Cold War and ancient cities: How US spy planes revealed the secret history of the Middle East

As dawn breaks at the US airbase at Incirlik, a black aluminium plane takes off into the skies of southern Turkey.

Crammed into the single-seat cockpit of the Lockheed U2, its pilot will spend nine hours criss-crossing the Middle East, clocking up thousands of miles.

There is also another passenger on board Mission 8648: a Hycon Model B panoramic camera, slung under the plane’s belly. Along with a tracking camera, it will click away throughout the flight, taking more than 6,000 photos and capturing objects as small as three feet from an altitude of 12 miles.

It is 30 October 1959 and the height of the Cold War. During the previous 12 months, Washington and Moscow have clashed over Berlin and the rise to power of Fidel Castro, Cuba’s communist leader. Washington is also spooked by the Soviet space programme, which has taken the first photographs of the far side of the moon.

U2 aircraft are flying numerous missions over the Middle East, primarily taking photographs of military installations and cities. But among the shots are many that will prove invaluable to 21st-century archaeologists and environmentalists: photographs of sights that, more than half-a-century later, have either ceased to exist or else are barely visible.

Ancient urban canal networks. Prehistoric hunting traps. Marsh Arab communities uprooted during the late 20th century. Archaeologists say the sites provide a vital window into how civilisations lived.

“We knew images from those flights existed and that they were stored as part of the US National Archives,” says archaeologist Emily Hammer at the University of Pennsylvania, who is now researching the photos.

“The use of aerial photography goes back a long way, but in terms of quality these images are fairly astounding.”

Cold War over the Middle East

The late 1950s was a time of bitter rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union in the Middle East. Washington was particularly alarmed about Moscow’s growing influence in Egypt and Syria.

The Middle East reconnaissance programme - codenamed CHESS - ran between June 1956 and May 1960. From Turkey it made at least 52 clandestine missions, of which 15 flew over the USSR as it sought intelligence about military activities, including suspected nuclear facilities.

