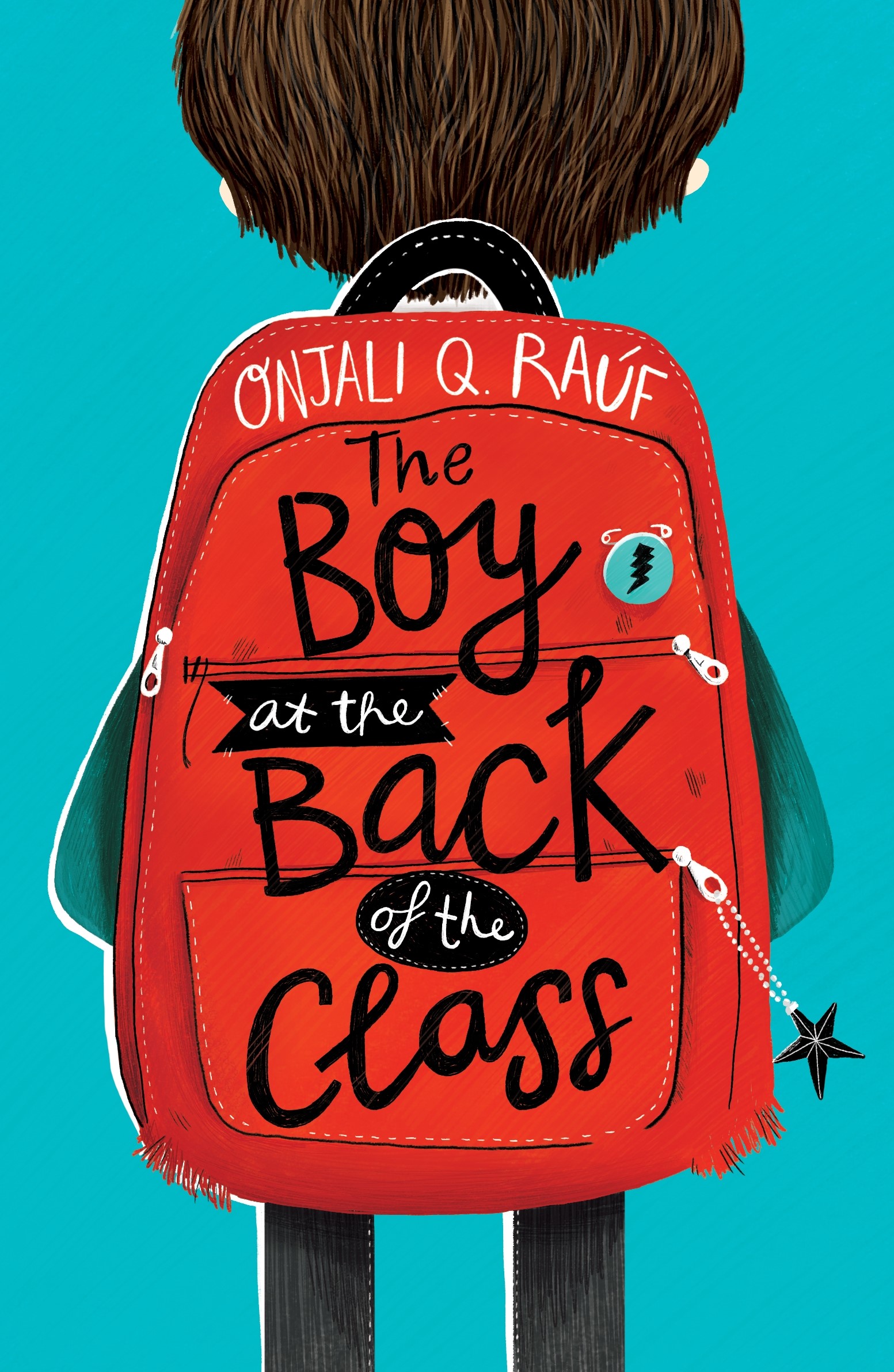

The Boy At The Back Of The Class: Hit children's writer on her story of kindness

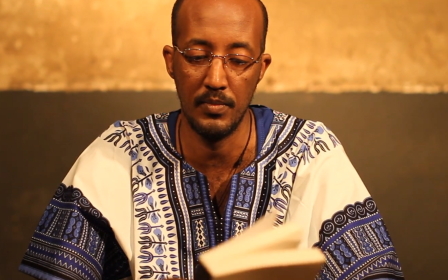

Onjali Q Rauf is surrounded by children, queuing up for her to sign their copy of her debut novel, The Boy At The Back Of The Class.

