Lost in music: How Palestine's forgotten songs got rebooted

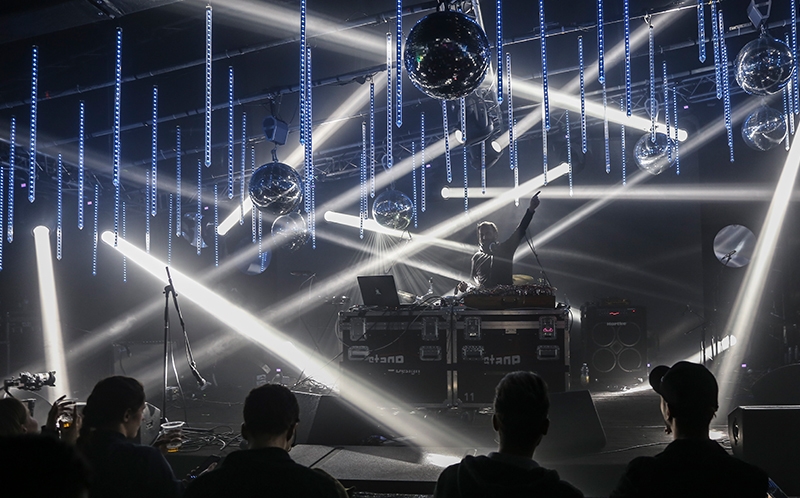

They gathered in an apartment in Ramallah for two weeks - a diverse group of musicians and DJs brought together for a unique project.

They included DJ and producer Sama Abdulhadi, Nasser Halahlih, a pioneer of 2000s electronic music, and Muqata'a, the godfather of Ramallah's hip hop scene.

Their task? To compose and record Electrosteen, an album based on a huge, painstakingly collected audio archive of Palestinian folklore.

“The experience was very unique for me,” says Halahlih, 37, who lives in Haifa, Israel and stayed in Ramallah for the sessions. “I knew all the people there but never worked with them on music. It was also very special because we shared the house for two weeks."

"I knew about these recordings but never thought they would be available.”

Electrosteen is intended to celebrate Palestine's rich musical heritage, giving a new lease of life to rarely heard traditional music while celebrating the burgeoning electronic scene.

The artists use songs made available by the El Funoun Dance Troupe, a cultural organisation which has preserved and revived Palestinian folk music since the 1970s.

Through the workshop, Halahlih and six other Palestinian musicians collaborated on 18 tracks, some of which were performed at the Paris Institute du Monde Arabe in March.

An independently produced CD and DVD box set is due out soon: three tracks are already on Spotify.

Heritage scattered

Music is central to Palestinian life and heritage. But during the past 70 years, due to the Israeli occupation and conflict, much of that cultural history has been lost and neglected. Yet it can still be found in villages and towns across the Israeli-occupied West Bank and among Palestinians living in Israel.

'That archive is extraordinary: it is something like 200 CDs and DAT tapes'

- David McDonald, University of Indiana

There are no official institutions dedicated to archiving music in Palestine, which makes information and documents scarce. The closest official effort were the archives of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), but these were destroyed or looted during the conflict with Israel or scattered across that several countries that the Palestinians found themselves in during the past half-century.

During the 1990s, some NGOs and Palestinian grassroots organisations tried to collect the lost music of Palestine. One of them was the Popular Art Centre (PAC), a leading cultural body in Palestine. Founded in 1987, it is a sister organisaton of El Funoun, and soon began to amass a sound archive.

David McDonald, an ethnomusicology professor at the University of Indiana, who used the archives for his research, says: “At that time there was this great effort with Palestinian folk music, nationally engineered.

“The purpose of it was to search for a unique Palestinian sound that was different from Jordan or Lebanon. Many villages were recorded.

“That archive is extraordinary: it is something like 200 CDs and DAT tapes, with descriptive materials and even transcriptions.”

Since PAC embarked on its project, a generation not only of musicians, but also of historians, sound engineers and archivists have discovered layer upon layer of Palestinian music across a variety of musical styles and locations; from classical Arab music to alternative rock, from Haifa on the Israeli coast to villages across the occupied West Bank.

What music gets saved?

The Electrosteen project comes at a time when Palestine has seen a growth in labels, studios, and global recognition.

There are new venues, such as Kabareet in Haifa; international exposure for projects like Palestine Music Expo in Ramallah, a showcase for new artists now in its third year; and Palestine Underground, a documentary made by the London-based streaming project Boiler Room.

