Gaza: How the Palestinian enclave has been strangled

Isolated from the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. Under siege for more than a decade. Subjected to internal political discord. Gaza plays the most complicated of roles in the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Its position both as the stage for a catastrophic humanitarian crisis and as the seat of power for Hamas - the Palestinian armed resistance group labelled a terrorist organisation by Israel and its allies - has made Gaza's fate central to any talks seeking to properly address the future of Palestinians.

Done deal: How the peace process sold out the Palestinians

+ Show - HideMiddle East Eye's "Done Deal" series examines how many of the elements of US President Donald Trump's so-called "deal of the century" reflect a reality that already exists on the ground.

It looks at how Palestinian territory has already been effectively annexed, why refugees have no realistic prospect of ever returning to their homeland, how the Old City of Jerusalem is under Israeli rule, how financial threats and incentives are used to undermine Palestinian opposition to the status quo, and how Gaza is kept under a state of permanent siege.

-

Annexation: How Israel already controls more than half of the West Bank

-

Refugees: How Trump’s ‘deal of the century’ is doomed to failure

-

Jerusalem's Old City: How Palestine's past is being slowly erased

-

Gaza: How the Palestinian enclave has been strangled

-

Financial aid: How dependency on donors leaves Palestinians trapped

But Gaza is in a bind. Humanitarian relief, economic development and Palestinian self-determination are all too often viewed as mutually exclusive in peace plans - and that includes US President Donald Trump's "deal of the century".

Egyptian rule to Israeli siege

Gaza’s status as an enclave tucked between Egypt and Israel has since the creation of the Israeli state defined much of its existence as well as the stakes at play.