There are so many of them, it’s taken two hours for the author to meet them all.

Earlier in the day Rauf was on stage at Brighton’s Dome theatre, greeted like a rock star by 1,500 children who had come to see her speak. When she asked the audience if they had all read the novel, the response was a thunderous scream: “Yes!”

In March, The Boy At The Back Of The Class won both the BBC Blue Peter book award and the Waterstones children’s book prize, two of the UK’s best-known prizes for children’s literature. It was also chosen for Young City Reads, a schools-based programme in Sussex, southern England, which promotes children’s reading.

'There’s rubbish and darkness in children’s books as well, but there’s just more fun in the way they deal with it'

- Onjali Rauf

The novel is a page-turning adventure told through a nine-year-old (the child’s name and gender are withheld till late in the narrative), with strong themes of friendship and courage throughout. It is very funny and often moving.

When Ahmet, a Syrian refugee, joins a London school, four friends try to help him reunite with his parents, leading them on an adventure involving the media, hostile politicians and the Queen.

The last few months have been a whirlwind for Rauf. Boy was published in the UK in July – but it wasn’t until later in the year that the messages began. “We started getting an influx of requests from teachers and librarians,” recalls Rauf, “and stuff was happening on Twitter quite a lot, [people] saying: ‘Oh this book is really great for the school,’ and creating resources. And then it really began to snowball.

“I got an email from a parent and he was from a family of a Holocaust survivor. He said this had led to them [the family] talking about this for the first time.”

Women's rights

Rauf is fasting for Ramadan but remains energetic and welcoming, offering biscuits and fruit to all present. She is a powerhouse: a British Muslim feminist who grew up in a council flat in East London. From there she studied literature at Aberystwyth University and then a masters at Oxford.

Rauf’s early life was not typically literary. Her mother loved reading but brought the family up alone while her father was often away working. “We were very poor growing up, we lived in a housing estate in Tower Hamlets, we didn’t have a book in the house that was ours - everything was from the library. I was addicted to [Agatha Christie’s] Poirot.”

She’s a campaigner for women’s rights, and has formed her own charity, Making HerStory, which assists women affected by domestic violence and human trafficking in the UK and overseas.

'Your gift of yourself is the biggest thing you can do. The kids in the book take it to an extreme level'

- Onjali Rauf

Rauf has also been taking aid to refugee support groups in Calais since 2015, where she met Syrian mothers and children whose predicament helped inspire her writing.

Rauf’s own life has had its shocks – and Boy came from one of these.

Two years ago, she was in hospital with endometriosis, a long-term life-threatening condition, and had to undergo emergency surgery. “It was meant to be an hour’s surgery, and ended up being seven–and-a- half hours.”

In pain and on a high dose of morphine, Rauf’s imagination - always stirred by her love of children’s literature - went into overdrive. “I had three-and-a-half months when I couldn’t move, I was bedridden.”

She found herself reading old favourites from her childhood, including Roald Dahl’s Danny The Champion Of The World. Then the idea for Boy novel appeared. “The title popped into my head. I was actually in the third day in hospital,” she says. She excitedly told her mother and began writing. “It wasn’t planned in any way, I just wrote it chapter by chapter.”

Dahl’s work is famously dark, and his influence on Boy is hard to miss. But in Boy, the hostile forces confronting children come from the harsh 21st-century world rather than giants, witches or a chocolate factory.

For Rauf, children’s stories are a perfect way to explore reality’s harsher themes. “There’s rubbish and darkness in children’s books as well, but there’s just more fun in the way they deal with it.”

