Syrian refugees in Turkey: What you need to know

As soon as the 2011 protests against the rule of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad were met with state repression, Turkey became a haven for those fleeing the crackdown and ensuing civil war.

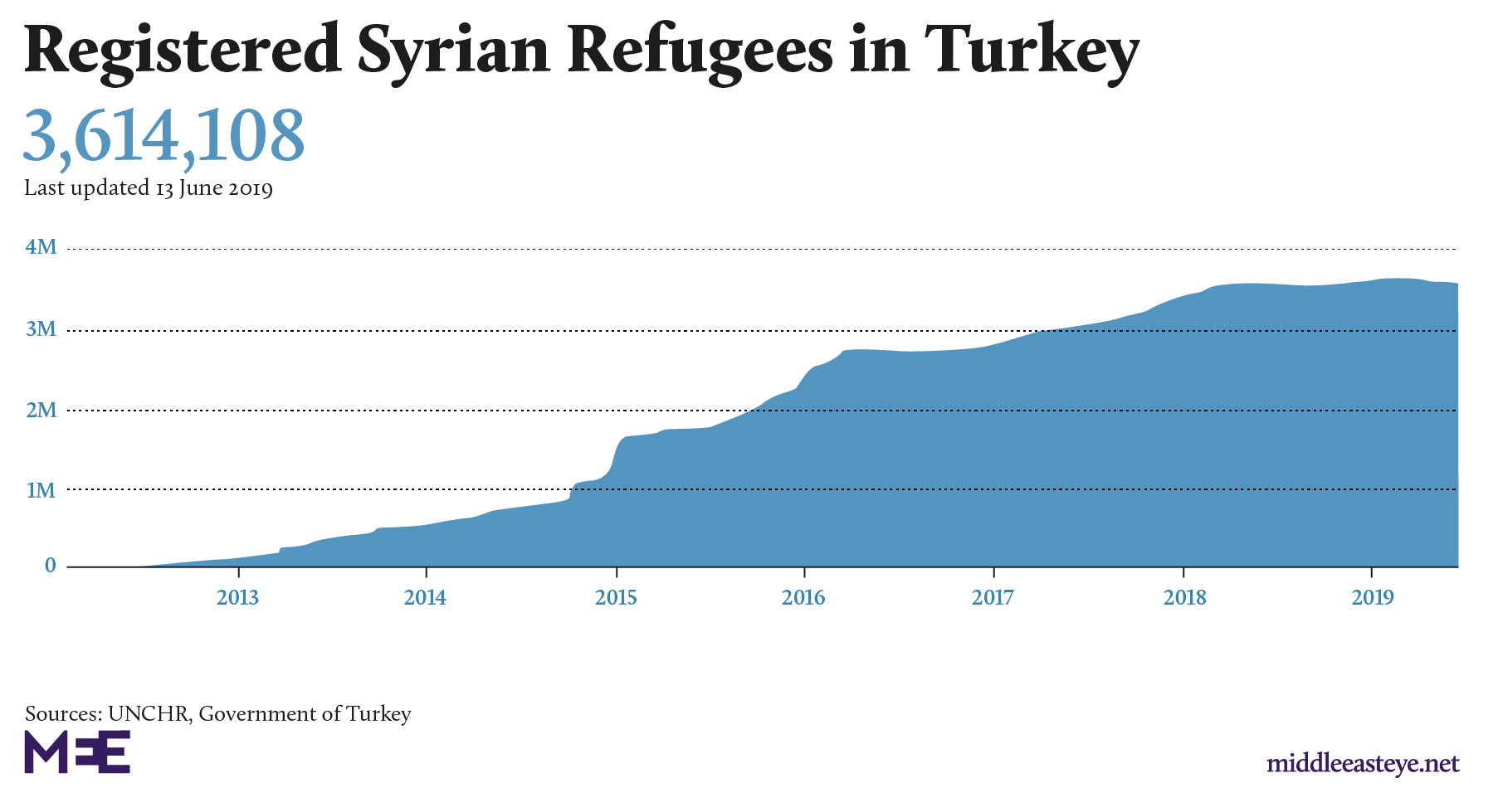

Eight years later, Turkey is host to the world's largest refugee population. According to the UN Refugee Agency, there were 3,614,108 Syrians refugees living in the country in May.

