Arab poet Mourid Barghouti: Watching the leaves fall

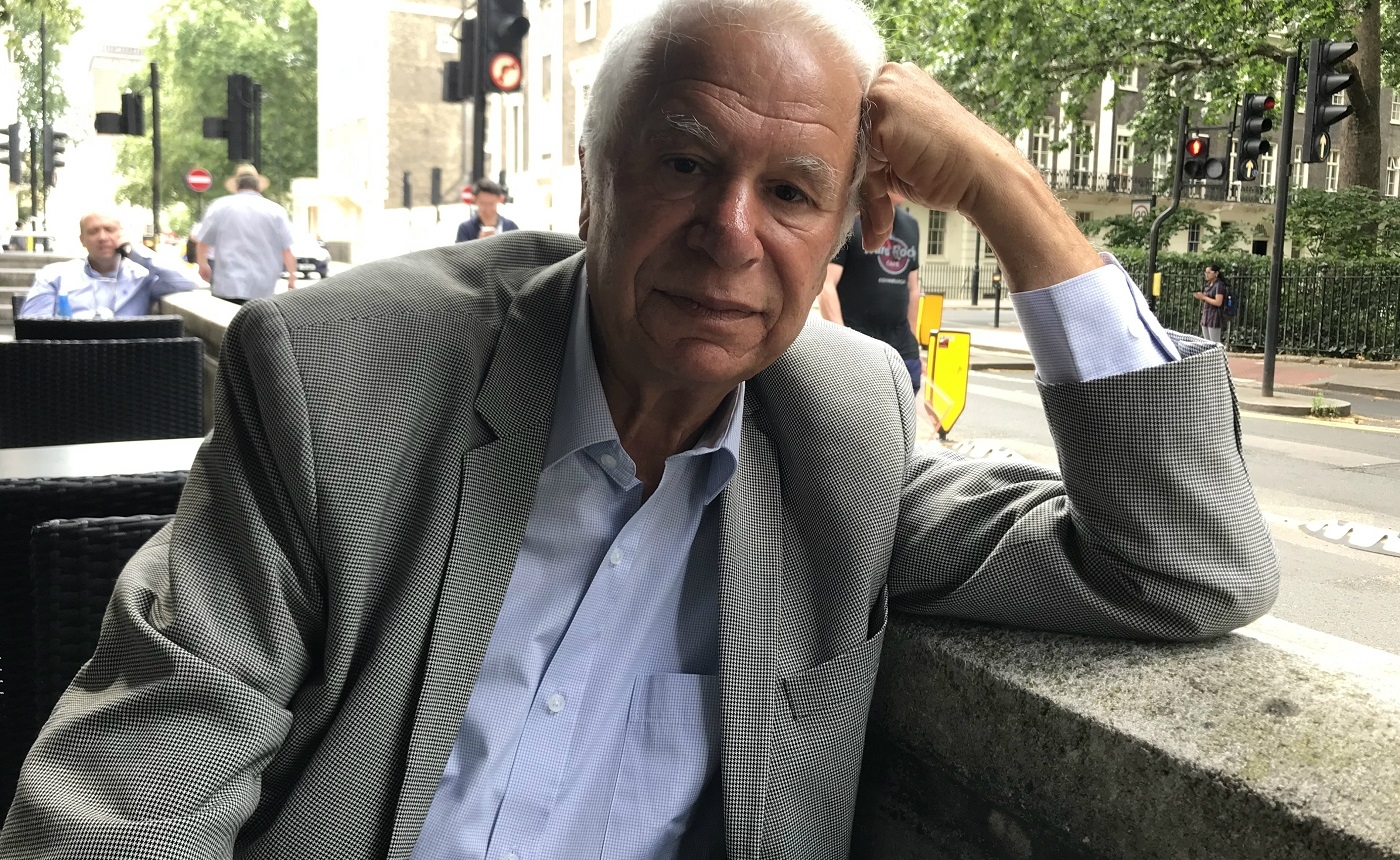

The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti has sold his soul to poetry. His verses, travels and visions are all about the art of writing a poem.