Halahlih himself, with fellow keyboard player Isam Elias, launched Zenobia, a band incorporating Palestinian music and folklore.

It’s part of a new globalised Arabic sound that also numbers the likes of shamstep pioneers 47 Soul; the Paris-based electronic group Acid Arab; king of French-Algerian electro-Maghreb, Sofiane Saidi; and Ammar 808, led by Tunisia’s Sofyann Ben Youssef.

Like all the participants involved with Electrosteen, it was the first time Halalhih had access to such a store of previously inaccessible material, although sampling old back catalogues was not entirely new to him. “Even before Zenobia, I did some work with [traditional] Arab music, but more for films and theatre,” he says.

The growing interest in archival work has also shed a light on the earlier efforts of the PLO toward Palestinian cultural preservation - and its limitations.

For McDonald, the PLO era from the 1960s to the 1990s was overly selective when it came to music. “It created bands and dance groups who would perform at its rallies, then record cassettes that were sent everywhere and played on the radio. They had a propagandist view.”

Moreover, music was secondary when it came to archives, he says. Until the turn of the century, the main focus was on films and historical documents deemed to embody Palestinian identity.

Nader Jalal knows only too well the problems with preserving Palestinian musical heritage: he was director of arts at the Ministry of Culture under the Palestinian Authority from 2004 to 2011.

"I hate us,” he says. “To be honest, I really hate us. I asked many leaders: ‘Are we convincing the world that we are just… villagers in Palestine?’ I like folklore, but where are the cities? Where are the muwashah?” (Muswashah is sung poetry and one of the most prestigious forms of traditional Arab music.)

“We were only interested in folklore, dabkeh,” he says, critical of the focus that the PA archive placed on traditional Palestinian music and dance over modern, popular and urban Palestinian forms.

Only recently did Jalal realise there was something just as important that was lying, forgotten: key composers and musicians from pre-1948 Palestine. “I only discovered it nine years ago," he says. "All these forgotten musicians - Rawhi al-Khammash, Mohammed Ghazi.”

Now retired, Jalal is a key figure in Nawa, whose goal is to rediscover orchestral and recorded Arab music made in 20th-century Palestine.

The archives that the project has gathered since 2004 from around the world are played by Nawa’s in-house band. Old recordings are re-issued, while new releases are made from forgotten sheet music.

Nawa’s work tells another narrative of Palestine, of a cosmopolitan pre-1948 entity.

“Palestine was on the map," he says. "[Renowned Egyptian singer] Oum Kalthoum, when she went to Syria, she made a concert or two in Jaffa [the biggest Palestinian city during the British mandate], and vice-versa for all the musicians coming from Iraq and Syria to Egypt. Haifa! Jaffa! Jerusalem!”

Mohamed Abdel Wahab, another legendary Egyptian singer, one of the first Middle Eastern songwriters to combine Arabic and Western musical styles, came to Jerusalem two or three times a year during the 1930s and 40s. He was recorded by the Near East Broadcasting Station, one of the radio stations founded by the British under the Mandate.

Nawa calls for nothing less than a reassessment of what music is in Palestine. Loab Hammoud, a musicologist, oud player, and key member of Nawa, says: “If you say Palestinian music, it must have a special character... A music that talks about Palestinian issues, the land, Nakba, people who leave, refugees.

“As such, this is a music that [includes] even Lebanese singer Marcel Khalife, or Moroccan band Nass el-Ghiwane, made in the 1970s.”

Hammoud says that much of the music that came from Palestine is part of the regional soundscape, and comparable to the finest of its time. “You cannot say that the muwashah composed in Aleppo is Syrian, and that a muwashah composed in Cairo is Egyptian."

For Jalal, this reassertion of Palestine’s musical wealth is not chauvinism. “I am not saying that Palestinian musicians were better than the others," he says while pointing out that they were professional artists, geographically located at the region’s crossroads, who were dispersed across the region after the state of Israel was founded in 1948.

“Take Sabri al-Sharif, who was at the Near East Broadcasting Station, Jalal says. "After 1948, as the radio was moving to Cyprus, he was told about two guys, Assi and Mansour Rahbani [legendary composers in Lebanon]. He was the director and ideas-maker of their projects until the 1970s.”

Online: How to revive the past

Aside from Nawa, PAC and the likes of the Edward Said Conservatory of Music, there is also a growing effort by individuals and smaller projects to put Palestinian music online and make it available to new audiences.