Act of friendship

Rauf’s descriptions of school life in the book are based on her own experiences, but she says otherwise it is not autobiographical. But the protagonist’s determination to help those in need is much like her own.

“The message hopefully is friendship. You have the power to be a friend to someone who is in need, whoever that person might be. Your gift of yourself is the biggest thing you can do. The kids in the book take it to an extreme level.”

Going to Calais every four to six weeks to provide aid to frontline refugee organisations gave her an insight into the lives of those made homeless by war, and formed the basis for Ahmet, the boy in the book’s title.

“For me, he is the every child of the refugee children that I met,” she says. “His withdrawal, his quietness. Because if you go to the camps it’s quite eerie sometimes how the children that haven’t been there long don’t respond, not as a child should do, which is kind of laughing and playing.”

Ahmet’s gradual reaction to friendship, his opening up, is all drawn from what Rauf saw in the camps.

Family trauma

Rauf is familiar with the worst that family trauma can inflict. In 2011, just as the then 24-year-old was finishing her masters in Women’s Studies at Oxford, she received terrible news: Mumtahina Jannat, her aunt, had been murdered by her abusive husband.

Ruma, as Rauf called her, had left her husband in 2005. Rauf and her mother had helped her rebuild her life independently - but in 2011, Ruma’s ex broke into her flat and strangled her. This terrible event sparked Rauf launching Making HerStory, to help those affected by domestic violence.

'I didn’t expect anything like this to happen to me in my life, even though it’s a dream come true'

- Onjali Rauf

Since she has gone public with her aunt’s story, many others from the Bangladeshi community and beyond have come forward with their own experiences of abuse. Ruma’s case exposed, Rauf says, how none of the public services involved - GPs, police, children’s services - talked to each other. “None of the information is shared, and when a woman goes to court she doesn’t have anything to back her up, but they’ve got the information [on file].”

Rauf began fund-raising for women’s refuges through a book club, set up in her aunt’s name, which then evolved into the charity in 2012. The motto? “Whatever we can do, wherever we can do it.”

She previously trained to be a teacher, and as part of her charity work she visits schools to talk about domestic violence and misogyny. Soon the charity work became her full-time job, until her illness struck.

All the while she was writing. “I’d been wanting to be an author for a very long time.”

The two parts of her life are like completely different worlds, says Rauf. “You’ve got one side which is this, it’s lovely, it’s kids and you’re talking about a children’s book, and on the other side you’ve got a world where you are talking about human trafficking, domestic violence and what you can do to stop that.“

But a reading of The Boy At The Back Of The Class makes clear that the idea of helping the most vulnerable whatever way you can is the driving philosophy of Rauf, the writer and the campaigner.

Feminist exclusion

Rauf has also spoken about the challenges of being an openly Muslim feminist in the context of what she sees as a suspicious white feminist mainstream in the UK.

She describes attending a recent feminist conference, where the panellists were talking about diversity. “Then this woman on the panel said: ‘What is this with all these so-called Muslim feminists coming out’ and the whole audience laughed. I was the only Muslim woman in the room, it made me so angry and I had to leave. You are laughing about this, do you not want us on your side?’

'I was the only Muslim woman in the room, it made me so angry and I had to leave'

She refutes this stereotyping and othering of visibly religious feminists, not just Muslims, by much of the white feminist movement. “Even before you can join them in the fight, you have to fight for your place in the fight. That’s really tiring, constantly having to negotiate or debate or justify your presence as a feminist and a fighter for women’s rights.”

On the strength of Boy, Rauf was signed for a two-book deal with publisher Orion. The second novel, The Star Outside My Window, is due out in October, and tackles the issue closest to her heart, domestic violence. “It sounds really heavy when I put it like that, but it involves a brother and sister who go on a hunt to change something about the star that is really important to them, and their mum and what’s happened to her.”

She admits to nerves about her second novel, which brings together her campaign work and her creative life.

“The reaction to this [Boy] has been so unprecedented and I didn’t expect anything like this to happen to me in my life, even though it’s a dream come true. So the pressure of the second book is a little bit high.

“Nothing is really separate now, it’s all interlinked.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].