Uighur refugees face deportation to China from Turkey

Turkey is threatening to deport Uighur refugees back to China, where they could face imprisonment, after Turkish officials rejected their applications for asylum and long-term residency.

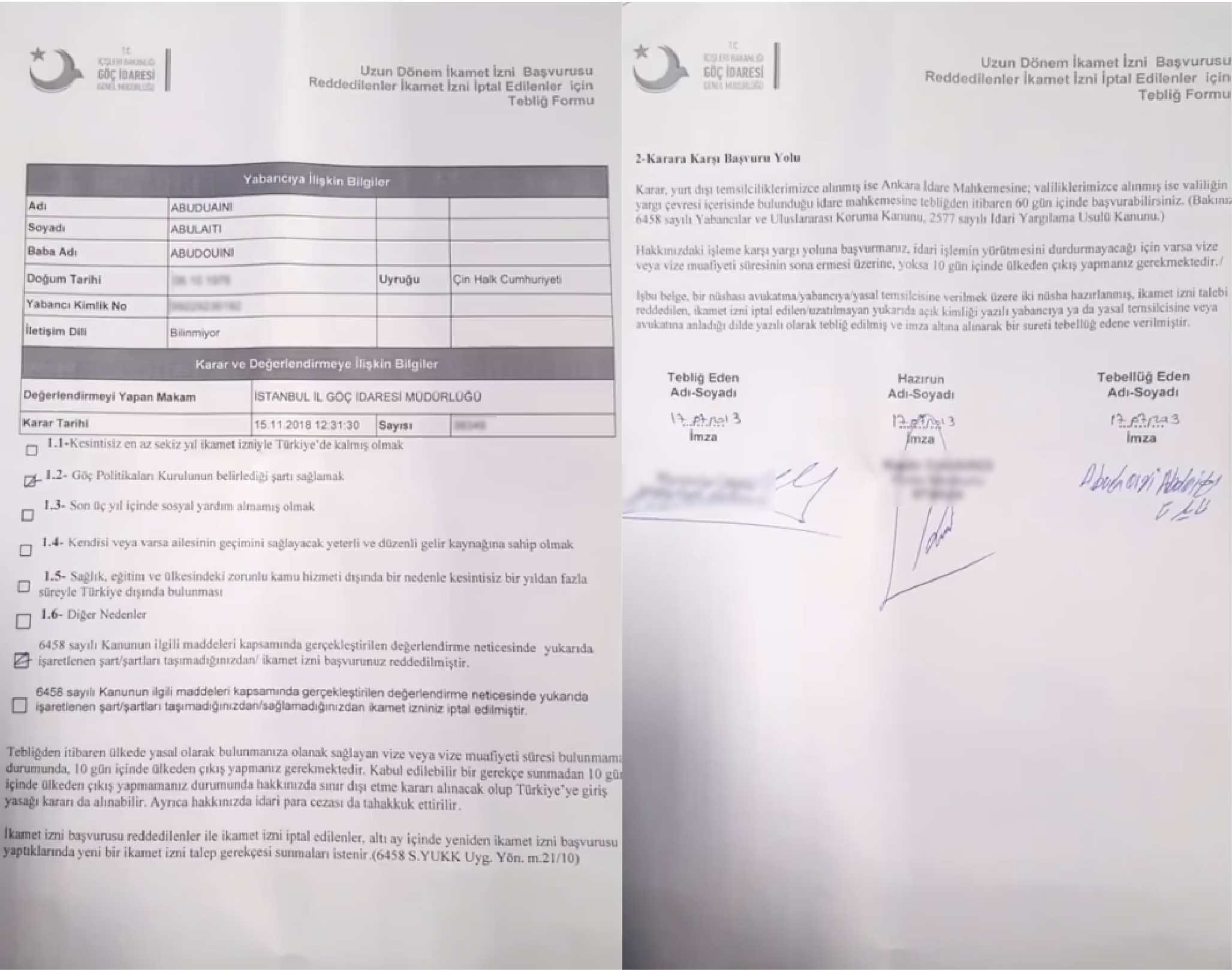

Documents obtained by Middle East Eye showed that Turkey has rejected several applications for Uighurs hoping to obtain long-term residency inside the country.

Immigration officials did not specify why they had rejected the Uighurs' applications, but said they would be deported within 10 days.

Who are the Uighurs and why is China targeting them?