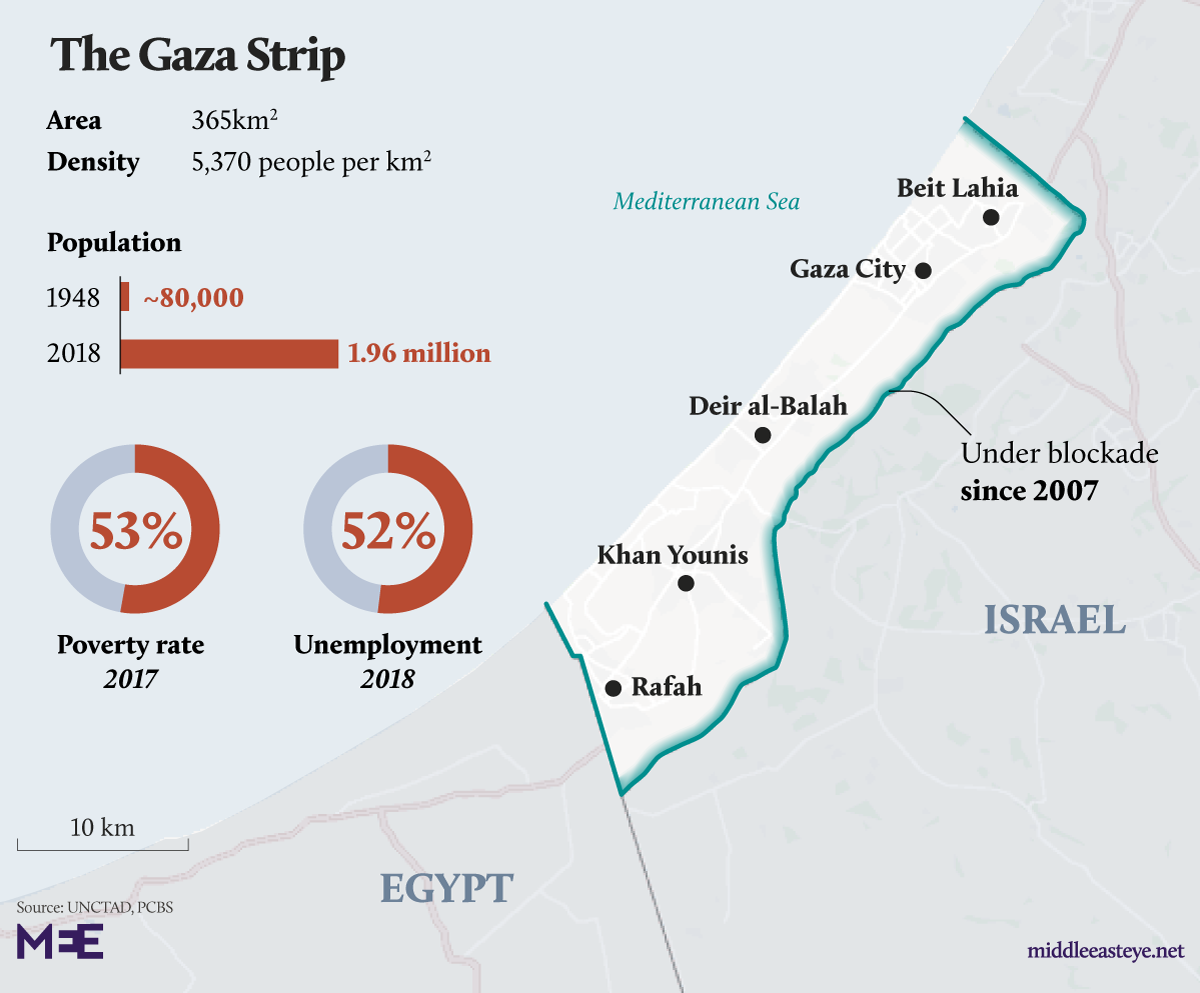

In 1948, the Gaza Strip counted some 80,000 inhabitants - but that number quickly rose to an estimated 200,000 as Palestinian refugees fled Israeli forces. Sixty years later, Gaza has nearly two million residents and a reputation as being one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

In the late 1940s, Gaza was ruled by the Egyptian military, with a brief stint of largely symbolic self-governance, before it was occupied by Israel following the Arab-Israeli war of 1967.

As with the West Bank and East Jerusalem, Israel set up settlements across the Strip in contravention of international law. It was in this context that Hamas emerged as an armed offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood during the early days of the First Intifada in 1987.

While the 1993 Oslo Accords planned for a full Israeli withdrawal from Gaza over a five-year transitional period, this part of the peace deal - like much of the rest - failed to materialise. It was only after the Second Intifada ended in February 2005 that Israel evacuated its 25 settlements in Gaza: 9,000 settlers were moved out later that year.

Hamas won the 2006 legislative elections, but soon afterwards conflict erupted between it and Fatah, the ruling party of the Palestinian Authority (PA). The feud has effectively left Gaza under a Hamas-led administration, separate from the Fatah-run PA in the occupied West Bank.

As Hamas secured control of the Strip, so Israel imposed a stringent blockade on Gaza that has also been upheld by Egypt on the enclave's southern border.

Israel no longer has a permanent military presence in Gaza but continues to exercise control. Access to electricity hovers between three to 12 hours a day. Fuel shortages regularly threaten the functioning of essential health infrastructure. Clean water has become a rare commodity. More than one million people live on $3.50 or less a day. The sea, once a vital source of income for Gaza residents, is subject to ever-changing restrictions on sailing and fishing rights.

