filmic (and popular) conflation of “Arab” and “Muslim” has taken force and Orientalism has become bound up with religious rather than ethnological references. But the Thief of Baghdad exhibition makes clear that the flattening of the majority-Muslim world (North Africa and West, South, and Central Asia) into one fantasy realm - one culture, one aesthetic - is nothing new.

“It’s not just the Arab world” represented in these posters, says Burris. “It’s the Arab world/Muslim world/Iranian world/Turkish world. It all comes together.”

Is this Lebanon?

In posters for The Lebanese Mission (France/Italy, 1956), camels roam across deserts, a Bedouin girl dances near a tent, and oil rigs (or are they uranium facilities?) are silhouetted against a red sun.

Lebanon has no deserts, its marginalised Bedouin population are hardly a visible presence, and it is only now beginning to search for offshore oil (any potential uranium traces are the residue of war).

It seems likely that one-note depictions of Islam, Muslims, and the diverse regions in which they make up the majority feed into toxic, violent ideologies as well as casual Islamophobia. “If your only source for Beirut is that movie that came out, what do you have to compare it to?” Burris asks. “Nothing. So that’s the danger in popular culture, and it’s also the danger in the news.”

“I don’t think [the media] creates anything like Islamophobia,” Newman says, “but it can reinforce it.”

The harmful potential of a single story and its few, nuance-less character types (the oppressed woman, the dangerous bearded man, the brainwashed child), is that so little space is left for narratives that buck that trend - complicated narratives in which ethnic or religious identities are not the only things that define non-Western characters.

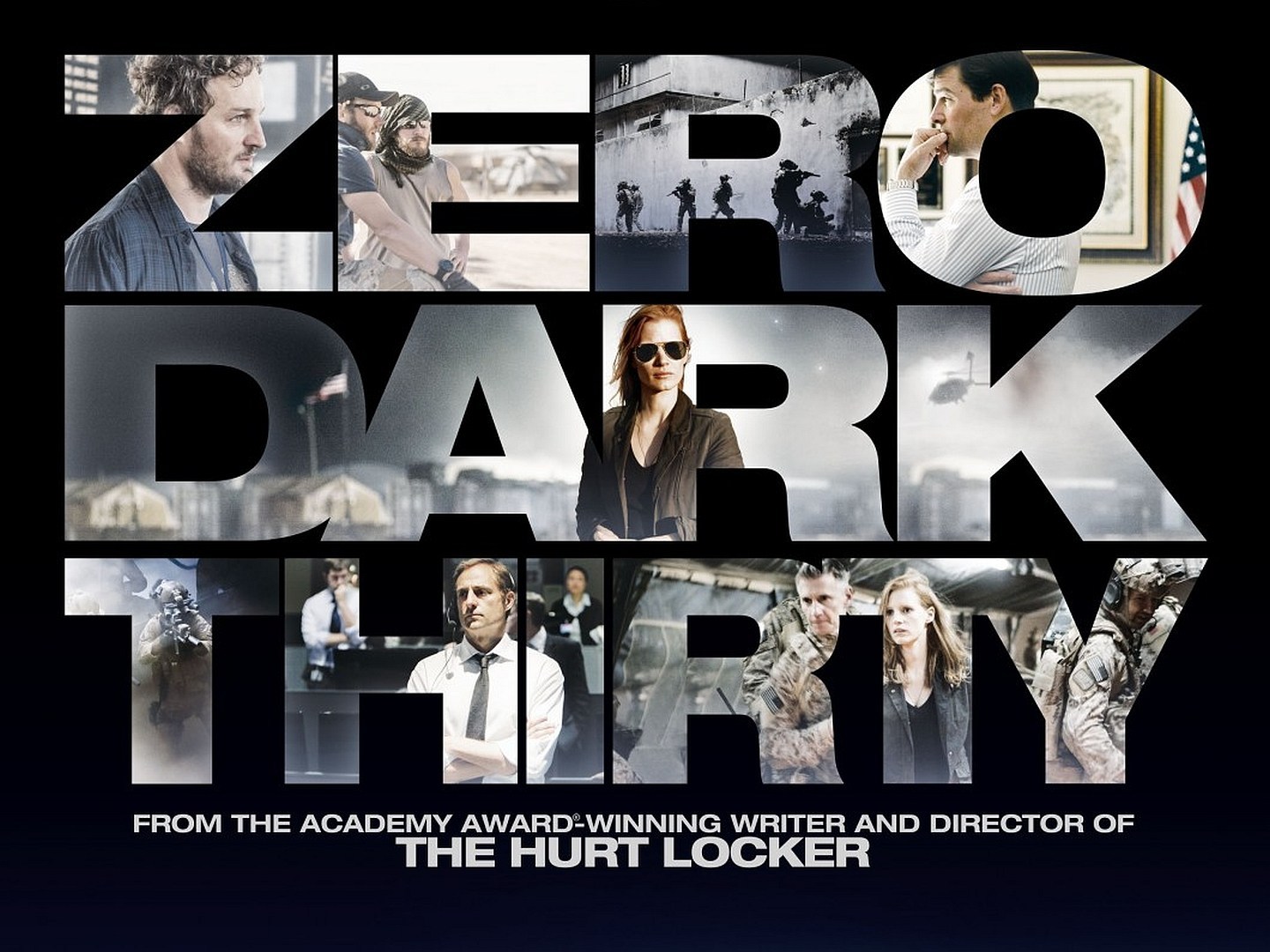

Most contemporary posters for films set in the MENA region seem to ignore these characters entirely. In posters for Beirut, Rules of Engagement, Syriana, Body of Lies, and Zero Dark Thirty, the heads and bodies of Western film stars hover above murky backdrops of machinery, flames, tenements, helicopters.

The specific setting melts away almost entirely as the protagonists, who are invariably alien to those settings, loom large. The Muslim world becomes a minimalist set on which the West can play out its own obsessions.

Nostalgia

The Thief of Baghdad exhibition has little in the way of exegesis, and viewers are left to craft their own reactions to these cheerful Orientalist fantasies. Despite the obvious critiques to be made of the posters and the films they represent, Abou Jaoude suggests that responses are often nostalgic.

“This lady said to me: ‘It’s a return to 70 years [ago]… It’s nostalgia for us, and for the new generation, they love to see it, and to know it.”

The same nostalgia, perhaps, will drive ticket sales to Disney's new, live-action Aladdin, due for release this month, whose promotional materials suggest an aesthetic and an atmosphere at one with its predecessor (which sparked controversy over its racial politics).

At a time when uncomfortable history is being torn down or papered over in many quarters, Abou Jaoude’s enthusiasm for his collection and the cinematic history, historical discourse and inter-cultural relationships it illustrates is both surprising and contagious. “What he’s been doing is an independent effort of one person that the state itself isn’t capable of keeping up with,” says Omar Thawabeh, Dar El-Nimer’s communications manager.

Abou Jaoude’s eyes light up when he speaks of his collection, his gestures grow more expressive. His project is important, he says, “because we have no memory, frankly. There’s nothing documented. So we wanted this to exist.”

"Thief of Baghdad: Arabs in World Cinema," at Dar El-Nimer for Arts and Culture (America Street, Rue Clémenceau, Beirut) continues until 25 May 2019

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].