+ Show - HideAccording to multiple reports, more than one million Uighurs, a Muslim-majority Turkic people, are currently being held in internment camps across Xinjiang in western China (or occupied East Turkestan as many Uighurs refer to the region).

Human Rights Watch said in September 2018 that up to 13 million Muslims in Xinjiang have been subjected to “forced political indoctrination, collective punishment, restrictions on movement and communications, heightened religious restrictions, and mass surveillance in violation of international human rights law”.

The Uighurs have have been particularly targeted since Communist party leader Chen Quanguo became Xinjiang’s party secretary in 2016. Under his leadership, a massive surveillance infrastructure was unrolled across the region designed to monitor and control the Muslim community.

Uighurs and ethnic Kazakhs have been routinely rounded up for practising their Islamic faith, including praying, observing Halal, or wearing clothes synonymous with being Muslim.

The Chinese government has even labelled Islam an “ideological illness” and has destroyed some mosques in the region. In the camps, detainees are forced to learn Chinese Mandarin, praise the ruling Chinese Communist Party and face recurrent psychological and physical abuse.

Uighur activists say that entire families have disappeared into the camps, or have been executed.

China has repeatedly denied allegations that it is persecuting the minority group, instead describing the camps as “vocational training centres” designed to counter religious extremism.

It also calls concerns raised by Uighur community members, human rights groups and others “unjustified” and an “interference in China’s internal affairs”.

Some refugees had applied for their long-term residency in 2017 and told about the outcome a month ago. The rejection papers state that the refugees could reapply but only from their country of origin.

