Netflix and the Middle East: How Jinn became a nightmare

Few TV shows in the Middle East have generated as much intense vitriol as Jinn, Netflix’s much-hyped first Arabic series.

Past TV dramas made in the Arab world have stoked anger by their treatment of controversial themes, including antisemitism (Horses Without A Horseman, 2002, from Egypt); depictions of the Prophet Muhammad’s companion (Omar, a 2012 co-production); and women’s guardianship and the row with Qatar (Saudi series Selfie, which began in 2002).

But Jinn, a Jordanian production, has been greeted with near-unanimous negative reviews and widespread censure from public institutions and Islamic groups in the kingdom since its release in June, chiefly for a tame kiss and overt foul language which many believe presents an unrepresentative view of society.

The controversy has revealed a patriarchal Arab society, torn between antiquated tradition and modernity - and failing to organically settle in either.

The state prosecutor, the kingdom’s mufti, the media regulatory body and the Authority of the Petra Region all attacked the show for breaching public morality, saying that it did not represent Jordan’s values and traditions. The Muslim Brotherhood said that granting permission for the show to stream in Jordan was “a terrible crime” that “incites the wrath of God” for “including scenes of obscenity that violate the values of Islam”.

The reaction beyond critics has been exaggerated and, in the case of the Islamist groups, downright hypocritical given their static, rigid view of Islam is no different from that of the “orientalist, cultural invader”, as one Jordanian journalist put it. The reaction across social media was also scathing:

https://twiter.com/maiurie/status/11393489148284Although it has not been without its defenders:

Artistically, the criticism is well deserved. Jinn is a badly scripted, poorly acted and sloppily directed series about high-school kids mixed up with the supernatural.

But it also marks a grave misstep for Netflix, the world’s biggest streaming service, which is attempting to enter the Middle East market, raising questions about how seriously it wants to create original and worthwhile content for the region.

Netflix looks to expand

Netflix, which grew out of a DVD video service, now has an estimated 148m subscribers worldwide, a hefty share of global streaming audiences. In recent years it has been keen to commission its own content, not least given how licensing fees studios such as Warner Brothers and Disney (which now owns Fox and launches its own service later this year) have increased.

Netflix has invested heavily in content acquisition and production in the US, but has not been as shrewd overseas. At its heart it is still an American-centric company, whose pitches and projects from local staff suffer US oversight, from character developments to plot details.

Some shows have been criticised for a lack of understanding of non-US culture. Narcos, a quasi-biopic about drug lord Pablo Escobar, was globally popular but angered many in Colombia due to its blunt and stereotypical portrayal of the country. Equally contentious is Filipino drama, Amo, a gritty chronicle of president Rodrigo Duterte’s lethal war on drugs, that essentially sides with the police forces who have killed more than 5,000 civilians so far.

Netflix has made inroads in the Middle East: with 1.7 million users, it has the region’s largest paying subscriber base. But it faces competition. Starz, the Dubai-based Middle Eastern subscription video on demand (SVOD) service, reached the 1 million subscriber milestone this year.

US streamers such as Amazon Prime are expanding their reach in the region. And all are dwarfed by the 70 million users of Shahid, Saudi TV network MBC’s free video-on-demand service.

But Netflix’s acquistion fees – the amount it pays for licensing films and TV shows - in the region are significantly less than the large sums paid by Saudi conglomerates Rotana, MBC and ART, which own the exclusive rights to the Middle East's biggest productions.

That’s because despite substantial gains in recent years, MENA is a small if promising market when viewed globally. It explains some of the odd choices amid Netflix’s regional content, including obscure low-brow Egyptian comedies such as Aman Ya Sahbi (2017) and poverty porn pieces like The Republic of Imbaba (2015).

Netflix’s first original releases in the region met with a mixed reception. Adel Karam: Live from Beirut (2018), a recording of a Lebanese stand-up comedy special, was dimwitted and misogynistic. The Protector, a Turkish fantasy series, was formulaic and inconsistent, but its faults were swept under the rug by the energetic and imaginative direction of young horror wonderkid, Can Evrenol.

Instead, Netflix succeeds in the Middle East through its global brand and cultural cachet. Its original drama productions are popular: many are illegally pirated through rampant downloading.

Filmmakers and TV producers in the region have seen the streaming service galvanise TV elsewhere and waited for it to arrive on their doorsteps. Would Jinn be the boost they needed?

The devil in the detail

Jinn was heralded as the Arab TV event of the year: a high school supernatural drama starring a group of first-time actors and set in Jordan. It was directed by Lebanese Mir-Jean Bou Chaaya (behind acclaimed action comedy Very Big Shot) and Jordanian Amin Matalqa (director of Sundance hit Captain Abu Raed). The writers were Nashville-born visual effects gurus-turned producers, Elan and Rajeev Dassani.

“We’re delighted to be working with such a variety of breakout talent to launch our first Arabic original series in the Middle East,” said Erik Barmack, VP of International Original Series at Netflix in February 2018. “We are extremely excited to bring this story to a global audience, and to celebrate Arab youth and culture.”

