Khashoggi killing: Seven points you may have missed in the UN's report

United Nations human rights investigator Agnes Callamard released her long-awaited report on the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi on Wednesday.

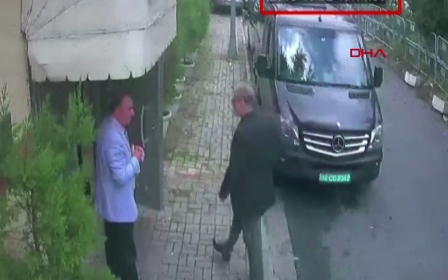

Over nearly 100 pages, Callamard provides the fullest public account to date of the journalist’s final moments before he was killed by a team of Saudi operatives inside the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul on 2 October.

Her main conclusion? There is credible evidence linking Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to the murder.

But the report, whose credibility has been called into question by one Saudi minister, has many more details worth highlighting. Here are seven we found:

1. Sanctions aren't strong enough

Callamard welcomes the fact that the US, and then subsequently Canada, the UK, France, Germany and the EU, took the initiative to sanction individuals for their role in Khashoggi’s murder. But she takes them to task for failing to explain why certain people were targeted - particularly low-ranking Saudi officials - and not others, like Saud al-Qahtani, one of the alleged masterminds behind Khashoggi’s murder.

She’s not questioning the use of sanctions in response to his killing, Callamard says, but “it is difficult to escape the impression that these particular sanctions against 17 or more individuals may act as a smokescreen, diverting attention away from those actually responsible”.

But even more critically, she says that the sanctions against individuals are not strong enough, namely because they don’t “correspond to the gravity of the crime” and don’t actually address the fact that Saudi Arabia, as a state, is ultimately responsible.

What would be strong enough? Well, Germany, she points out, is the only western government to suspend arms sales to Saudi Arabia. And then she says she endorses recommendations made earlier this year by a UN special rapporteur that governments stop licensing the sale of surveillance technology to Saudi Arabia until the kingdom can show it is using that technology lawfully.

This will certainly raise questions in the UK. The issue of how British-made surveillance equipment is used once purchased has been under scrutiny after it emerged earlier this year that it was possible that UK technology sold to the United Arab Emirates was used to monitor British academic Matthew Hedges.

Hedges was accused of spying based on information extracted from his electronic devices and held in solitary confinement for more than five months. In November, he was jailed for life only to be pardoned and released five days later.

2. Guterres should stop waiting on Turkey

Callamard urges the United Nations' Human Rights Council, Security Council or Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to demand a criminal investigation into Khashoggi’s murder. She says what Saudi Arabia has done so far is insufficient and has violated international human right standards.

She particularly zeros in on Guterres - without using his name. It has been argued - she doesn’t say by whom - that the UN secretary-general must wait for Turkey to make a formal request before initiating an international criminal investigation. Sure, she says, it would be great if Turkey or even Saudi Arabia would ask for one, but “it would be absurd to limit the intervention of the UNSG to such scenarios”.

“The secretary-general himself should be able to establish an international follow-up criminal investigation without any trigger by a state,” she concludes.

3. Immediate threats to residents in four countries

Callamard commends Saudi Arabia for restructuring its intelligence services in the wake of Khashoggi’s killing, but says repeatedly that the kingdom hasn’t changed its behaviour and continues to detain journalists and political activists even in recent months.

Specifically, she says she has received credible evidence that the CIA has notified four western countries of “foreseeable and immediate threats” against residents who fled Saudi Arabia or another Gulf country that goes unnamed.

Presumably, one of the countries she’s referring to is Norway where Iyad al-Baghdadi, a rights activist and outspoken critic of the crown prince, said authorities told him in April that he faced an imminent threat to his life from Saudi Arabia. Baghdadi told MEE that he had "a hunch" it was the CIA who tipped off the Norwegians. But Callamard doesn’t name the countries or individuals.

4. Could the CIA have done more?

Early on, the special rapporteur says that, based on the information in front of her, there is “insufficient evidence” to suggest that Turkey or the United States knew or could foresee the threat to Khashoggi.

But further in, she cites an October 2018 Washington Post report which said that US intelligence agencies had intercepted communications between Saudi officials discussing plans to abduct Khashoggi. Callamard also points to a February 2019 article in the New York Times which reports that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman told a top aide in a 2017 conversation intercepted by US intelligence agencies, that he would "use a bullet" on Khashoggi if the journalist didn’t return to Saudi Arabia and stop criticising the government.

She says she wasn’t able to substantiate the reports, based on intelligence leaks, and highlights that the communications were reportedly only transcribed and analysed after Khashoggi’s murder. Still, she says “trigger words” - like bullet or abduction - that can only suggest violence “should have been picked up, prioritised and analysed".

The UN investigator asks whether CIA analysts would have concluded that Khashoggi was under threat if the intercepts had been analysed sooner. She concludes that she can’t assess that based on “the limited information available regarding the wording of the intercepts”.

“However, at the very least, such a threat should have triggered further investigation into its credibility and immediacy. Such assessment, in turn, would require evaluating whether the identity and activities of Mr Khashoggi put him at risk, and whether there were systemic patterns of violence against individuals like him,” she says.

5. Khashoggi statue

Callamard suggests, among a list of suggested symbolic responses to Khashoggi’s murder, that Turkey or the city of Istanbul erect a Khashoggi memorial, standing for press freedom, right in front of the Saudi consulate where he was killed.

“The special rapporteur has been able to ascertain that there is enough space for such a statue,” she writes.

6. The mystery company

Qahtani, one of the architects of Khashoggi’s assassination, has been behind a relentless campaign to target critics of the Saudi government online.

In her report, Callamard says experts consulted for her inquiry have raised the role played by lobbyists, PR firms and media outlets who, contracted by the Saudi government, individuals or companies, have protected the reputation of the kingdom abroad.

“The work of one company in particular was mentioned for the monitoring and analysis of social media they undertake to help identify messages and messengers critical of Saudi Arabia,” she says, without elaborating.

7. Turkish issues

Callamard goes into great detail about the difficulties Turkish authorities went through to get access to investigate the Saudi consulate building and the consul-general's residence. A public prosecutor tells her it was “like anger management because [the Saudis] didn’t let us conduct an inquiry. We had to push and push to be allowed in”.

Still, she takes a swipe at Turkey’s own human rights record. The prosecutor tells her that the country is preparing to hold a trial to air the evidence held by authorities.

But she raises concerns that the country’s legitimacy to deliver justice to Khashoggi is “seriously weakened” by its “repeated and widespread arbitrary detentions, and unfair trials, of journalists and others on the basis of their exercise of their right to freedom of expression”.

This article is available on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].