In pictures: The village that's only for women

The idea behind Jinwar is that it is a safe space that can offer women freedom. The first houses – there are now 50 - were built in August 2017 from mud and wood. All food is homegrown: there’s also a bakery and a school. Men are allowed to visit if they are helping the village but cannot stay (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

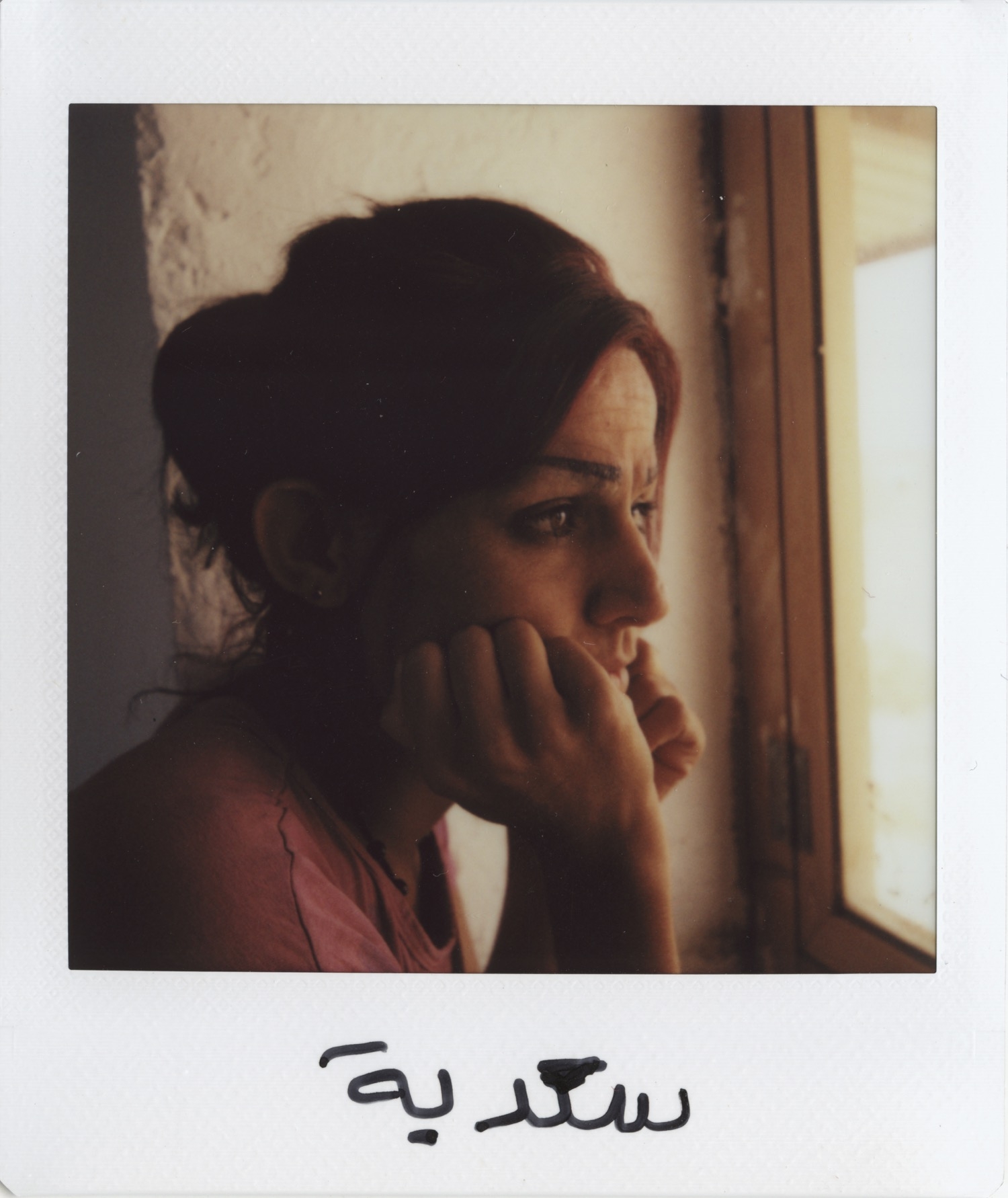

Sadiha, 37, is divorced and estranged from her family. For three years she did not see her eldest child, who her husband took with him to Turkey. “When I hugged him [my son] he didn't recognise me,” she says (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