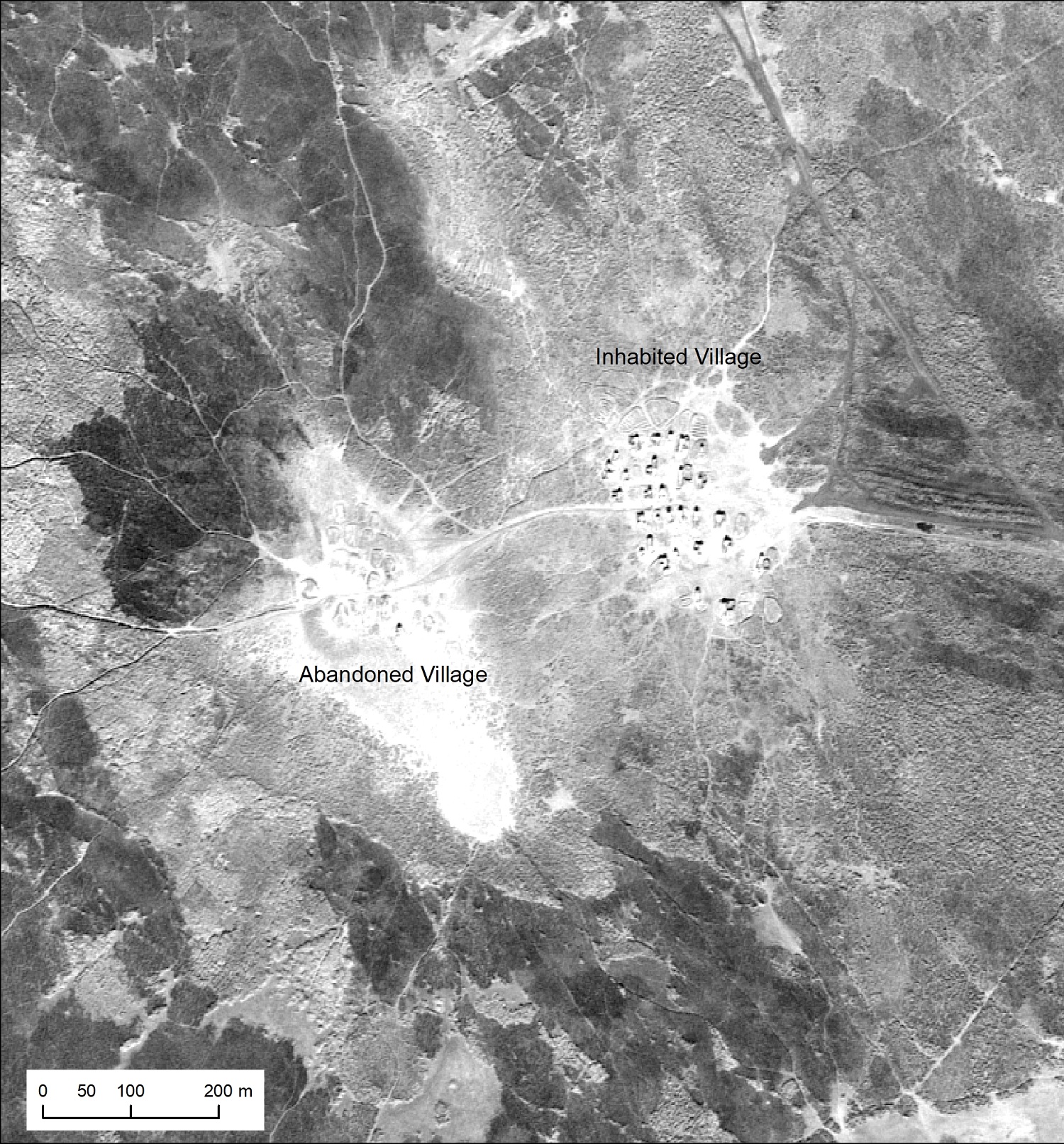

The images that the U2 missions captured record ground sites which do not exist anymore. Conflict, along with intensive agricultural development and urban sprawl, have altered large parts of the region. “The imagery from these missions captures the landscape of Cold War hotspots of the 1950s and 1960s,” write Hammer and Jason Ur at Harvard University, reporting the results of their research in the journal Advances in Archeological Practice.

The missions flew over Egypt, Jordan, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Iran among others. The cameras were only turned off while the planes were in Turkish airspace. Flights over Israel, including the Dimona nuclear plant, gathered material which has yet to be made public.

The missions are also notable for the quality of the photos, most of which were taken with the B Camera, which had a 36-inch lens and resolution of 100 lines per millimetre. Its images were better, for example, than those of the CORONA project, also of the Middle East, which were taken by the KH4B satellite between 1967 and 1972.

The U2 missions took off early in the day, ensuring that the long shadows on the ground would highlight key features of the landscape. Missions during late autumn and winter ensured there was less dust in the atmosphere, improving the clarity of the photography.

Stephen Davis is an archaeologist at University College, Dublin and chair of the international Aerial Archeology Research Group.

“While the U2 missions were concentrating on military installations they did blanket coverage of the area with what were, even by today’s standards, remarkably good cameras," he says, "probably equivalent to the images provided now by Google Earth."

But sorting through and documenting the U2 pictures was a long, laborious task.

“Actually getting hold of them and piecing them together was a lot of work,” says Hammer, whose team spent months wading through thousands of declassified documents, files and negatives to make sense of the programme.

The declassified film is stored at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) cold storage facility in Lenexa, Kansas. It can only be viewed on request at the cartographic reading room of the NARA Aerial Film Section in College Park, Maryland, more than 1,000 miles away.

The film has to be ordered in person. It can take up to two days to arrive. Only 10 rolls of film are allowed per person. Any copies of the negatives must be photographed on a light table (there are no scanners). The indexing of the negatives is inconsistent and not sequential.

Hammer and Ur have so far identified material between August 1958 and 29 January 1960 - an estimated 46,000 frames from the main cameras and an additional 8,100 frames from the tracking cameras.

“There were dozens of such flights over the Middle East but only 11 of them have so far been declassified” Hammer tells MEE.