However resentment and violence towards Syrian refugees has increasingly made headlines in recent years. A video released on social media this week showed an anti-Syrian riot in the Kucukcekme district of Istanbul on Sunday following false reports that a Syrian had sexually harassed a Turkish girl.

A similar incident took place in the suburb of Esenyurt in April.

The presence of so many Syrians in the country has stoked tensions. Many Turks (and Kurds) claiming that the refugees have pushed down wages and put strains on housing and jobs, while others complain that the appearence of Arabic lettering and other Syrian cultural signifiers throughout the country has diluted Turkey's national identity.

What is the legal status of refugees in Turkey?

Turkey only officially recognises refugee status for Europeans. None of the Syrians currently residing in the country are recognised as refugees and have instead been referred to as "guests" by the government, recognised under what's called the temporary protection (TP) regulation.

Signatories to the 1951 Geneva Convention - which sets out how soldiers and civilian should be treated in war - were allowed a "geographical limitation" which Turkey opted for. This means that only those fleeing events occuring in Europe are given refugee status.

Despite their lack of rights under the Geneva Convention, Syrians are often still referred to as "refugees" by government officials and the media.

Legislation passed in 2013 and 2014 granted Syrians in Turkey a right to healthcare and education in line with the Geneva Convention.

However, Syrians who wish to work in Turkey are required to apply for government permits, rather than having an automatic right to work as those covered under the convention.

As of November 2018, only 32,000 registered Syrian refugees under temporary protection had such permits. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands (perhaps more) work informally in Turkey for low pay in poor conditions.

In addition, the Turkish state has the right to terminate temporary protection at any time.

What do Turks think?