But anyone who had been paying close attention to Netflix’s moves in the region was not exactly holding their breath, certainly once they got beyond the press releases.

Bou Chaaya may have showed potential in Shot but was largely untested. Matalqa’s subsequent features after Abu Raed all flopped, while the Dassani brothers had nothing in their filmography remotely related to Arab culture.

It was clear that the makers of Jinn intended to provoke a reaction

The choice of Jordan as the setting for Jinn was always going to be problematic. Despite the commendable efforts of the Royal Film Commission, the country’s film and TV industry is still very much in its infancy, held back by its shallow pool of creative talent and limited resources.

Only one bona-fide local talent has emerged during the past couple of decades: Yahya Alabdallah of The Last Friday (Theeb’s Oscar-nominated Naji Abu Nowar is British-born and educated).

At the same time, the moderately conservative nature of the country, coupled with an absence of inherent film culture, makes it hard for storytellers to determine where the boundaries lie.

But it was clear that the makers of Jinn intended to provoke a reaction.

Scary movie?

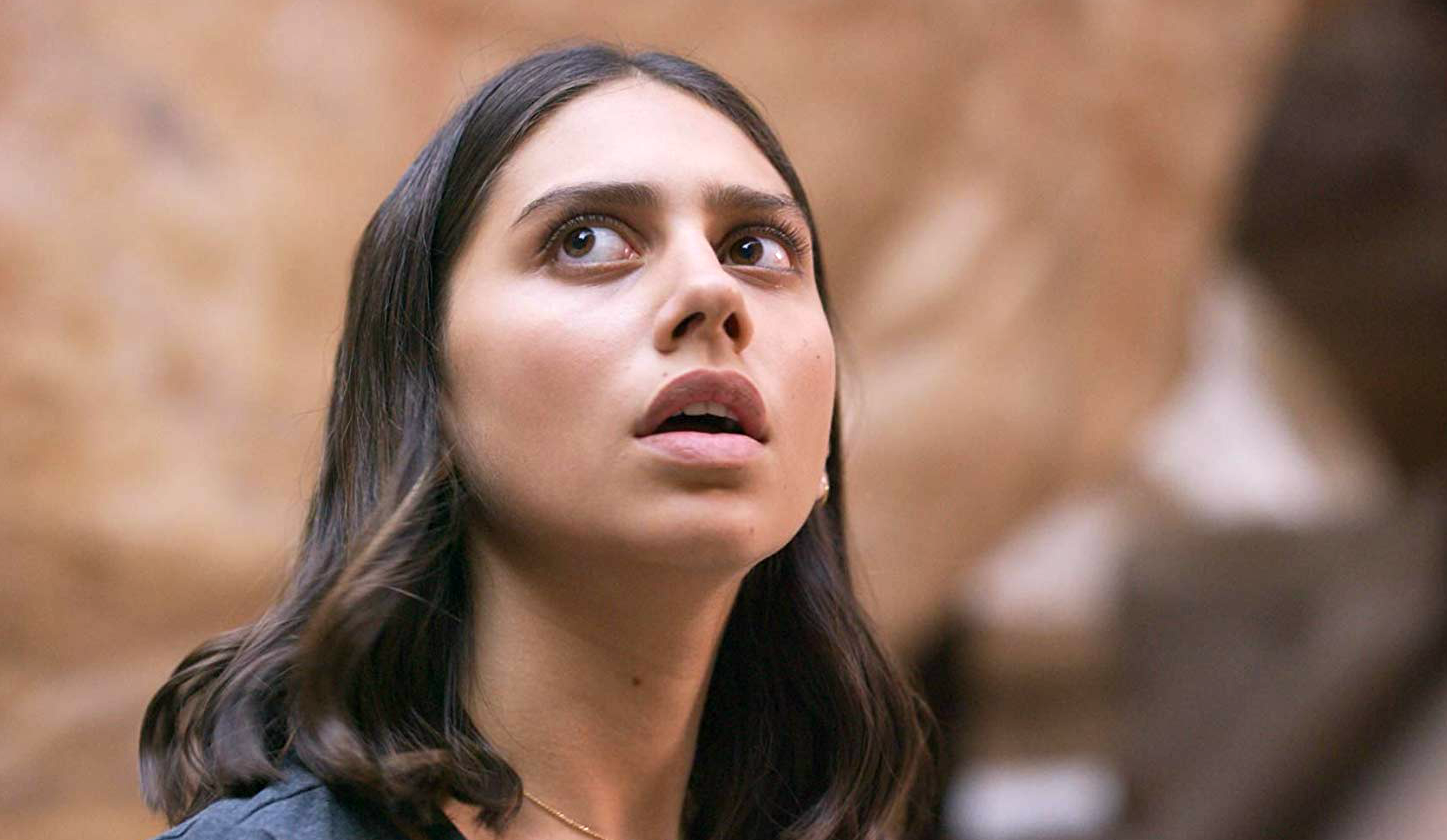

The five-episode series begins with a school trip to where else but Petra, Jordan’s world-famous archaeological city. Mira (Salma Malhas) is a quasi-rebellious teenager still grappling with the loss of her mother, while supportive to her grieving father. She is dating Fahed (Yasser al-Hadi), a cocky, tepid douche who spends the larger part of the series trying to control his on-and-off girlfriend.