What Mission 8648 saw

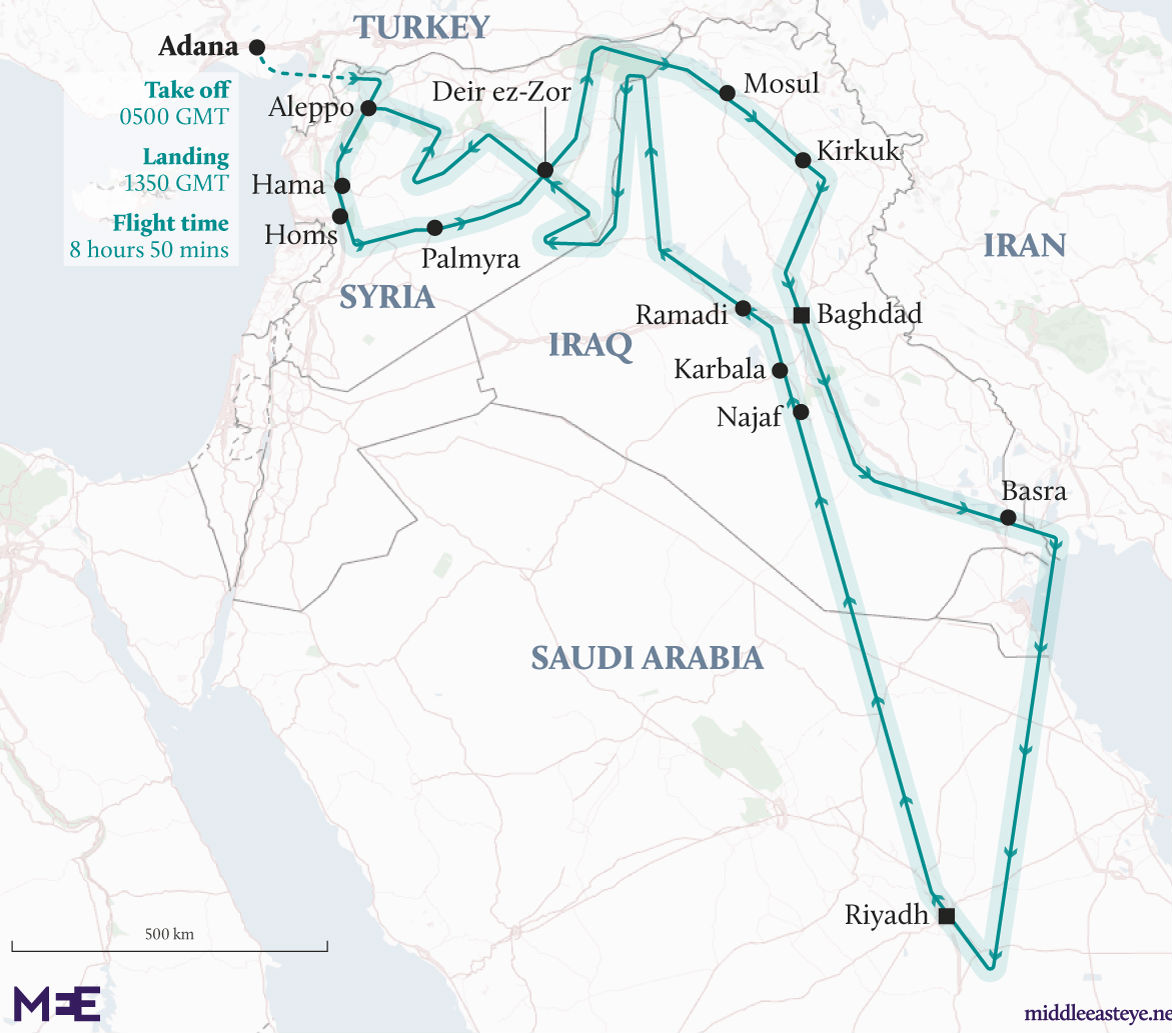

One of these flights is Mission 8648, whose flightpath in October 1959 has been painstakingly pieced together by a team led by Hammer and Ur, using timings on the negatives and other data.

After leaving Turkey at 0500 GMT, Mission 8648 flew over Aleppo, Hama and Homs before banking towards Palmyra. From there it crossed the Euphrates at Deir ez-Zor, then toward the Syrian-Turkish border town of Qamishli.

Then came Iraq and Mosul, Kirkuk, Baghdad and Basra. Next, the U2 headed south to Riyadh before flying back north over Najaf, Karbala and Ramadi.