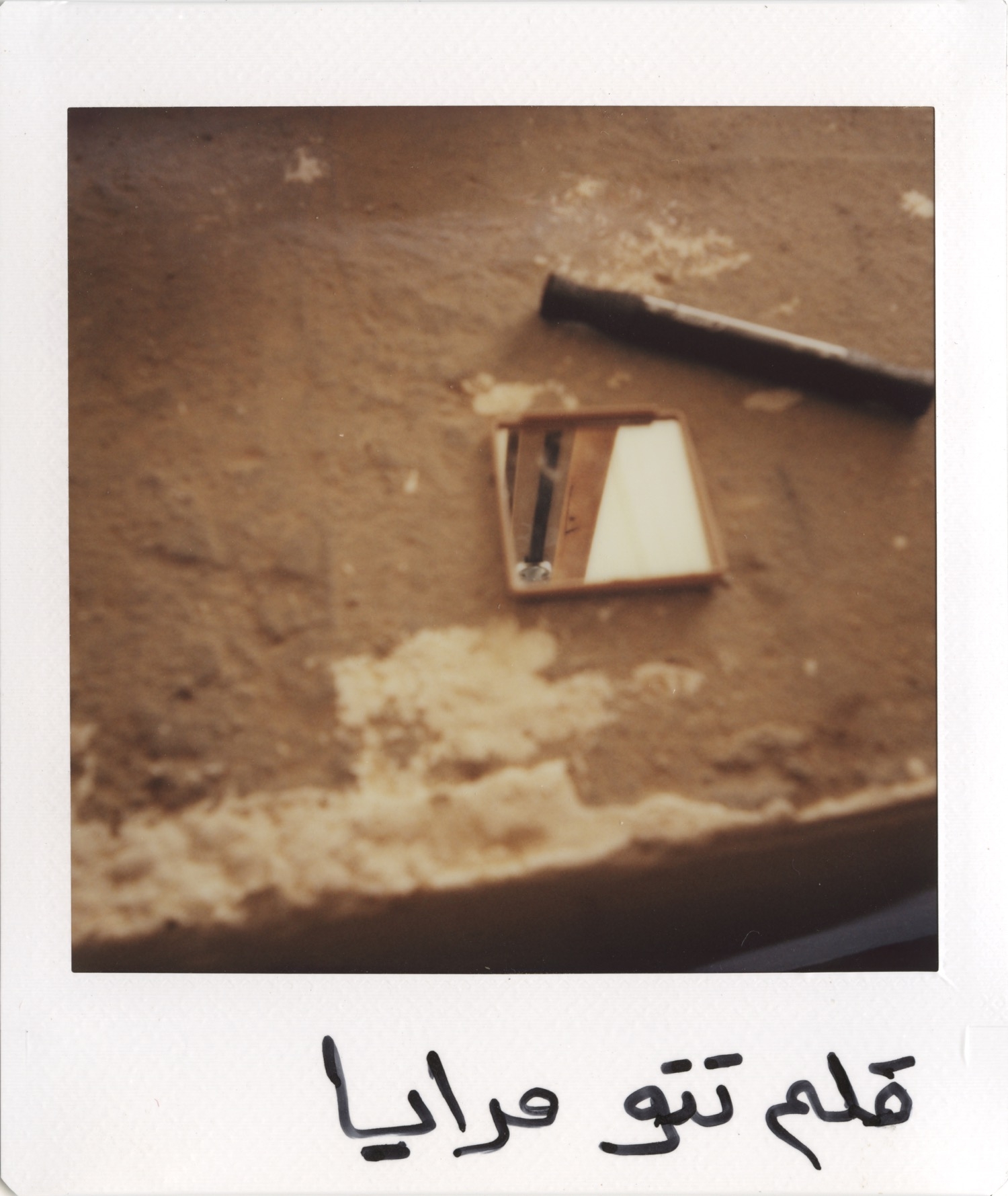

At 15, Sadiha had an operation to replace her eyebrows with tattoos – but didn’t have enough money to complete the procedure. Several times a day she uses straight brush strokes to replace her eyebrows (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

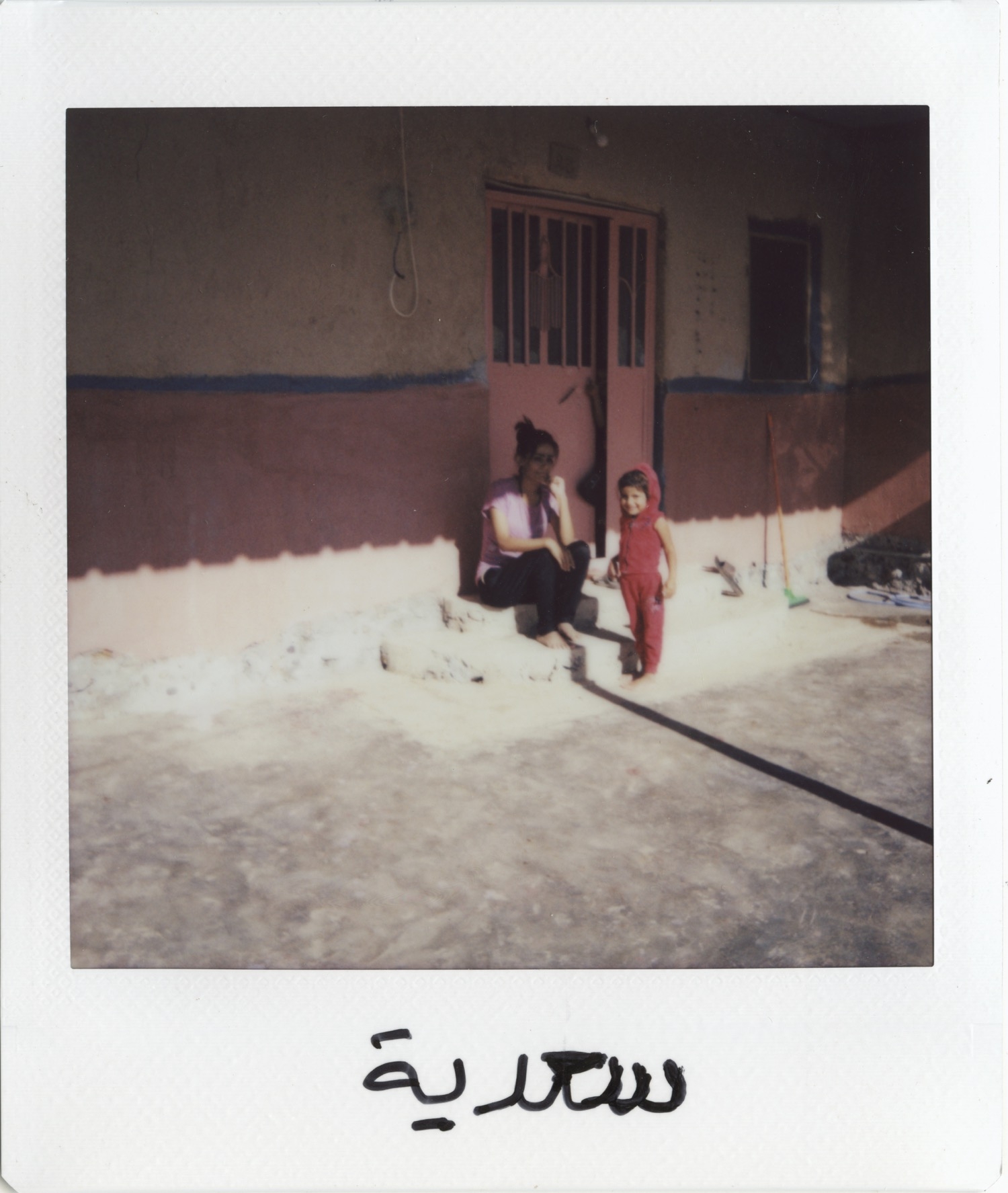

Before arriving in Jinwar, Sadiha, pictured with her daughter, begged and lived on the streets. “I prefer to forget my previous life,” she says. Since this image was taken, Sadiha has left the village to enlist with the YPJ, the female battalion of the Syrian-Kurdish forces. Sadiha's children are now cared for by her grandparents in Qamishli (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