Mira, Fahed, and the rest of their clan are all financially well-off, unlike hapless middle-class Yassin (Sultan Alkhail), who is bullied by every person in his life. When bully leader Tarek (Abdelrazzaq Jarkas) pushes him into a pit and pees on him, help comes out of nowhere in the shape of Vera (Aysha Shahaltough), a mysterious student who swiftly become his avenging angel.

In episode one, Tarek is mysteriously killed, beginning a series of involuntary self-attacks, murders and strange happenings in the school. A young man called Keras (Hamzeh Okab) suddenly appears to Mira and explains that the clueless kids have accidently summoned the jinns, a breed of otherworldly creatures who invade the bodies of humans when they’re called out.

Who exactly are the jinns? Are they fallen angels, ghosts or something in between? How are they summoned exactly? All of these questions remain unanswered, for the world of Jinn is no different than the Amman that the kids inhabit: characterless, lacking in detail and reminiscent of American suburbia. It amounts to a hodgepodge of cliched teenage drama tropes, terribly predictable folkloric scares and blatant touristic advertorials for Jordan’s tourist sites.

Everything in Jinn feels like a carbon copy of tired American formulas

The problems don’t just stop at the shoddy writing or the wooden acting or the English-language dialogue that has been sloppily translated into Arabic.

Jinn is a lazy, by-the-numbers drama with no real insight into Jordanian teenage lives, no position on modern Jordanian society and no redeeming artistic vision.

Bou Chaaya and Matalqa show no knack for directing actors and fail to convey their characters’ existential ennui in a country grappling with a sense of identity. They briefly touch upon class, but never fully explore the subject.

Everything in Jinn feels like a carbon copy of tired American formulas, including the basic arcs of the characters and their inner conflicts, their relationship with one another; and even the brand of horror that blends the grisly with the supernatural. Nothing feels authentic, emotionally real or believable.

The curse of Jinn

Jinn is superficially transgressive - but would it have triggered such hateful reaction had it actually been good? Some Jordanian intellectuals commended the cast and crew for confronting Jordan’s conservative social norms (while admitting that it is badly scripted).

The first taboo Jinn broke was kissing. On-screen smooching is not exactly novel in most of the Arab world but it is usually avoided in TV, even when the subject matter is straightforwardly sexual (which is not even the case with Jinn).

The scene of Mira French-kissing her boyfriend has stoked controversy and resulted in Malhas being extensively bullied and shamed on social media. In a statement on Twitter, Netflix MENA said that it regretted the "current wave of bullying against actors and staff in the Jinn series".

The second red line crossed was the use of bad language. Jinn features language as explicit as kol khara (“eat shit”) and sharmoota (“whore”) which, while prevalent in some English-language TV, has never been heard before in Arab productions.

Amid the uproar, some Jordanians criticised what they regarded as the hypocrisy behind the attacks:

But Jinn has an inherent problem which is hard to ignore. If the real intention of the showrunners was to shake up Jordanian society, then they would have paid attention to creating three-dimensional characters with real pains.

They would have explored Jordan’s real problems, including class, freedom of expression and identity, or even evoke them by using the jinns themselves as social metaphors.

But there is no political subtext in Jinn, nor tangible social commentary, nor thorough exploration of the family dynamics. Instead of challenging, subverting or sidestepping the default Hollywood narrative, Jinn ends up reaffirming it.

The failure of Jinn is inexcusable. Arab TV has witnessed a great evolution during the past two decades, proving that major talents do exist in the Middle East. With Jinn, Netflix has shown a clear ignorance of a region it has yet to grasp, casting doubt over its future plans and artistic strategy.

In a statement to Middle East Eye, Netflix said: “Jinn seeks to portray the issues young Arabs face as they come of age, including love, bullying and more. We’ve heard from many members across the Middle East and around the world how much it has resonated with them. But we understand that some viewers may find it provocative and as always will listen to that feedback as we invest more in local Arab content for the region.”

Attention will now focus on the network’s next major Arab releases.

First will be Al Rawabi School for Girls, which will be directed by Jordanian Tima Shomali and produced through her company Filmizion Productions. Shirin Kamal is the writer on the project, which Netflix has said is a "story of how a bullied girl gets revenge on her bullies, only to find out that no one is all bad, and no one is all good, including herself".

There is also horror series Paranormal, an adaption of the work by Egyptian cult novelist Ahmed Khaled Tawfik, which have sold more than 15m copies. It will be produced by veteran producer Mohamed Hefzy and directed by Amr Salama, a competent commercial filmmaker, if not a visionary, whose indistinctive American style would perfectly fit in with the Netflix brand.

As for Jordan, one hopes that the controversy swirling around Jinn will encourage the country’s storytellers to break more taboos and tell the untold stories of their young nation. Whether they possess the necessary tools to realise that dream, however, is a different issue.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].