Today he’s sitting on a hotel terrace opposite Russell Square in London’s Bloomsbury district, renowned for its literary and academic heritage. He sips orange juice and draws on a cigarette.

"I can't do an interview without smoking," he says, refusing a request to change seat to avoid the roaring noise and dusty breeze of central London.

He has been here before. "I used to come to London to visit museums, libraries and some friends, and since 2005, to read poetry and for work," he recalls.

Barghouti is touring the UK to read from The Obedience of Water, which was included in A New Divan: A Lyrical Dialogue between East and West, an anthology published by Gingko that brings together 24 poets from Europe, the Middle East and North America to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s masterpiece West-Eastern Divan.

His verse is picturesque, writing as if using a camera lens in various angles and positions, utilising the senses to present a gallery of images and generate feelings.

Barghouti’s poems tackle intimate stories and metaphors of love, homeland, childhood and family, but also open up to catch the macro meanings of life.

"I gave everything to poetry, which is the centre of my life. All my travels, writings and readings are about poetry," he says.

In the footsteps of Goethe

Barghouti was born in 1944 in Deir Ghassaneh, near Ramallah. He had just graduated from Cairo University, where he majored in English, when Israeli troops occupied the West Bank during the summer of 1967 following the Arab-Israeli war. He was barred from returning to his hometown, which was now freshly under military occupation.

A decade later, Egypt's then-president Anwar Sadat ordered Barghouti to leave the country, along with other non-Egyptian intellectuals, on the eve of his visit to Israel in 1977. The poet headed for Beirut, then left there in 1981 for Budapest, where he lived for 13 years. He returned to Egypt in 1994 to be reunited with his wife and son.

"I defend my intellectual independence, and I am against the idea of pledging allegiance to politicians," he says. "I have a problem with both totalitarianism and opposition factions, with pro- and anti-regime newspapers. First and foremost, the poet has to be close to his true self, and not close to any cultural or political scene.

"I have lived in 46 houses, in three continents, and left them against my will," Barghouti says. "I don't attach myself to places, because I'm afraid I would leave them. I live in time not in places, and I write most of my poems during winter."

Nowadays, he has two addresses, one in Beirut and the other in Amman. Barghouti belongs to a generation who rejuvenated and refreshed the themes and subjects of Palestinian poetry, from national and screamy slogans to the intimate, micro poetry, that captures the life of Palestinians as humans.

He has published a dozen poetry collections, as well as two prose masterpieces: I Saw Ramallah, about his trip back to his home town Deir Ghassaneh after 22 years of exile; and I Was Born There, I Was Born Here, which is about another a trip to Palestine, this time with his poet son Tamim Barghouti, who has a rock-star audience and is watched on YouTube by millions. The two parted when Tamim was only a few months old and his father was forced from Egypt.

For A New Divan, Barghouti contributes The Obedience Of Water, translated by Khaled Aljbailli and George Szirtes from the Arabic, a metaphor on tyranny which echoes one of the 12 themes Goethe wrote about in West-Eastern Divan.

Goethe's tyrant at that time was the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, who conquered the German poet’s home town of Weimar in Prussia in 1806.

Napoleon, an avid reader of Goethe's verse, met him twice and discussed literature. Goethe wrote in his diaries that Bonaparte asked him: "How old are you?" Goethe answered: "Sixty years," to which Bonaparte replied: "You are well preserved. You have written some tragedies.”

Barghouti says Goethe refused calls from German nationalists to hate Napoleon. He told them: "How could I hate the French culture, which I love?"

Goethe wrote West-Eastern Divan after reading the verses of the 14th-century Muslim poet Hafiz Shirazi, who came from Shiraz in modern-day Iran and was described by the German poet as his "twin soul”.