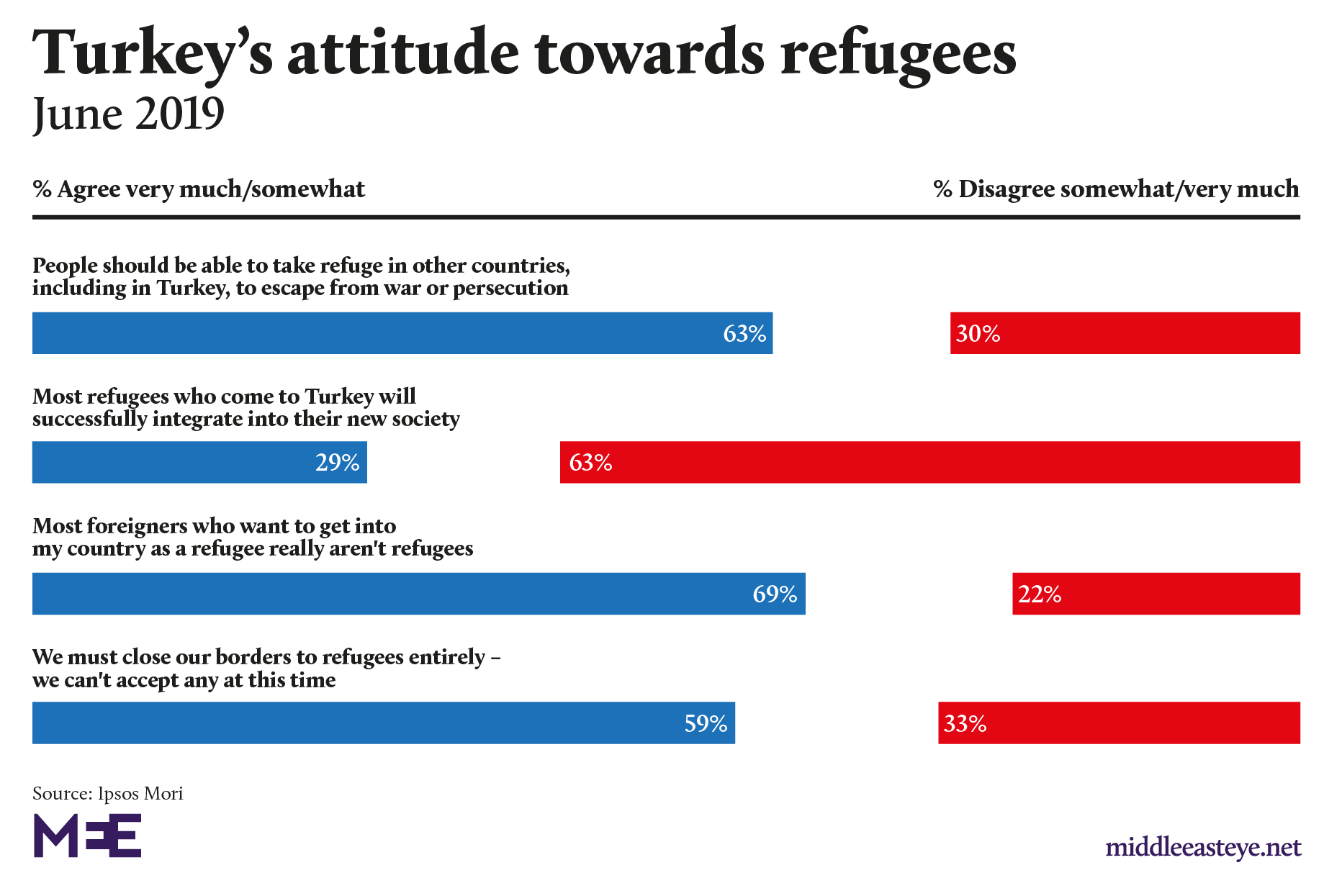

A global attitudes survey released in June by Ipsos Mori showed that 59 percent of Turks - the highest percentage of any country except India - agreed with the statement: "We must close our borders to refugees entirely – we can't accept any at this time."

Turkey also scored second-highest (69 percent) for the statement "Most foreigners who want to get into my country as a refugee really aren't refugees."

Sixty-three percent disagreed with the statement "Most refugees who come to Turkey will successfully integrate into their new society."

On the statement, "People should be able to take refuge in other countries, including in Turkey, to escape from war or persecution", however, 63 percent agreed.

What are the political parties' positions on refugees?

Justice and Development Party (AKP)

The AKP and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had long championed Turkey's status as a haven for Syrian refugees - the Turkey-Syria border was highly porous until 2014, allowing refugees to flee easily into the country. In 2012, Erdogan told Syrians fleeing into Turkey to regard his country as their "second home". He has also promised to naturalise hundreds of thousands of Syrians - although so far only 75,000 have become citizens.

In recent years, however, the AKP's tone has shifted on Syrian refugees. As ethnic tensions have mounted, the party's support base has increasingly joined the rest of society in viewing the presence of Syrians in Turkey negatively.

The party's leadership has shifted its rhetoric, downplaying suggestions of permenancy for the refugees. Erdogan has repeatedly framed Turkey's military operations in northern Syria, particularly in the previously Kurdish YPG-controlled Afrin, as a precursor for returning Syrians home (albeit not to their original homes).

In late June, Erdogan said the number of Syrians returning would reach one million once safe zones had been established and, while campaigning for the 23 June re-run Istanbul mayoral elections, AKP candidate Binali Yildirim was keen to emphasise that Syrians in Turkey would "return home" and warned that he would take tougher action against Syrians committing crimes.

Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu also issued an order on 20 June for all signs written in Arabic in Turkey to be taken down and replaced with Turkish language ones.

People's Republican Party (CHP)

Turkey's oldest party has opposed permenant settlement for Syrian refugees, though the party's different wings - for years largely split between Turkish nationalist and social democratic tendencies - have been at odds on a number of issues.

In the party's 2018 manifesto, the party promised to ensure "the safe and gradual repatriation of Syrian refugees under temporary protection in Turkey without being victimised" following a "peaceful solution in Syria".

