Dangerous precedent: East Jerusalem neighbourhood faces mass house demolitions

Rising to nine floors and able to accommodate 40 apartments, Mohammed Abu Tair’s almost-built building in Wadi Hummus should be one of the prides of his life.

Once completed, it would have become home to dozens of Palestinian families who are increasingly priced out of Jerusalem, which is about 5km away.

Instead, it’s slated for demolition.

Sitting in the occupied West Bank’s Area B, under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority (PA), the development was built with all the necessary PA permits.

The problem is that it lies close to Israel’s notorious separation barrier, which cuts the West Bank from Jerusalem, and Israeli authorities have ordered Abu Tair’s building and 10 others to be torn down.

“Where should we go?” Abu Tair despairs.

On Thursday, the deadline for the buildings’ owners to demolish their houses themselves passed, with Israeli bulldozers expected to roll in any day now after soldiers inspected the site.

The demolitions would set a dangerous precedent.

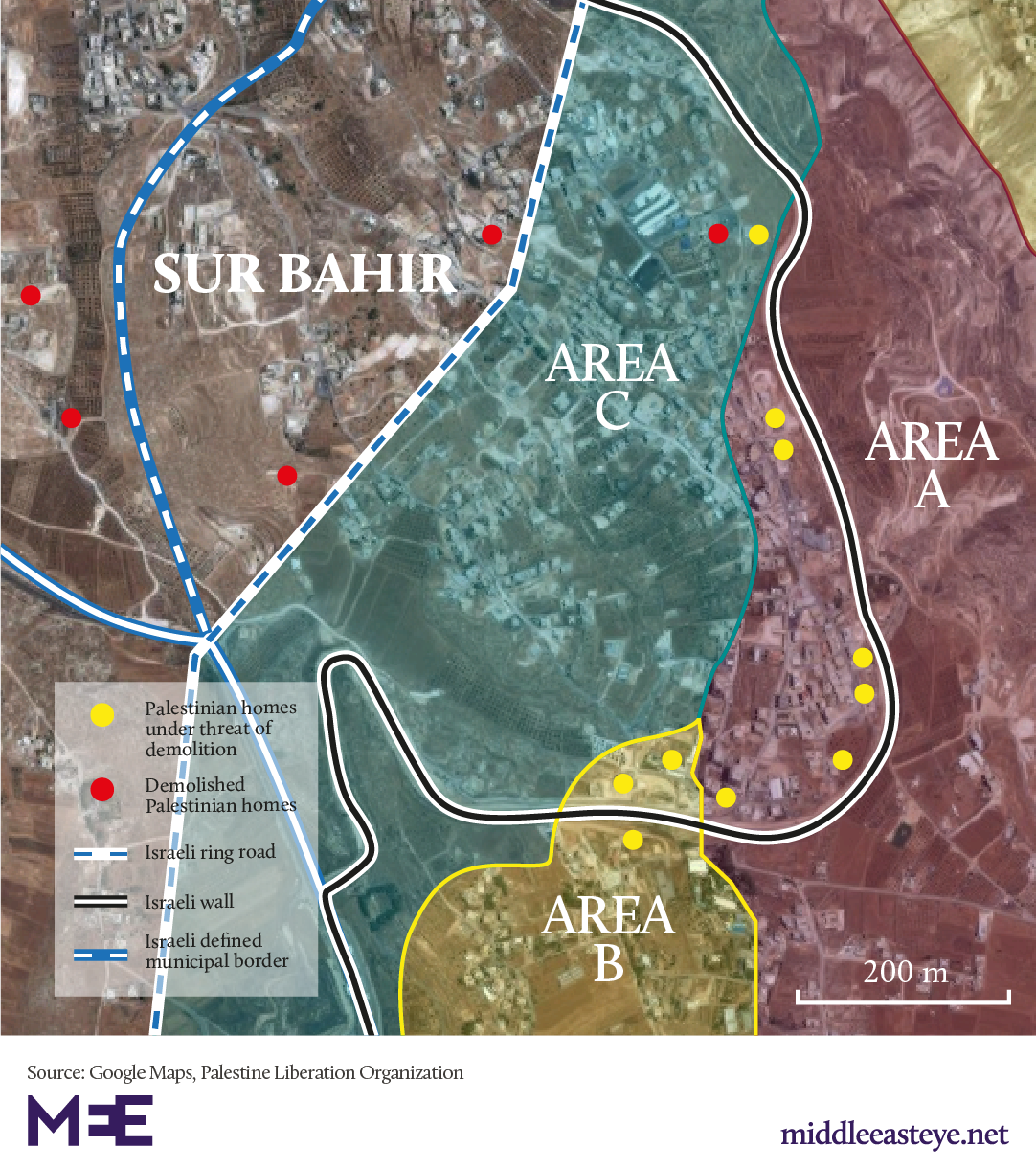

Wadi Hummus, a neighbourhood of Sur Bahir village, has a peculiar administrative situation, in that it lies across Areas A, B and C of the West Bank – the first two of which are administered by the PA, the latter by Israel.

And despite being part of the West Bank, it lies on the Jerusalem side of Israel’s separation barrier, meaning its inhabitants have far easier access to the city than Palestinians across the wall, and effectively live under direct Israeli control.

According to the Oslo Accords, Israel should have no say on whether or not homes should be built in Areas A and B. However, a 2011 Israeli military decision has decreed that Israel can now demolish buildings in PA-administered areas. Wadi Hummus would be the first.

Room to live

Palestinians in Jerusalem find it near impossible to obtain building permits from the Israeli authorities who have occupied the city’s eastern neighbourhoods since 1967.

So for some like Ghaleb Abu Hadwan, 63, Wadi Hummus was a perfect place to expand to.

As his family grew, Abu Hadwan, his children and grandchildren felt suffocated in the tiny 15X7 metre area of Shuafat refugee camp they were allotted to live in, after being expelled from the Old City of Jerusalem in 1967.

So they looked a little south, to Wadi Hummus, where PA building permits are far easier to come by.

'Even if we fly to the moon, they will follow us and deport us'

- Ghaleb Abu Hadwan, resident

But in 2003, at the height of the Second Intifada, Israel began erecting its separation barrier right next to Abu Hadwan’s land.

In 2011, Israel banned any construction 100-300 metres from both sides of the barrier on the pretext of creating a security buffer zone.