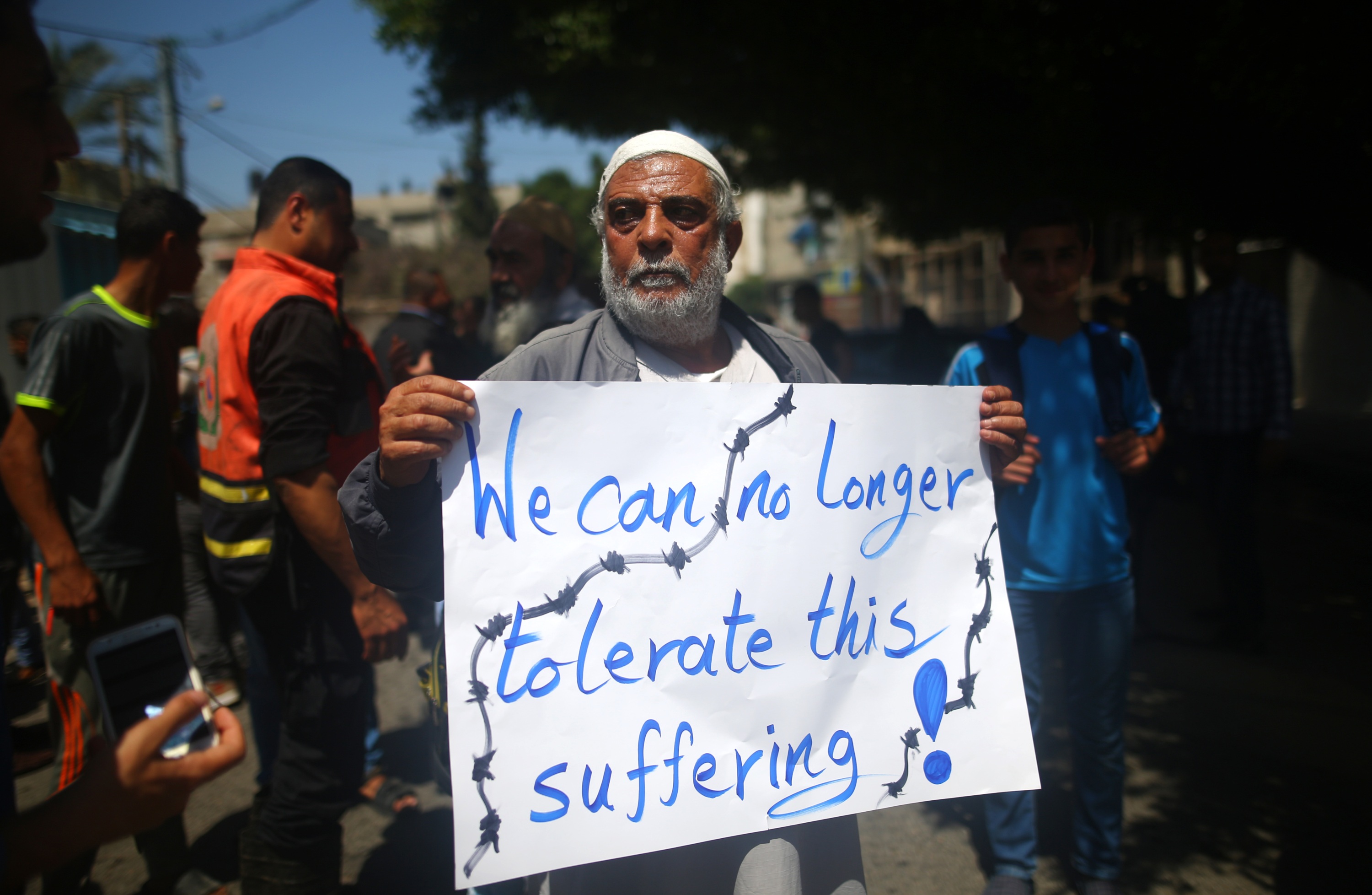

Twelve years of siege, coupled with three wars, countless flare-ups, and the repression of a mass protest movement since 2018 have led the United Nations to repeatedly warn that Gaza has effectively become "unliveable".

Palestinian unity breaks apart

Since the 2006 Palestinian elections, Gaza's fate has been caught between two seemingly irresolvable conflicts: that between Palestinians and Israelis, and that among the Palestinians themselves.

The PA wants to consolidate political power in the occupied territories, but Hamas is wary that it will be sidelined under a unified government. Disagreements also persist between Fatah and Hamas on what attitude to adopt toward Israel, not least regarding the future of Hamas's military wing.

This 13-year old political fracture has also affected the likelihood of any credible, long-term diplomatic mediation between Israel and Palestine. How can any effective discussions about Palestinian statehood take place when the Palestinian leadership itself is bitterly divided?

Countless attempts at reconciliation - hosted by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Syria - have all collapsed. But the failure of these talks is not only due to irreconcilable differences between the two Palestinian parties. Israel has much to gain from continued intra-Palestinian discord, and it has often applied military and financial pressure when rapprochement between the Palestinian sides seemed within reach.

In 2011, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu responded to a unity deal signed by PA President Mahmoud Abbas and Hamas's then political bureau chairman Khaled Meshaal by calling it a "a mortal blow to peace and a big prize for terror". Israel then suspended the transfer of $80m in taxes it collects on behalf of the PA.