Melka is a Yazidi and does not know how old she is: she lost her identity card when she fled the mountains of Sinjar. She is deaf and lives in Jinwar with her daughter Berivan, 12. “Here it is safer for two single women,” Melka says (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

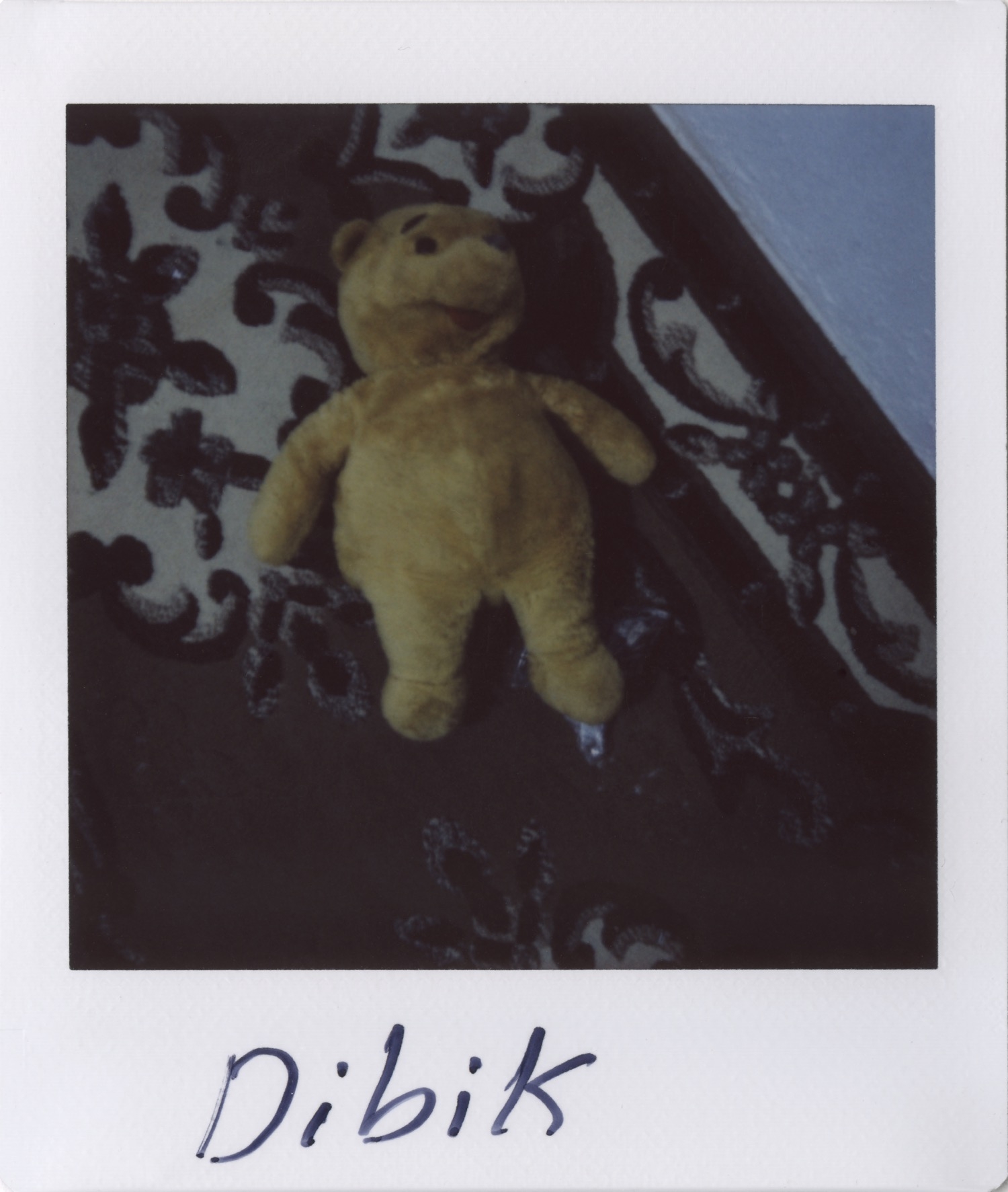

Berivan’s teddy bear: she has never met her father, who remarried and now lives in Germany (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