In the wake of the original March elections, several punitative measures enacted by newly elected CHP mayors hit the headlines: the mayor of the western Bolu province announced he would be cutting aid to Syrian refugees and promised he wouldn't "give a single penny to Syrian refugees from the Bolu Municipality budget", while another mayor in western Izmir promised to "get rid of Syrians".

In constrast, Ekrem Imamoglu, the winning mayoral candidate for Istanbul who was lauded for his inclusive language, largely avoided the subject during the campaign, apart from mentioning a plan to create a "special unit to address the Syrian refugee crisis in Istanbul".

Speaking to Haberturk TV a few days after his victory, however, he warned that Syrian refugees "threatens people’s income" due to being unregistered and warned that Turks needed to "protect our people’s interests".

In another interview, he complained about the number of Arabic-language signs in Istanbul and warned that the city's "own culture is disappearing". He added, however, that Syrians required "support" and that he would "be a mayor who acts with humanity and never with racism".

His victory in the election campaign also coincided with a "Syrians fuck off!" hashtage trending on Twitter.

Nationalist Movement Party (MHP)

As Turkey's most popular ultra-nationalist party, the MHP has been fiercely xenophobic throughout its history and has strongly opposed any attempts to permanently settle Syrian refugees. The party's leader, Devlet Bahceli, said in 2016 that it was a "national duty" for Syrians to return to their country once it was safe to do so.

Some analysts suggested that one reason for the AKP's loss of its majority in June 2018 - and the MHP's apparent rise from the ashes in the same elections - was as a result of right-wing voters decamping to the MHP over its hard-line stance on Syria refugees.

Peoples' Democracy Party (HDP)

The left-wing, pro-Kurdish party has long had to deal with conflicting attitudes to the presence of Syrian refugees. In the past, former co-leader Selahattin Demirtas (currently imprisoned) has called for the "guest" status to be abandoned and for Syrians to be granted official refugee status with the "right to education, healthcare and employment" that comes with it. The party's official policy in its 2018 manifesto also promised to give non-Europeans refugee status.

Among the party's Kurdish base in the southeast, however, tensions have been high in a region that has long been impoverished and afflicted with conflict and displacement.

As the area with the largest concentration of Syrian refugees, fears have risen about demographic changes - a popular theory among Kurds persists that Erdogan was settling an increasing number of supposedly loyal Syrians as a solution to the "Kurdish problem" in the wake of renewed violence between 2015 and 2017.

HDP officials have made similar claims about the AKP's Afrin resettlement plan, which they described as a "war crime".

How are Syrians treated?

The experience of Syrians in Turkey has been mixed.

Numerous articles have appeared since 2011 detailing the success of various Syrian entrepreneurs, businessmen and shop owners.

A report by the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey said that nearly 7,000 enterprises had been opened by Syrians in Turkey since 2011, employing around 100,000 people.

Successful stories of integration and harmony have also been highlighted in border towns with a high concentration of Syrians such as in Gaziantep and Kilis.

However, many Syrians have also complained of heavy-handed tactics by the government, and hostility from locals.

A deal agreed between the EU and Turkey in 2016 saw the former paying the latter to take back refugees who attempt to cross illegally into the EU. The deal has been condemned by human rights bodies as illegal under international law.

Amnesty International has also documented refugees being detained and forcibly returned to war zones, while Human Rights Watch has documented refugees being repeatedly shot at and killed by Turkish soldiers on the border with Syria.

What happens next?

Despite the many promises from politicians to return Syrians to their homeland, many fear that a new wave of refugees could be on the horizon if a long-mooted operation is carried out by Assad to rout the last remaining Syrian rebels from Idlib province.

The province is currently home to around 3 million people with no where left to turn in a Syria that has largely been recaptured by Assad and his allies. Fearing reprisals from the government, many would flee to the Turkish border.

Speaking on the subject last month, a Turkish Interior Ministry official said Turkey did not "have any more space left for a new migration wave" and warned that a "political solution" and a "political transition" was needed to prevent this happening.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].