The mission flew down the Euphrates river valley, with two detours into the Syrian steppe to capture isolated military facilities, then touched down at base at 13.50 GMT.

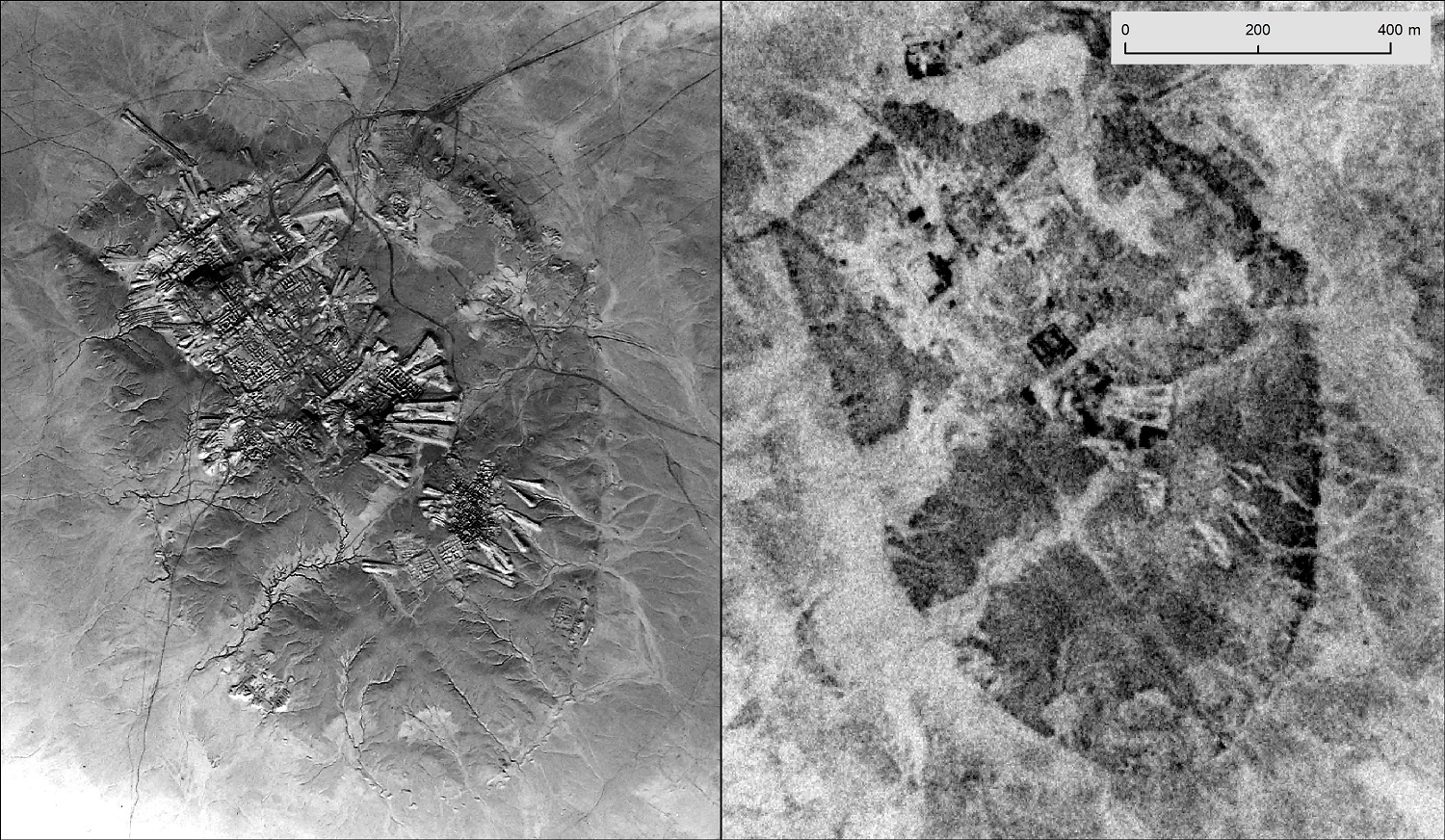

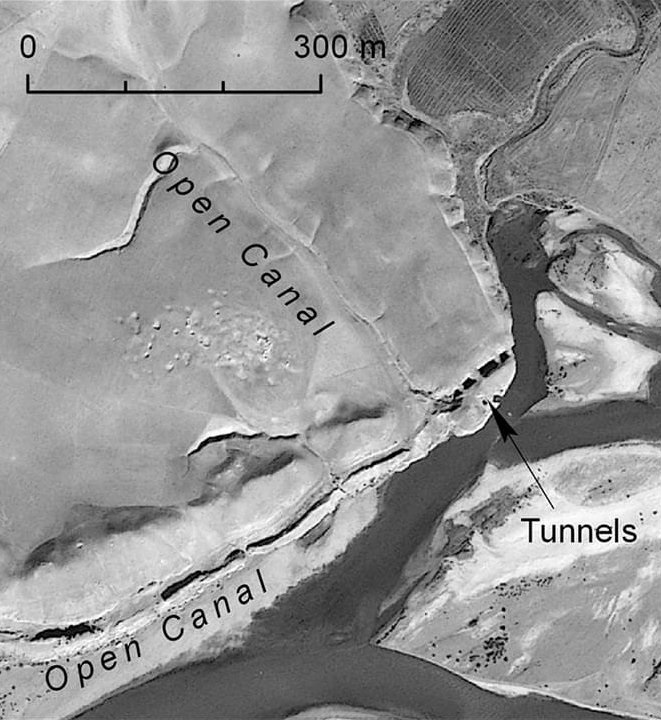

Among the sights it photographed were canals, tunnels and sites at Negub in northern Iraq that are either not visible from the ground or have been destroyed in subsequent decades.

They formed part of the irrigation system that supported the Assyrian city of Nimrud, founded between the 9th and 7th centuries BC, and at the time one of the world’s biggest urban areas.

From this and other aerial photography, experts have been able to assemble a systemic description of how water reached the ancient city.

“The availability of U2 aerial photograph has dramatically enhanced our knowledge of this feature and its operation,” Hammer and Ur wrote in the Advances In Archaeological Practice.

The sights revealed by the negatives have spanned the centuries and given insight into disparate cultures.