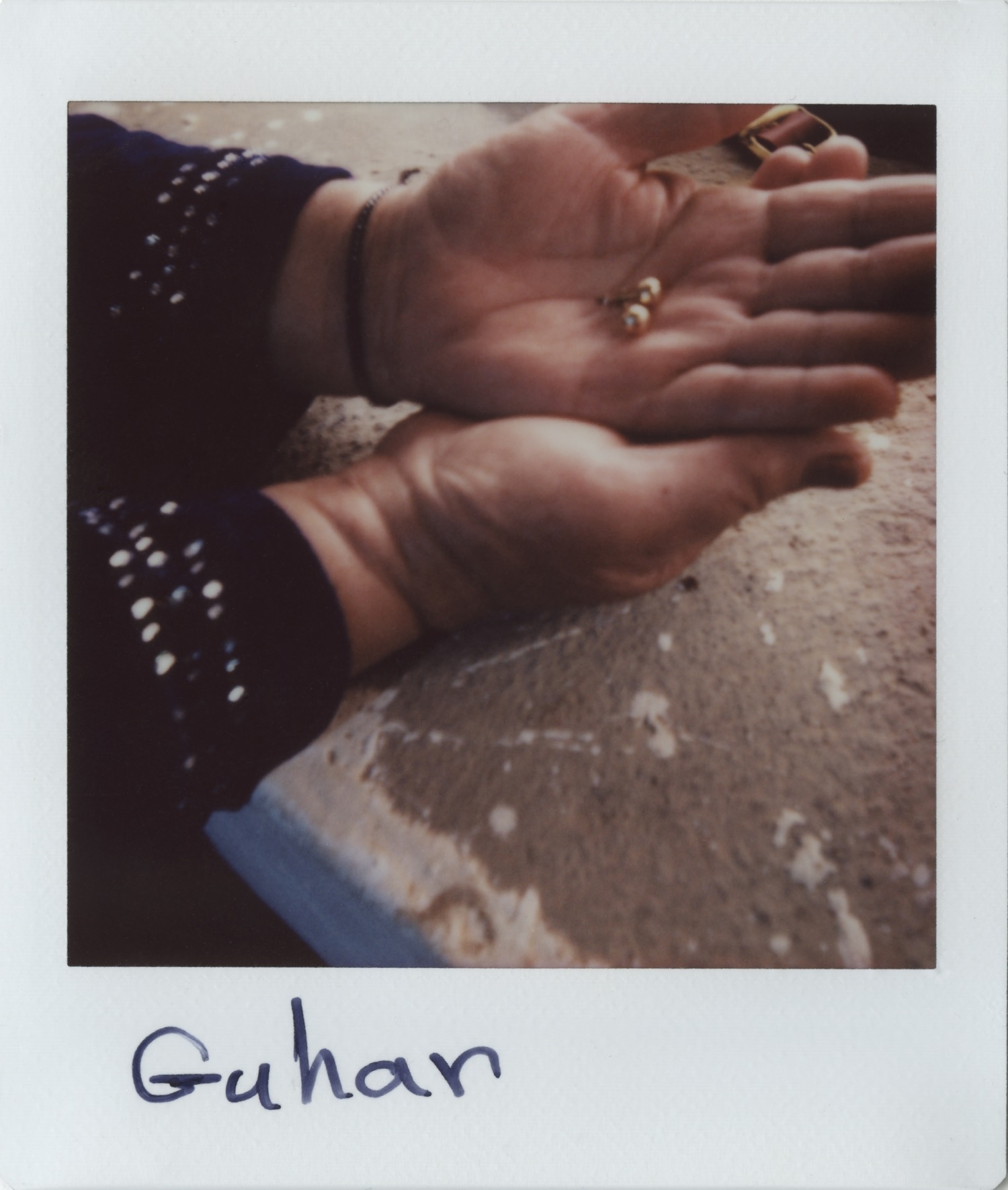

These earrings are Melka’s only reminder of her life on Sinjar: she had another pair but they were stolen by a neighbour before she arrived in Jinwar (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

Nesrin, who is 16, is the eldest of seven sisters. Her dream is to play the violin. “The sound of the violin expresses my pain,” she says. "This is how I would like to express myself, reaching those who listen to me.” Her pain, she says, is because of the death of her father, who was killed by a mine in Kobane in 2015 (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

Nesrin with her six sisters: Fatima, Nesrin’s mother, took her away from Kobane when an uncle wanted her daughter to marry a cousin (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

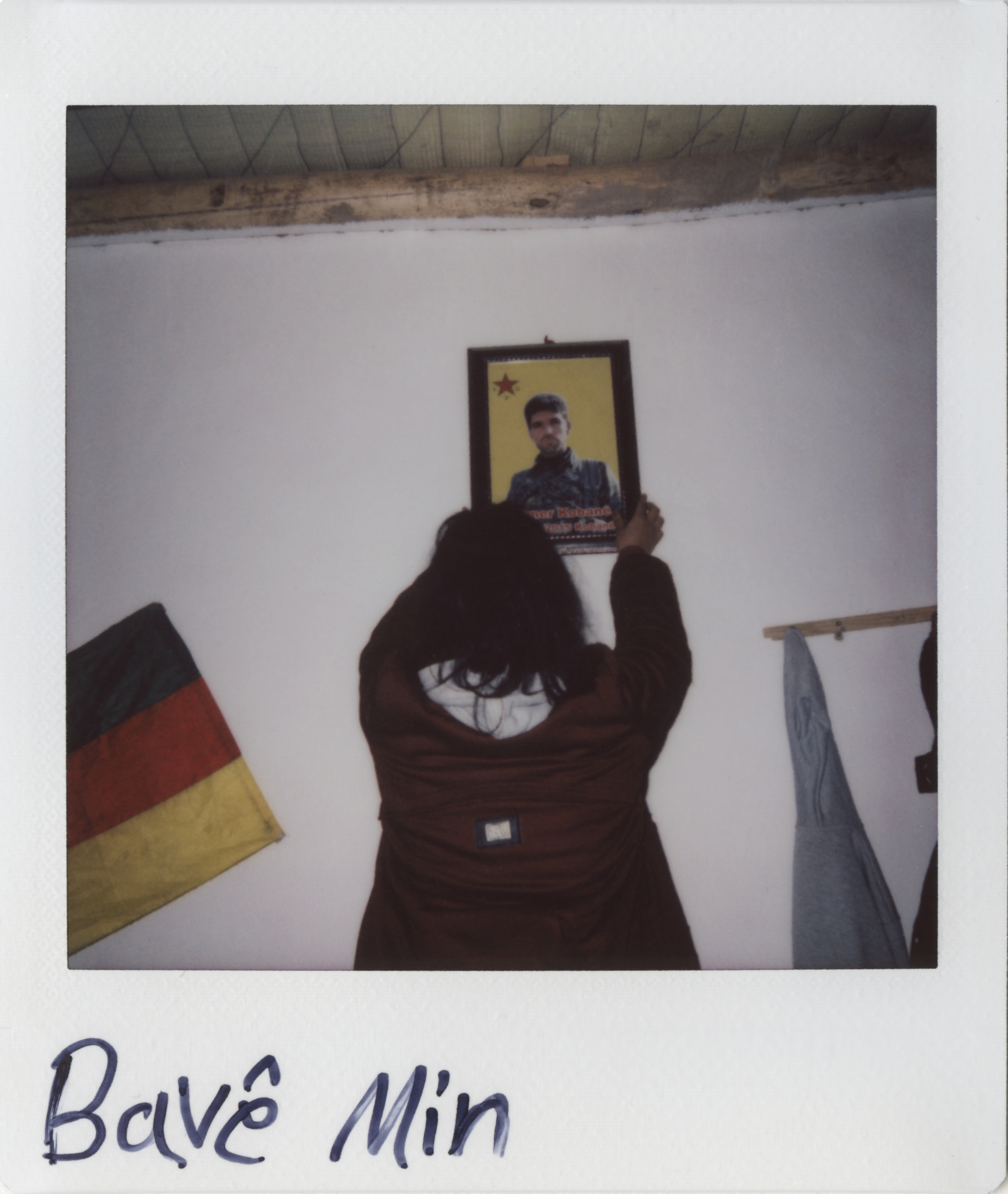

Nesrin adjusts a photo she took of her late father. His family has opposed Nesrin playing the violin as they say it is not suitable for women (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