Hafiz's tyrant was the Mongol conqueror Timur, who built a massive empire in central Asia and Iran, and conquered Damascus, Baghdad and Moscow.

But Goethe was fascinated with Islam and the Quran even before he was inspired by Hafiz. At the age of 23 he wrote a poem in praise of the Prophet Muhammad: it is also said that he used to spend the Laylat al Qadr, the holiest night of Ramadan, undertaking prayer like a Muslim.

The shadow of Tahrir Square

Barghouti's poem, unlike those of Goethe and Hafiz, is set in the modern era and draws a picture of a pathetic tyrant, the sort commonplace in the news.

On 25 January 2011, Barghouti was present in Tahrir Square, Cairo during the uprising. He saw at firsthand the one-million strong protests that called for "the downfall of the regime" and saw the flow of the revolution's water.

"In Tahrir Square, I saw how poetry travels through time and space," he recalls. "I saw Egyptians recite the poem of [the Tunisian poet Abu al-Qasim] al-Shabi. 'If, one day, a people desires to live, then fate will answer their call.' Although al-Shabi died when he was 24 years old, his poetry is still alive."

Later Barghouti channelled his experience into The Obedience Of Water...

How many nights of art, close study, hesitation and sacrifice,

at little or great expense, do you need to invent

the simplest of gadgets?

All you need to invent a tyrant is a single

bend of the knee.

***

No, he's not a rhino, not a miracle,

in fact he may look like you. Or me.

Don't be fooled. Those are not his claws

they are perfectly normal nails like yours.

Nor are those hooves, no,

they are his size eight, possibly

size nine, shoes.

He's less heavy than you think. No, not a ton,

just the weight of an ordinary man,

say seventy or eighty kilos.

Is that his horn? No

it's his smug little, snub little nose and, yes,

he might catch a cold like you and I.

He might even bleed.

(...)

He regards even his tantrums as a sign of strength.

He would prefer us to be as water,

to see us stagnating at the bottom of the cup.

We must bow when he pours us out,

Not allowing a word to escape

and yet when we behaved like water as he intended

He raised his hands in mute appeal, astonished to be drowning.

Barghouti's last poetry collection Wake Up To Dream, was published in Arabic in 2018. It was received by Arab critics as an elegy to his late wife Radwa Ashour (1941-2014), an Egyptian novelist, whose work The Woman from Tantoura, is considered one of the best narratives written on the Palestinian exodus of 1948 and subsequent diaspora.

Ashour translated Barghouti's Midnight and Other Poems into English and was his soul companion.

"I love Wake Up To Dream - in everything I write, my aim is to produce a work of art," he says. "In this collection you could find my conclusion of producing a work of art."

Barghouti regards texts which aim to generate solidarity for the Palestinian cause as existing outside the realm of poetry, of being part of political activism, bloggers, and advertisements.

"The poet should mean what he says and says what he means and be accurate, and equip his poem with aesthetic elements,” he explains. “It does not matter if the topic is noble or not, the cause is big or small. The poem should also let the reader form a feeling, not to tell the reader how to feel.”

Barghouti dislikes the "military poem", he says, the one written by regime and opposition poets, which has a khaki color. True poems have multiple colours as diverse as that of human experience, he says.