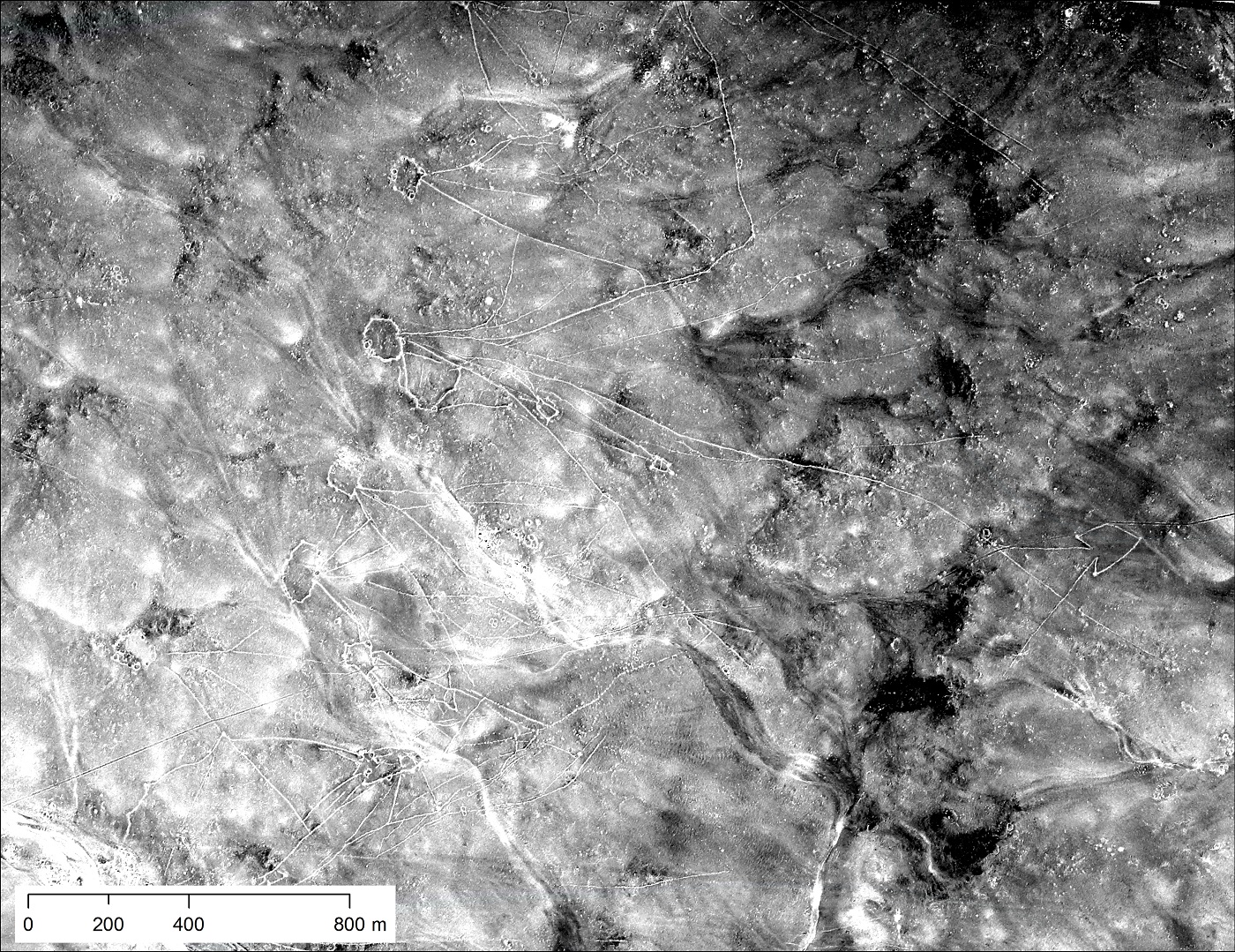

In January 1960, Mission 1554 photographed structures known as desert kites, standing out in the landscape like giant stick figures against the black basalt desert of eastern Jordan.

They are widely believed to have been used by inhabitants of the region between 5,000 and 8,000 years ago to trap gazelle and other large animals.

“Many rock features in the harra are too large and/or faint to be seen from the ground,” Hammer and Ur explain. Other structures nearby resemble the layout of villages or animal enclosures.

Flying over southern Iraq, that same mission documented village structures and population densities among the Marsh Arabs - the communities living in marshlands around the southern Iraq city of Basra.

Since the 1960s their lifestyle has radically changed due to falling water levels in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers caused by dam building in Turkey, Iran and Iraq itself.

There was also the deliberate flooding of the area by the government of Saddam Hussein during the early 1990s as punishment against the Marsh Arabs for their supposed involvement in a failed uprising in 1991.

Many inhabitants of the marshes have abandoned the area as falling water levels and salt intrusion from the Gulf killed their water buffalo and destroyed fish stocks.

“People lived a unique lifestyle there for thousands of years, herding water buffalo, building houses and all manner of things out of reeds, living on floating islands of reeds, planting date palms and fishing,” state Hammer and Ur.

“Now we can study the spatial organisation, demography and lifestyles of these communities.”