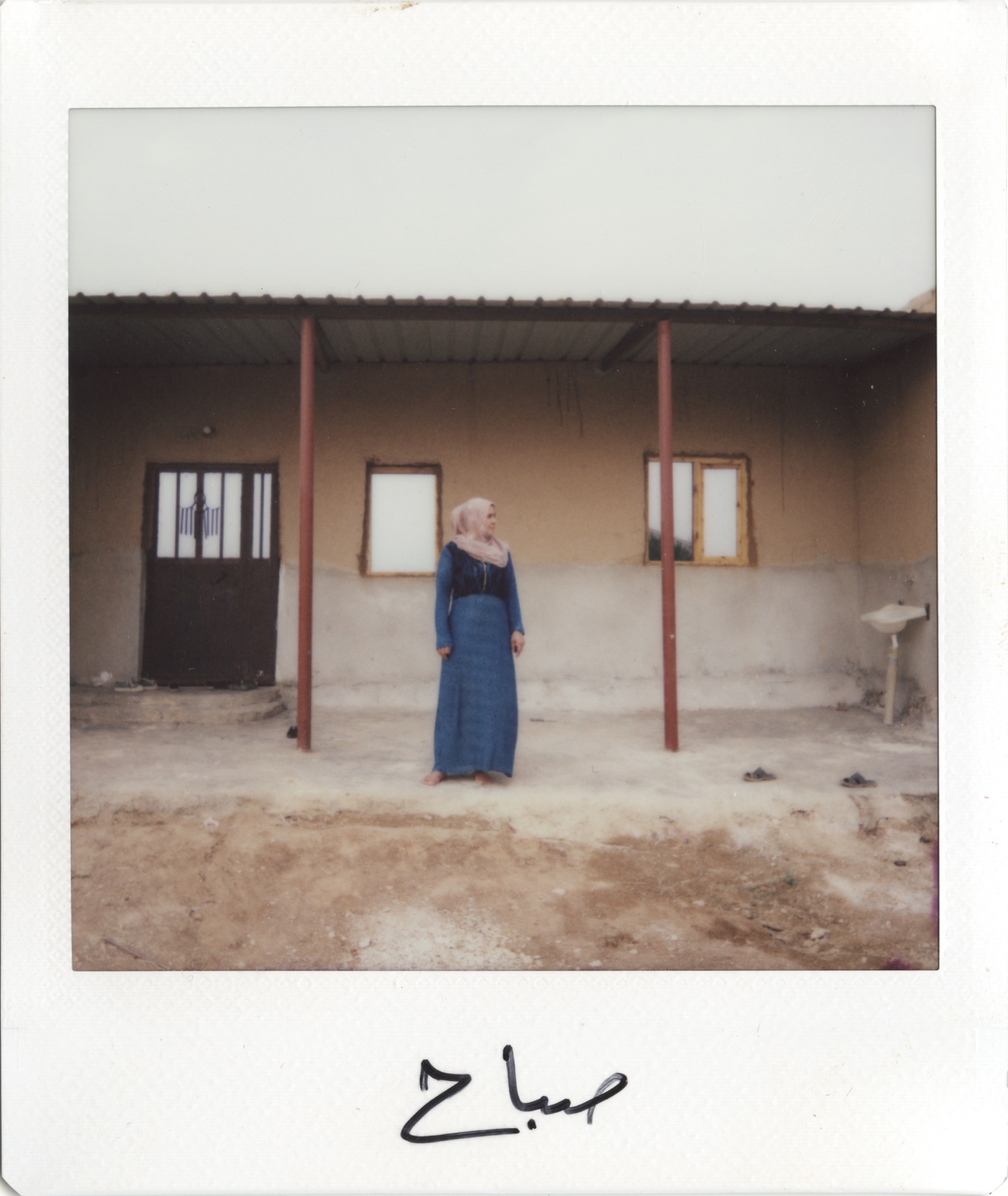

Sabah, 40, lived for three years under Islamic State in Deir Ezzor. The pain of the past is represented by a photo of her son Sultan, who died in Raqqa at the age of 19. "Whoever has left Syria says that in Europe everything is nice and the children can go to school,” she says (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