In the Sur Bahir area of Wadi Hummus, 200 buildings lie in this buffer zone, half of them built before the 2011 decision, according to the United Nations.

Now Abu Hadwan’s home is at risk. “Even if we fly to the moon, they will follow us and deport us,” he said, pointing at the sky.

Hamadeh Hamadeh, head of the Sur Bahir-Wadi Hummus Services Council, said the Israeli army had made minimal attempt to enforce the building restrictions since 2011.

“When the army saw new construction, the owners were only asked about their building permits,” he told Middle East Eye.

That’s a complaint echoed by Alaa Hamid Amira, 39, whose house is also threatened.

“While I was building, the army would stop by all the time and look at how it was developing. They would enter on the pretence of checking the labourers had the right paperwork and they never said it was illegal,” he told MEE.

“That’s why I was surprised when I found a demolition notice stuck to my door in 2017.”

Amira said he spent 400,000 shekels ($110,000) building his home. “It was the fruit of 20 years of saving. Now they will demolish, that will disappear and I will be left with zero.”

Court battle

On 11 June, with the Supreme Court confirming the demolitions must go ahead, Israel ordered the Palestinians of Wadi Hummus to take down their houses within 30 days.

In an effort to stay the bulldozers and stop 17 Palestinians, including nine children, from being made homeless, an appeal was filed to the Israeli High Court to ask for a 60-day extension.

On Friday that was denied, though the residents were offered one more day to carry out the demolitions themselves before the Israeli authorities tear the buildings down and bill the Palestinians for the labour.

The residents have been pursuing any means possible to stop the demolitions.

At one stage in the two-year legal proceedings, the judges asked the Palestinians to submit their proposals for an alternative security measure that would ensure the Israeli barrier’s security.

The residents then collected enough money to hire an Israeli security expert, who visited the site and drew up alternative recommendations.

Among the suggestions given by the expert were increasing the size of the wire on the separation barrier, placing more cameras in the area and adding modern electronic monitoring systems. The judges refused the proposal.

“In court, they refused any alternative suggestions for security instead of demolition, like keeping all windows facing the barrier closed,” lawyer Haitham al-Khatib, who represents the residents, told MEE.

“It is clear that they are only interested in carrying out the demolitions as soon as they can.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].