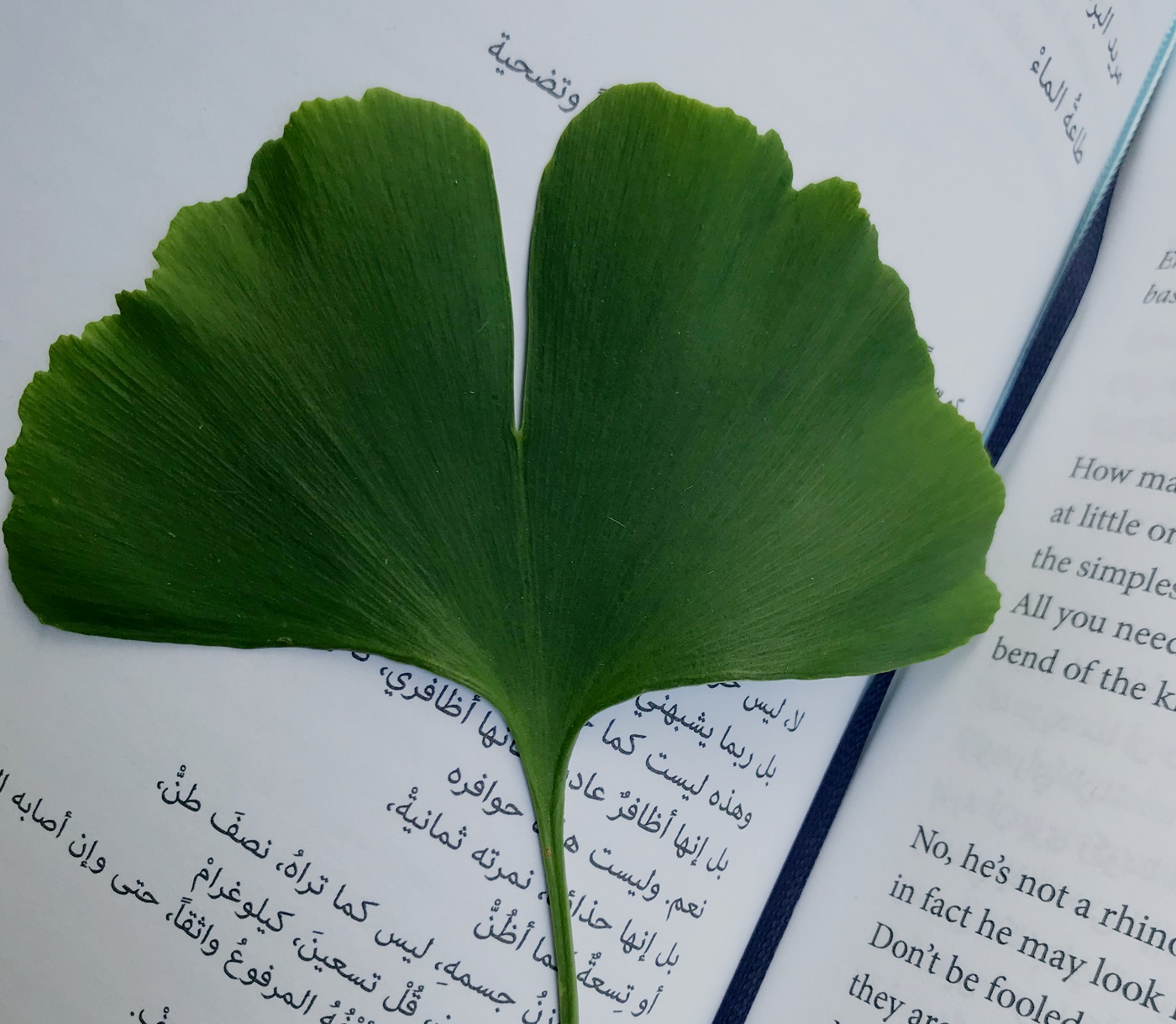

“Goethe was the most intriguing citizen in the world,” Barghouti says. He then pauses, leaves the table and walks to Russell Square to pick up a leaf from a gingko tree, the Japanese plant that inspired Goethe to write his famous love poem Gingko Biloba, in which the leaf replies to questions about whether it’s made of one part or two. Down the years, it echoes Barghouti's earlier comments about his reluctance to pledge allegiance:

To such questions I reply:

Do not my love songs say to you

- Should you ever wonder why

I sing, that I am one yet two?*

* Goethe's 'Gingko Biloba' excerpt translated by Anthea Bell

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].