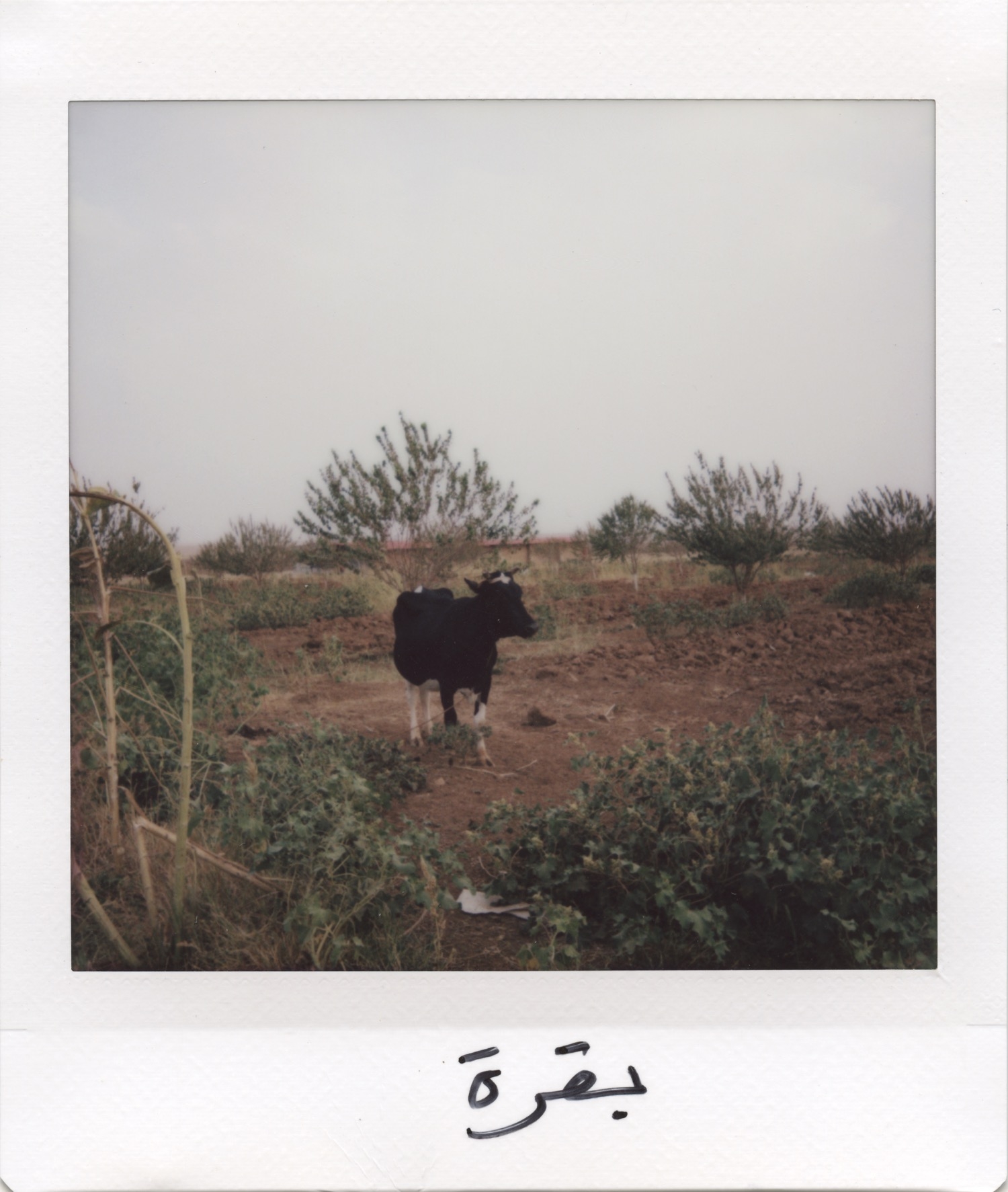

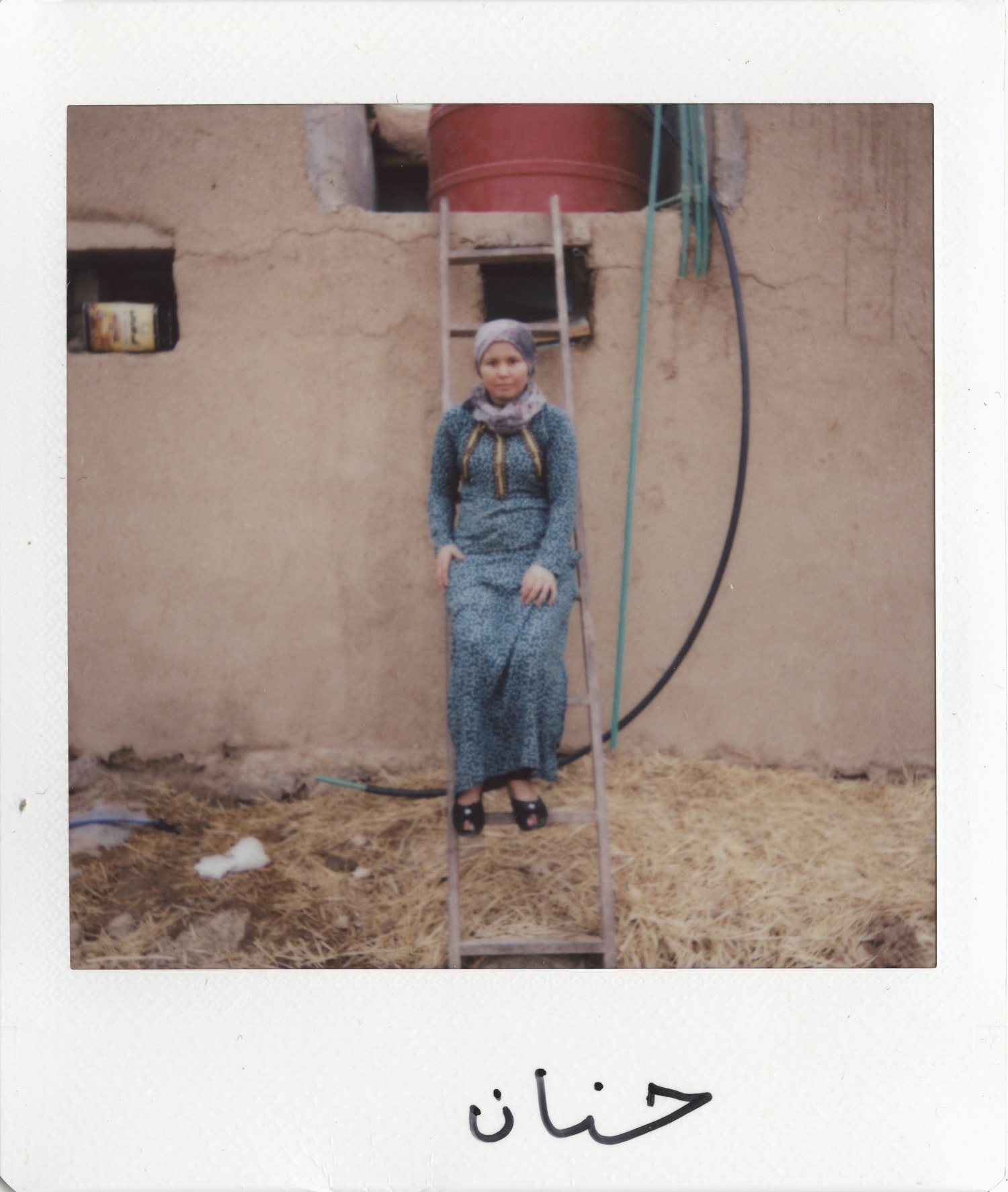

When Sabah, her daughter Hanan, 22, and the rest of the family fled Deir Ezzor, they took with them their fridge, cows, pigeons and chickens. The women lived elsewhere before settling in Jinwar, where they earn a living by working in a bakery (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

Hanan's husband returned with their two children to Deir Ezzor: she has since discovered that he has remarried. The same happened to Sabah. Hanan says: “I miss my children but what can I do?” (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

