From Sudan to Kaepernick, cartoonist calls for joint fight against oppression

On the face of it, the Sudanese protest movement and the American football star Colin Kaepernick, who kneeled during pre-match renditions of the US national anthem, do not have much in common.

Think again, says Khalid AlBaih.

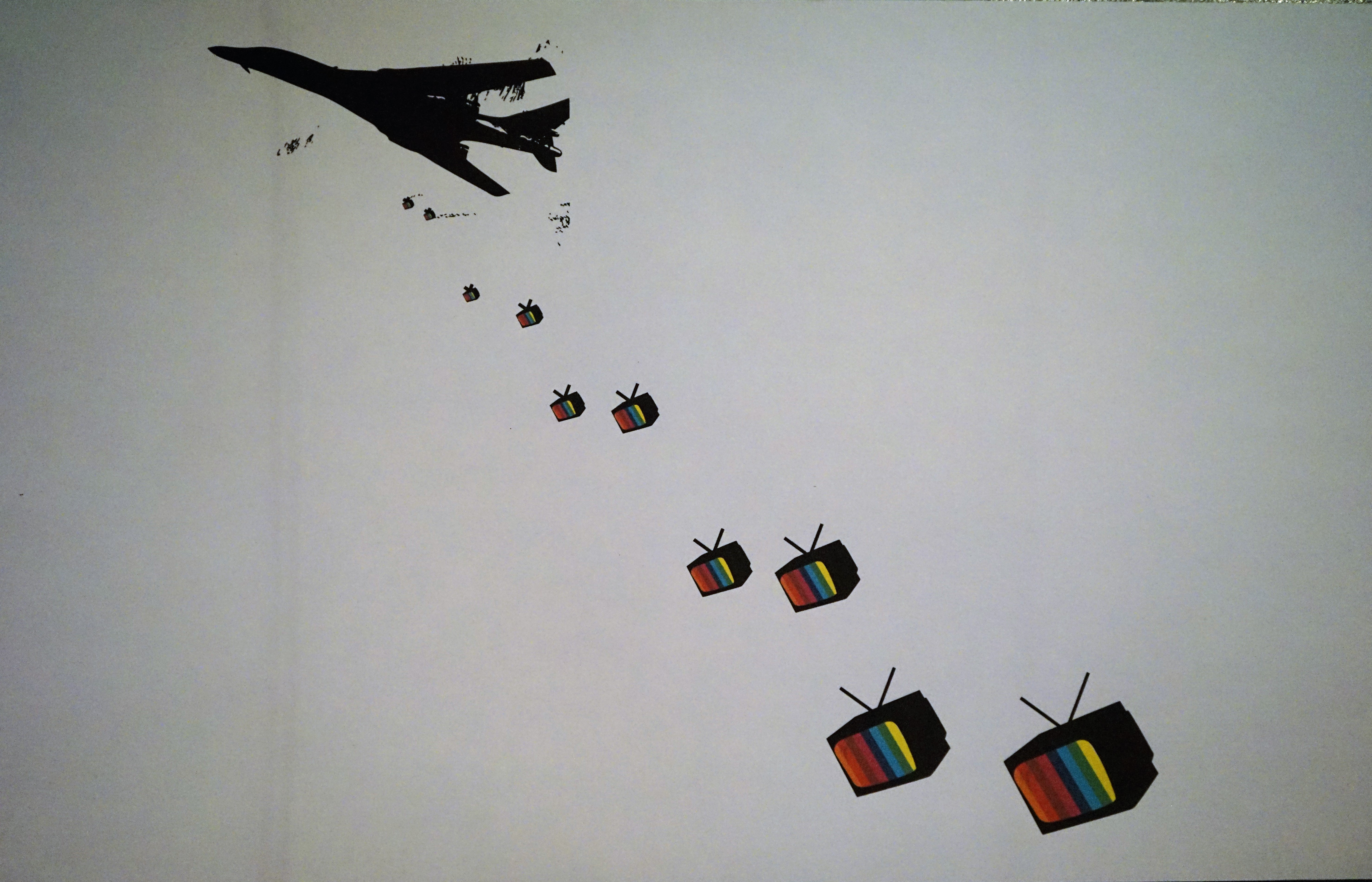

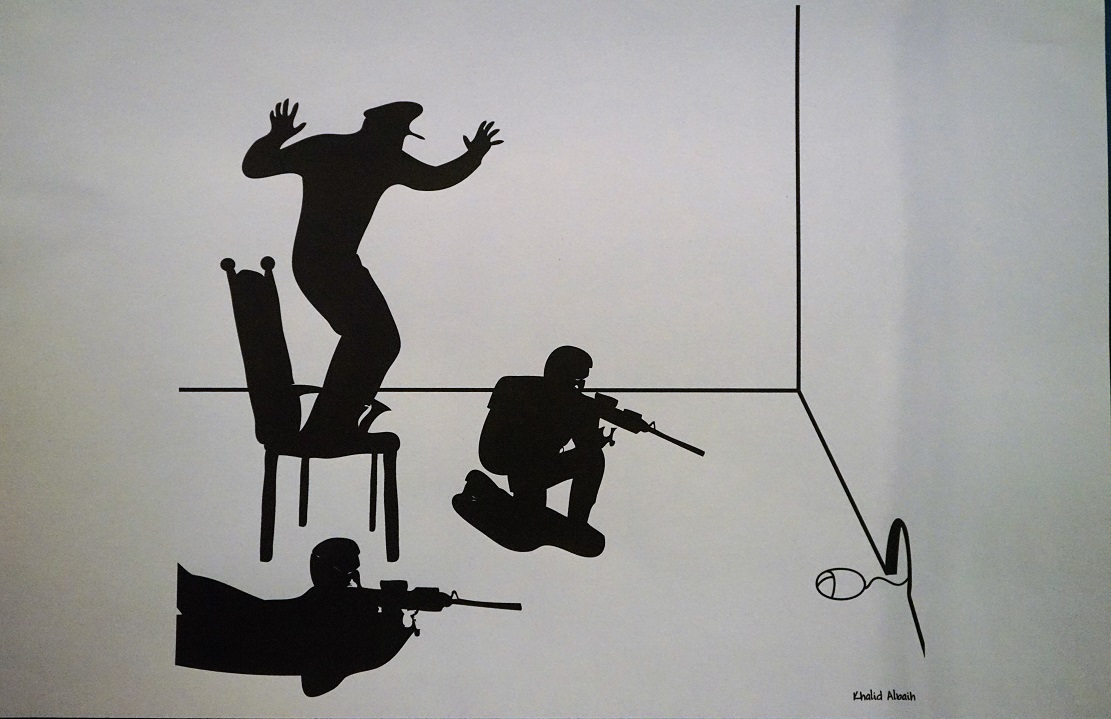

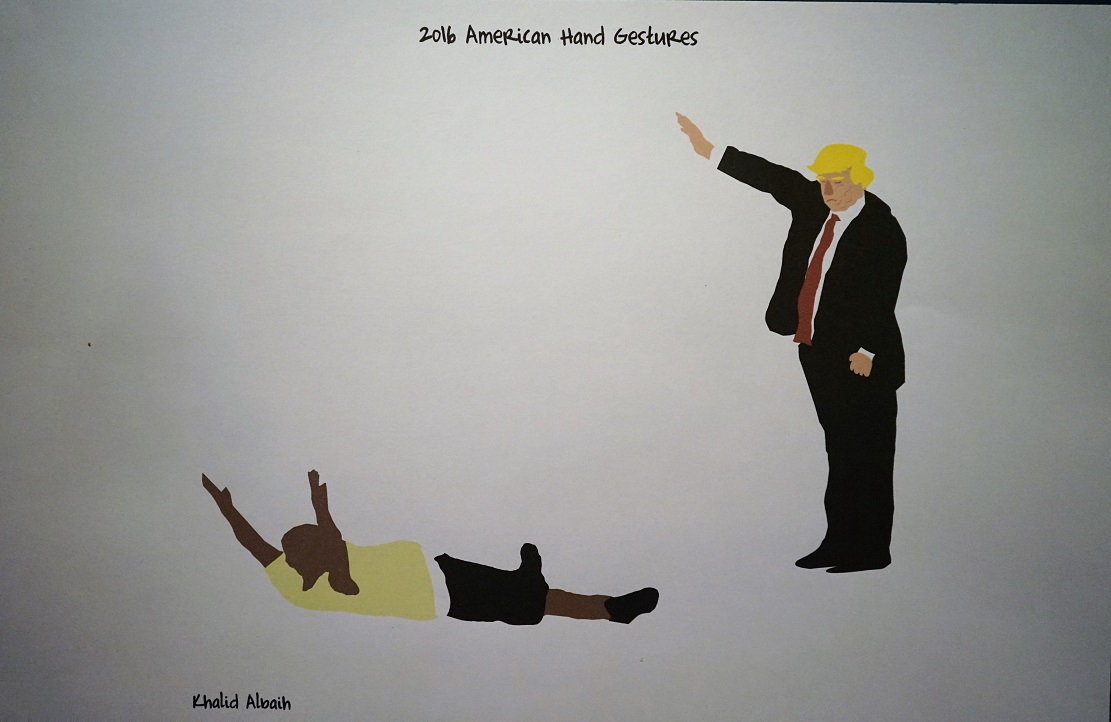

The Sudanese cartoonist's new exhibit opened in Manhattan this week, featuring his sharp takes on everything from his country's political crisis to the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback.