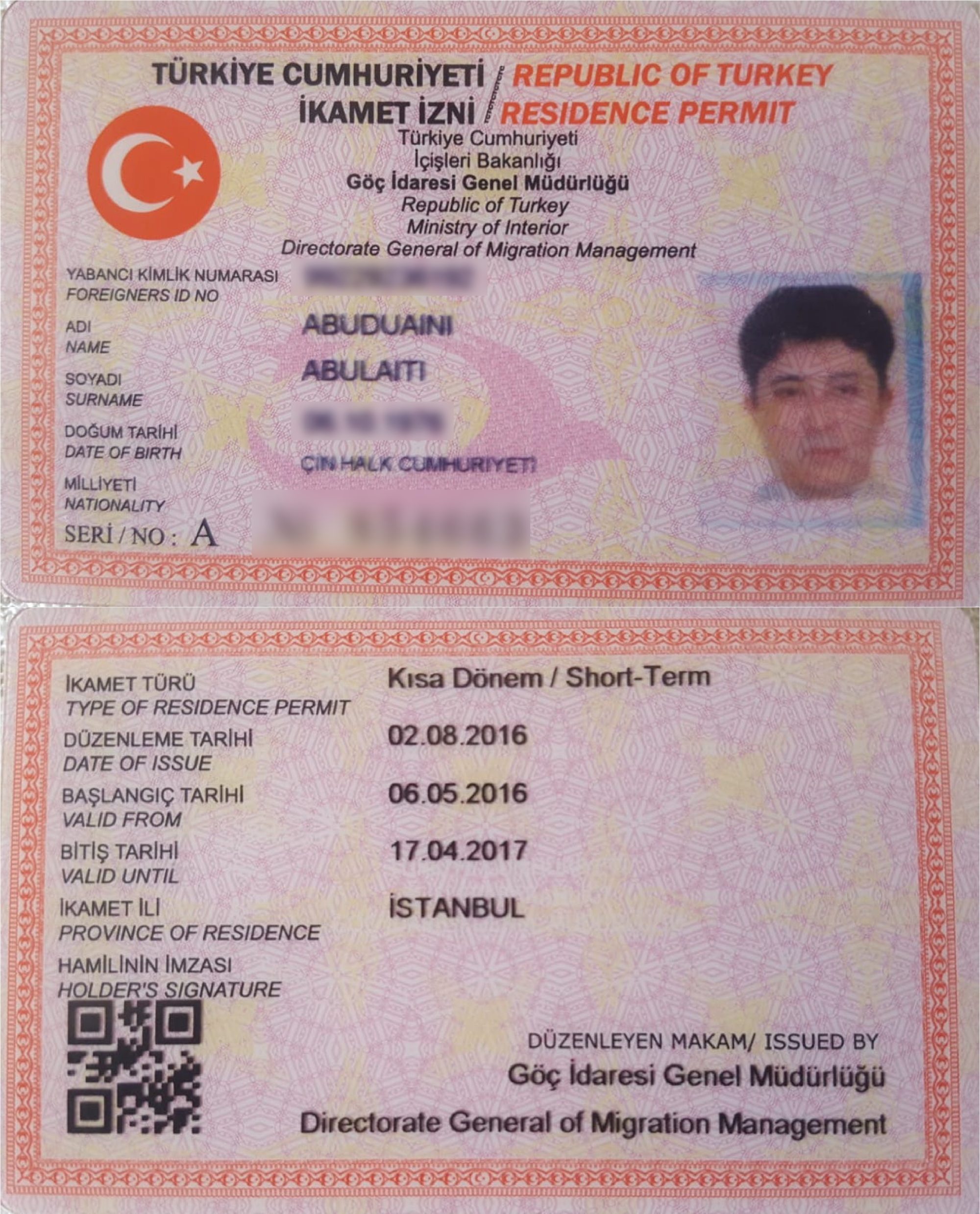

Abuduaini Abulaiti, a Uighur refugee who has lived in Turkey since 2012, reapplied for long-term residency in 2017. He said this request was rejected a week ago, in a letter that stated he had 10 days to leave the country.

"When the letter arrived, I was very very shocked that this had happened," Abulaiti told Middle East Eye from his home in Istanbul.

Having gone to Turkey via Malaysia to attend his fathers funeral and escape persecution in China, Abulaiti explained how three of his brothers had gone missing in the last two years.

"I had to go to Turkey through Malaysia because taking a direct flight to the country would have caused suspicion from Chinese authorities," said Abulaiti.

"We know that two of my brothers are in the re-education camps [in China] and alive after someone told us, but one of them is still missing, and we don't know whether he is dead or alive.

"I don't know what will happen to me if I go back. I may face the same fate as my brothers."

Another Uighur refugee based in Britain is desperately trying to get his wife and five children back from Istanbul. His family was handed deportation papers by the Turkish government after their application for long-term residency was denied.

Fearing retribution from Turkey's immigration police, the Uighur wished to remain anonymous, as his family lives in Turkey without legal documentation.

"We have traded in Turkey for several years and contribute to the society there too, so when the rejection for our long-term residency came in May 2018, we were very surprised," the refugee told MEE.

"The Turkish government gave an extension to our residency, but that ran out in May 2019. She [my wife] then received a paper saying they will be deported in ten days and she is now living with my children in the shadows, where they hide from the police to avoid being taken back to China."

Turkey's Interior Ministry did not respond to repeated requests for comment at the time of writing.

Historical safe haven

Turkey has historically been a safe haven for Uighurs, a Turkic minority, fleeing religious persecution in China since the 1960s, with thousands living in cities across the country.

While Ankara has criticised Beijing over its treatment of Uighurs, Turkey was not among 22 countries which called for an investigation into abuses inside China at the United Nations Human Rights Council earlier this month.

'I don't know what will happen to me if I go back. I may face the same fate as my brothers'

- Abuduaini Abulaiti, Uighur refugee

Earlier this year, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said he was "deeply concerned" by China's "persecution of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang".

Cavusoglu, however, did not comment on the re-education camps that have imprisoned an estimated one million Uighurs and other Muslims.

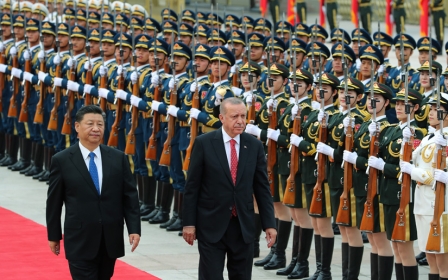

Critics, however, claim that Turkey's support for the Uighur minority was watered down after Ankara sought out better trade relations with Beijing.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan did not address the issue in public remarks during a visit to Beijing last month.

A Turkish presidential spokesperson said Erdogan and Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping discussed the Uighurs in private talks.

Erdogan also accepted an invitation to send a delegation to the Xinjiang region to observe how Uighurs are being treated, the spokesperson said.

Abduweli Ayup, a human rights defender based in Turkey, has been helping Uighurs facing imminent deportation. He told MEE that many Uighurs had waited years before receiving their deportation papers.

Ayup said that the "reasons for why their application was denied is unknown but will mean they could face imprisonment if sent back to China".

The human rights defender noted: "Turkey says that they can re-apply for long-term residency, but only from their country of origin, meaning they would have to physically go back to China, where there is an ongoing crackdown against Uighurs."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].