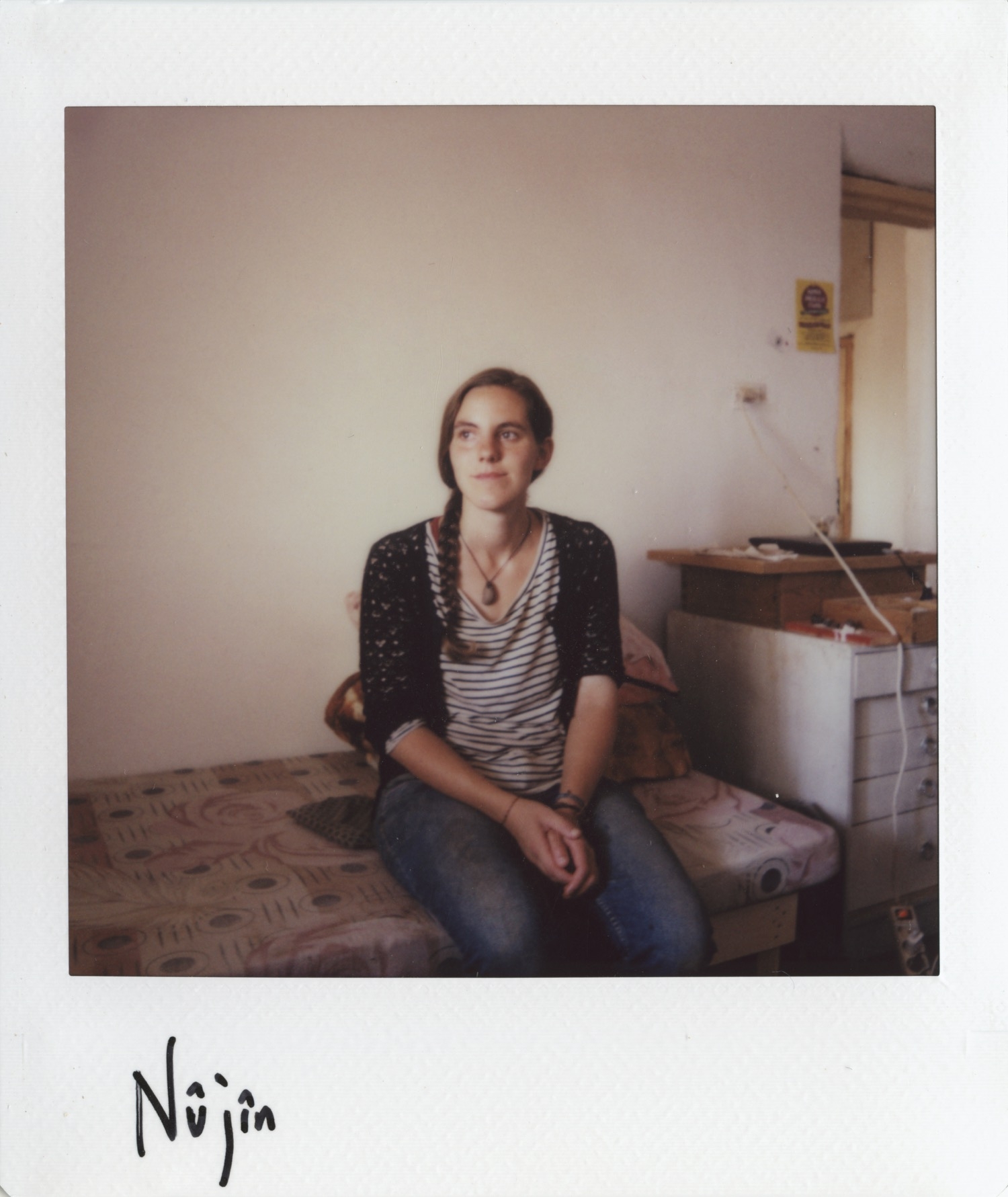

Nujin, 28, from Dortmund in Germany, arrived in the region three years ago. She is one of several foreign women who have helped organise the community, including welcoming committees (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