The way AlBaih tells it, Kaepernick and the crowds massed on Sudan's streets are both examples of the have-nots of the world - often discernible by their darker skin tone - challenging the mighty.

"Most of my work is saying that the struggle is one," AlBaih told Middle East Eye.

"We're all trying to fight the same things and one of the main reasons why revolutionaries, protesters and activists don't reach their goals is because we're not united; we think we're fighting different fights."

The victims of a 3 June massacre in Khartoum, #BlackLivesMatter activists fighting against police brutality, Palestinian refugees, and the Native Americans blocking a North Dakota oil pipeline — they all share the same battle, AlBaih says.

His show, Stumbling is not Falling, opened at ArtX in the Meatpacking District on Thursday with works that brazenly poke fun at everyone from President Donald Trump to Sudanese paramilitary chief Hemeti and the Gulf monarchs.

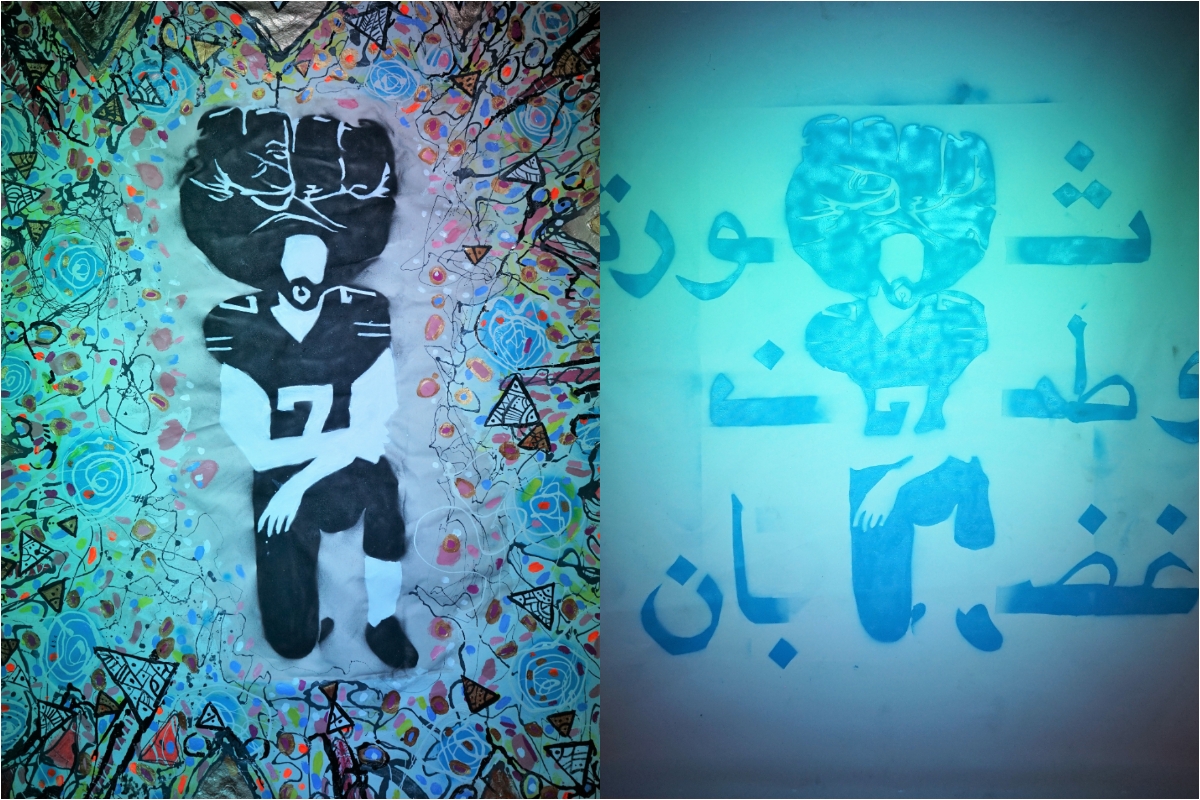

The show takes its name from a Malcolm X quote, and AlBaih's now-famous Kaepernick image takes centre stage.

The poster depicts the kneeling football player with his hair shaped into a "black power" clenched fist, which two African-American athletes raised on the podium at the 1968 Olympics in protest of injustices at home.

Renowned American filmmaker Spike Lee wore a T-shirt featuring the drawing, helping it go viral.