Why the U2 spy missions ended

The secrecy surrounding the missions and the U2 - the US military had denied the aircraft even existed - was finally blown apart in May 1960.

A U2 piloted by Gary Powers, an employee of the CIA, took off from Pakistan and, while flying over the USSR, was downed by Soviet missiles (the episode forms the basis of Steven Spielberg’s 2015 drama Bridge of Spies).

US President Dwight D Eisenhower eventually scrapped further missions, including those over the Middle East.

US President Dwight D Eisenhower eventually scrapped further missions, including those over the Middle East.

The incident caused a further deterioration in already tense US-Soviet relations; amid considerable publicity, Powers was put on trial in Moscow. Parts of the crashed U2 plane were exhibited. Powers was sentenced to 10 years in jail but released in a spy swap two years later.

A version of the U2 is still in service today (it also played a key role in the Cuba missile crisis of October 1962, when it photographed Soviet ships heading for the Caribbean). And the power of those images from the height of the Cold War remains.

“It [the imagery] has the potential to become an important resource for the landscape archaeology of Eurasia, as well as an essential tool for the study of urban growth, environmental change and other twentieth century processes," write Hammer and Ur.

Davis says: “Though there are considerable problems accessing and recording the images held in the US, the photographs allow us to see things which don’t exist any more. There’s a huge amount of potential in this kind of work.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].