On 2 June 2014, Abbas swore in a technocratic Palestinian unity government led by Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah. Ten days later, three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped in the West Bank. Israeli forces launched an intensive manhunt, blaming Hamas for the disappearances: their bodies were found two weeks later.

In late July, Israeli police said that the abductions and murders were carried out by a "lone cell" - but, by that point, Israel and Hamas were three weeks into a devastating war in Gaza that left more than 2,000 Palestinians and 70 Israelis dead.

Some observers believe that the search for the teenagers and subsequent crackdown on Hamas were merely a pretext to derail Palestinian unity efforts and, consequently, Palestinian statehood.

A future in Sinai?

There are no signs of a lasting reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas - so where does this leave Gaza?

The enclave's especially sensitive status - isolated between two unsympathetic governments of Netanyahu and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and dealing with a humanitarian crisis of catastrophic proportions - has prompted many mediators to try and address its issues separately from broader discussions about Palestinian self-determination.

In 2015, former UK prime minister Tony Blair met on several occasions with Meshaal - the first time Hamas was the primary Palestinian representative in any talks.

Blair reportedly offered Hamas a full lifting of the blockade on Gaza, aid for reconstruction after the 2014 war, and the possibility of a seaport and an airport. In return it would have to agree to an unlimited ceasefire with Israel. Ultimately, however, Blair failed to obtain Israeli and Egyptian backing for his plan.

In late 2018, reports emerged that, as part of the "deal of the century," Washington and Israel were pressuring Egypt to turn parts of northern Sinai region into an industrial and infrastructure zone to employ Palestinians and benefit Gaza.

The Trump administration has denied the plan - but it would not be the first time that the idea has been floated.

In the 1950s, UNRWA, the United Nations agency for Palestinian refugees, proposed that Gaza's overpopulation could be relieved by expanding the territory southward along the coast between the Egyptian towns of al-Arish and Port Said - a plan that was categorically rejected at the time by Palestinian refugees.

Two decades later, Israel tried to persuade Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat to fully annex Gaza to Egypt following the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, Palestinian journalist and researcher Adnan Abu Amer told Middle East Eye.

However historical, the isolated approach to Gaza in talks has not been to everyone's liking. For Saeb Erekat, the secretary-general of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), efforts to negotiate a truce between Hamas and Israel just as Israel was carrying out punitive measures against the PA was deliberately "accentuating the [intra-Palestinian] separation in all possible means" in an attempt to "destroy the Palestinian national project embodied in the creation of the independent and sovereign Palestinian state".

Financial plans fail

Meanwhile, Gaza's urgent need for economic and humanitarian relief have long been a focus for peace conferences and talks - but rarely acted upon.

According to Abu Amer, plans for economic development in Gaza were raised in 1991 during the Madrid peace conference. The Oslo Accords of 1993 called for oil and gas cooperation between Israelis and Palestinians to support Gaza's industry. Abu Amer told MEE that plans for a petrochemical factory in Gaza were seen as a core element in cementing the economic future of a planned Palestinian state.

During the Oslo Accords, plans were proposed for a factory, a seaport and an airport in Gaza: of these, only the airport materialised. Inaugurated by then-US president Bill Clinton in 1998, the Yasser Arafat International Airport was short-lived: by 2000, it had been destroyed by Israeli forces during the Second Intifada.

Plans for a seaport have been regularly suggested, including by Israeli politicians. But so long as the Israeli siege, including its ban on the import of "dual-use" products such as construction material into Gaza, remains, economic initiatives can only ever be theoretical.

While Israel has been primarily responsible for maintaining Gaza in a state of humanitarian crisis, even Israeli figures have seen the danger of an increasingly impoverished and unsustainable Palestinian territory.

In September, it was reported that Israeli security officials had urged their government to find an alternative source of aid for Gaza. It was feared that Trump's decision to halt US funding to UNRWA could worsen the enclave's humanitarian situation, which could descend into an all-out war.

Meanwhile, far-right politicians in Israel, who have gained influence in recent years on the Israeli stage, have called for a "hard and disproportionate" military intervention against Hamas.

With conditions deemed unliveable by international organisations and an impasse in talks between the PA and Israel, the future for Gaza and its two million inhabitants seems grim.

- Motasem Dalloul contributed reporting from the Gaza Strip.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].