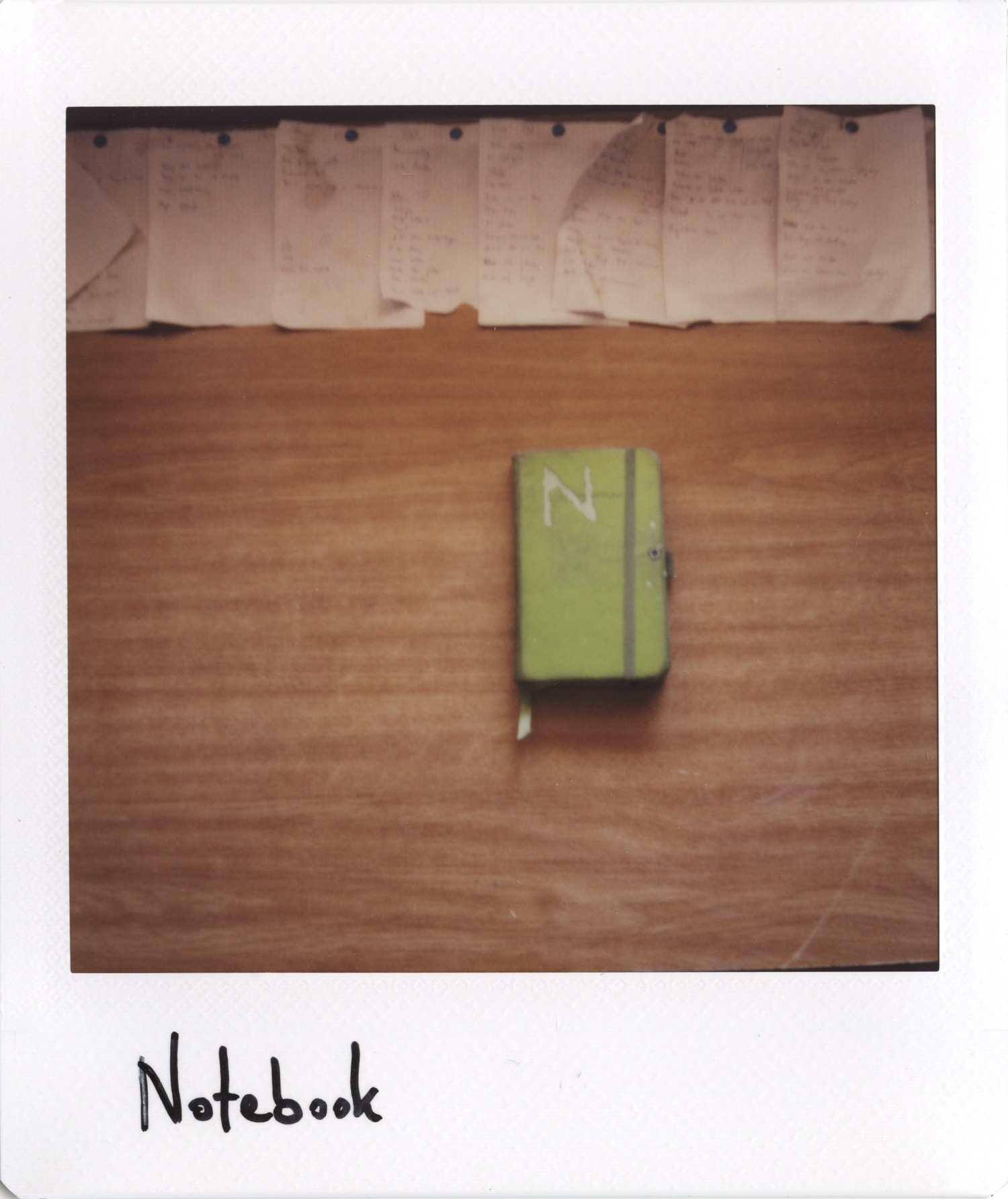

Among the possessions Nujin brought with her is her diary. She writes in it at her desk in the evening, ignoring the bites from gnats. “Living in Jinwar is not a holiday, a flight of fancy or a sabbatical retreat,” she says (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

While Nujin was helping build Jinwar, she came across these three bullets. She kept them, she says, because “sometimes I forget the war has also crossed this place” (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

Badra lives with her seven children in Jinwar: in each of them she recognises her husband, who was killed fighting Islamic State in Shaddadi. “I’m still thin ,despite 14 pregnancies,” she laughs. “If he had not been killed, we would have continued” (Linda Dorigo/MEE).

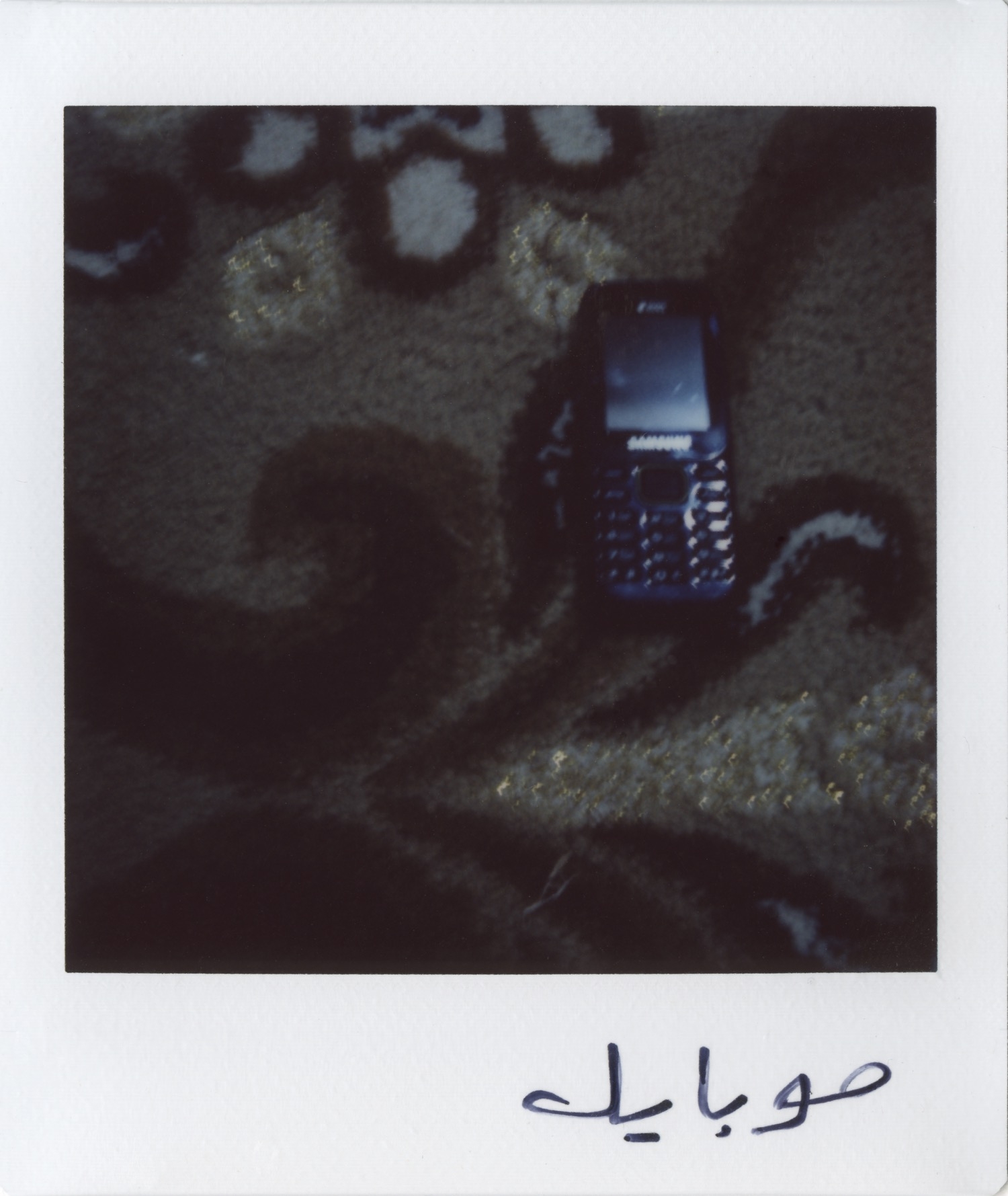

Badra hopes that her children will find their own way in life. “For me, I have no wishes,” she says. “It’s enough to have kept my husband’s cell phone, so every time it rings he’s still with me” (MEE/Linda Dorigo).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].