How the Arab state turned into a killing machine

The number of victims of repression in the Arab world exceeds that of all foreign conflicts that modern Arab states have fought since their inception around a century ago.

A quick inventory of the victims of Arab regimes that came to power post-independence reveals the extent of violence that the Arab state has inflicted on its people, transforming it from a bureaucratic apparatus serving its population to a killing machine, committing violent acts under the guise of legitimacy.

From Syria to Sudan

In Syria alone, in less than a decade, more than half a million people have been killed, many by barrel bombs dropped on neighbourhoods by the regime and its affiliates. Millions more have been wounded and displaced, while the regime has forcibly disappeared thousands of others.

President Bashar al-Assad’s terrorism has exceeded that of his father and uncle, who destroyed the city of Hama with heavy artillery in the early 1980s to quash the Muslim Brotherhood.

Saddam Hussein acted similarly with his massacres against Shia Muslims and Kurds in Iraq, including the 1988 Halabja chemical attack.

Former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi also slaughtered his opponents: the infamous massacre at Abu Salim Prison in 1996 saw up to 1,200 people killed.

This state apparatus has become increasingly brutal in the wake of the Arab Spring, amid fears its tyranny would be dismantled

In Algeria, tens of thousands of people fell victim to repression and despotism during the 1990s conflict known as the “Black Decade”, triggered by the state and military coup against a nascent Islamic democratic experiment.

The decade of bloodshed ultimately ended with a national reconciliation agreement launched by recently deposed president Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

In Sudan, the regime of former president Omar al-Bashir committed horrific massacres in Darfur and elsewhere, and was responsible for dividing the country and draining its wealth.

In Tunisia, thousands were detained and tortured from the era of Habib Bourguiba through to the regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, until the uprising that spurred his downfall began in 2010.

Gradual acts of murder

In Egypt, since the era of Gamal Abdel Nasser, authoritarianism has been responsible for the killing of thousands of people through suppression and torture. The killings that followed the 2013 coup, particularly the Rabaa massacre that resulted in more than 1,000 deaths, remain the most significant in Egypt’s modern history.

The Saudi regime has done and continues to do the same, as it liquidates activists and political opposition, whether in Qatif and other regions of the kingdom or abroad, as in the case of the late journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

In Morocco, protests were suppressed throughout rural regions and cities from the 1950s until today.

More gradual acts of murder also take place within Arab prisons and detention centres, far from any surveillance or media, through medical negligence, as in the case of former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi, who died in June while standing trial.

Killings have also taken place at the hands of security and military forces in a number of Arab countries under the pretext of the “war on terror”, which is what Khalifa Haftar’s militias are currently practising in Libya.

If we also consider the deaths caused by the failure of various state policies - whether in the health sector, or through institutional neglect in sectors such as transport - the number of victims is ultimately in the millions.

A killing machine

These crimes and others have transformed the Arab state from an administrative system designed to serve its citizens, into a deadly killing machine. It has become an apparatus of organised crime, specialising in looting public wealth. Anyone objecting to the state of affairs is killed or forcibly disappeared.

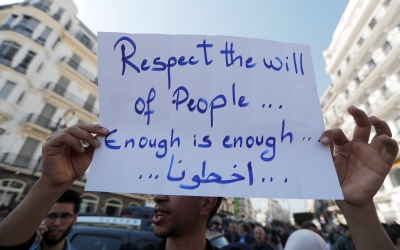

This state apparatus has become increasingly brutal in the wake of the Arab Spring, amid fears its tyranny would be dismantled.

The Arab world might not be unique in this regard, as the crimes of dictatorship and authoritarianism are as old as humanity.

But the pretensions of the Arab state, as well as its ruling elite and those in its orbit, that it holds the right to power in the post-independence era and is capable of practising this power, runs counter to its crimes against its people.

In this way, it does not differ greatly from the violent extremist groups that for decades have been waging a war against it. Groups such as the Islamic State kill in the name of religion, while the Arab state murders in the name of defending security, stability and status.

And while the terror of these extremist groups is transient, the terror of the Arab state persists as an integral part of the daily routine of Arab citizens.

In fact, state terror in the Arab world has become more systematic and visible and will eventually lead to the destruction of Arab societies.

Arab citizens have nothing left but hope for a more dignified and less violent life which they will continue to aspire and fight for peacefully and democratically.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].