The exhibit is not all heavy politics though.

AlBaih, a self-confessed internet addict, mocks the modern man glued to his cell phone. In one cartoon, the blue Facebook "F" logo is shown as a syringe being jabbed into a drug addict's forearm.

The show runs until the end of July and charts the maturation of AlBaih's style, from earlier computer-produced silhouettes to his more recent use of spray cans and stencils, all influenced by the likes of Banksy and Palestinian cartoonist Naji al Ali.

AlBaih, 39, was born in Romania, where his father served as a Sudanese diplomat, and spent most of his life in Doha. A married father of three, he typically works in museums by day and draws at night, producing cartoons almost daily and sharing them online.

He rose to prominence with biting takes on the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings and has built up almost 30,000 followers on both Twitter and Instagram and about 87,000 on his Facebook page "Khartoon" - a play on the words cartoon and the Sudanese capital, Khartoum.

The bearded, bookish and bespectacled artist is both remarkably tall, standing 1.96m (6'-4"), and down to earth, often speaking with slangy chumminess.

Politics is in his blood - his dad was a diplomat and his uncle led a transitional Sudanese government in the 1980s.

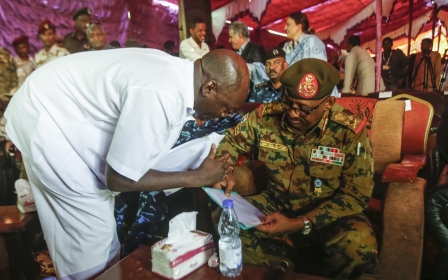

He went to Sudan and took part in some of the anti-government rallies in Khartoum late last year, which snowballed into a mass protest movement against then-president Omar al-Bashir.

Bashir was toppled in April, only to be replaced by a transitional military council.

But AlBaih said spending too much time in the country is unwise, and publishing satirical cartoons from there would be foolish. He currently lives in Copenhagen on a scheme for artists at risk of persecution. His next stop is Holland.

Freedom of expression

Satirists face risks everywhere, notes AlBaih. In May, more than 200 cartoonists signed a declaration that was sent to the UN's cultural agency, UNESCO, demanding safeguards for artistic freedoms.

The petition was signed four years after French cartoonists were gunned down in Paris at the satirical paper Charlie Hebdo.

Among the signatories are artists from far and wide, including India, Belgium, Spain, Algeria, the United States, Israel, Mexico, Turkey and Switzerland.

AlBaih highlighted restrictions on freedom of expression in North America as well.

He cited last month's decision to scrap political cartoons in the international edition of the New York Times after the publication of an antisemitic image, and the sacking of Canadian cartoonist Michael de Adder after he lampooned Trump.

"In the West, most people think these things can only happen in places like Sudan and Iran. But when it happens in the West, you don't get the same levels of outrage and I'm really wondering why," AlBaih told MEE.

"It's important people know that these things happen in the democracies they think they have."

This is another mainstay of AlBaih's thesis — countering Orientalist misconceptions, drubbing "white saviours" and neo-colonialists and letting his Western fans know: "I’m a victim of the last 100 years of your governments' actions."

'Hacking the system'

AlBaih communicates that message through his work.

His retort to Trump's 2018 slur that many Africans live in "shithole" countries came in cartoon form: the Republican Party's elephant emblem defecating on the president's head, with an onomatopoeic "tRRRUMP" to drive the message home.

This is where things gets tricky for AlBaih. He publishes online so he can remain independent of the Arab region's media outlets, which are typically aligned with governments and political movements.

Still, if his other target is decadent Western hypocrisy, then his popularity among upper-middle-class art buffs in Manhattan is a double-edged sword.

The same goes for accepting scholarships from George Soros, an investor and philanthropist, and from Colby College in Maine, one of America's whitest states.

'We're all revolutionaries, but we have to change things from within... I'm just hacking the system'

- Khalid AlBaih

Moreover, his work is on display at the Goethe-Institut Sudan, a German cultural centre in Khartoum itself.

Is he becoming what he loathes?

"It's a Catch-22," says AlBaih. "We're all revolutionaries, but we have to change things from within, otherwise we'll be in our own playground with nobody there. I'm just hacking the system."

AlBaih prides himself on sharing his cartoons online for free.

Reluctantly, he explains why he recently instructed lawyers to seek cash from the folks who print his Kaepernick icon on T-shirts. Living from "scholarship to scholarship" has left him "tired", he says.

Like the Sudanese protesters who cut a deal with the military last week, AlBaih adds that revolutionaries always have to face reality.

"I might just sell out and go work for Al Arabiya," he says, referring to a Saudi-owned media network.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].