Palestunes, a Soundcloud channel which opened in 2018, has already aggregated more than 3,829 tracks. There are even more on YouTube, where individuals have digitised and shared old tapes.

The quality is variable: there is also a lot to sort through. But read between the lines and you can gain a sense of the fractures and upheaval that Palestinian musicians have endured since 1948.

Take, for instance, old footage from a band called Shatea, which means "beach" in Arabic. During the 1990s, it included bassist Raymond Haddad, who came to attention at the Palestine Music Expo in 2018 with his own solo electronic set.

“In 1988, at our first gig, we expected 60, 70 people,” he says of the performances held in a Haifa cinema due to a lack of venues. “And boom! One thousand, two thousand people came, man. After that we toured, we made two albums. We led the way.”

Haddad is part of another layer of Palestinian cultural history: the music of Haifa, made by the “48ers” - Palestinians who live in Israel - after the First Intifada, inspired and influenced by the uprising in the West Bank and Gaza.

This “new” scene is now almost 30 years old and is already creating its own history, with musicians more at ease combining the traditional and modern, including folk, rock and electronica.

“When I started music, I played [legendary Lebanese singer] Fairouz, yes," says Haddad, "but I played Pink Floyd.

“There is nothing special, it’s like anyone at 14, you grab an instrument and you play what you like.”

'When I started music, I played Fairouz, yes... but I played Pink Floyd'

- Raymond Haddad

Like other bands around the world, Shatea sung about everyday teenage life – except that in Palestine it was always over-shadowed by politics and occupation.

Once dubbed the “pioneers of Arab rock”, the band split in 1995, briefly reuniting for one show in 2004. Haddad says there are plans to document the group’s legacy. ”We have documents, photos, a lot, we are talking about a documentary in the near future,” he promises.

And so the desire to archive comes full circle, as the rock of the past two decades, as well as hip hop and millennial electronica is itself archived and preserved.

But genres intersect, especially in a small state like Palestine where most musicians know one another. Electronica fuses with the archives of PAC. The likes of Nasser listen to and play Arab classical music. Orchestra members trained at the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music appear playing pop at the Palestine Music Expo.

Buds of future music

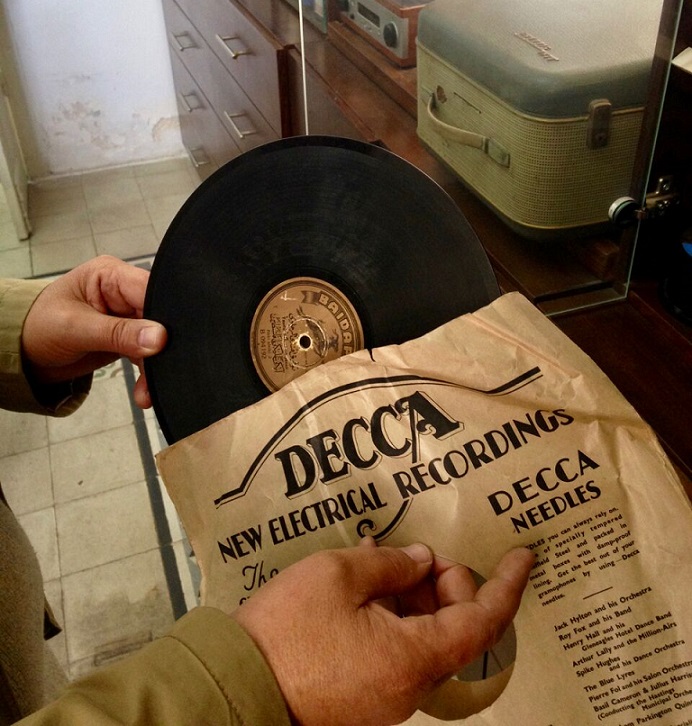

Back in Ramallah, at the headquarters of Nawa, Jalal is rummaging through a drawer from which he retrieves a bag and triumphantly exhibits a studio tape.

“This is the first album from Al Bara'im (The Blooms). It took me six years to lay a hand on it.” He pauses. “The first rock band in Palestine." They group started in Jerusalem in 1966.

They, like so many others, are long disbanded, although a reissue may be on the way. The search for Palestine’s musical heritage goes on, tape by tape, song by song, even as the music itself gains worldwide recognition that for so long has been denied.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].