Arabic and AI: Why voice-activated tech struggles in the Middle East

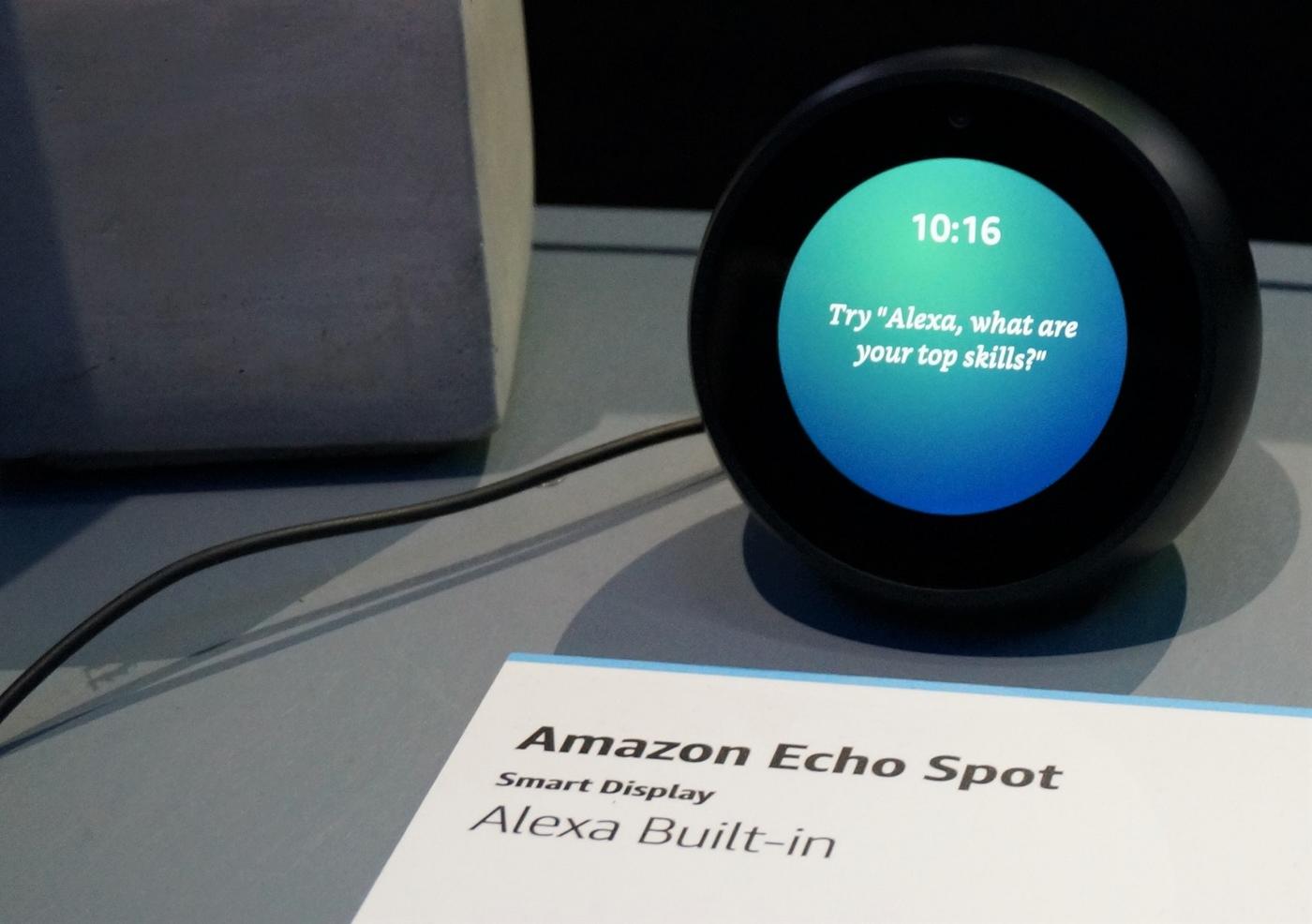

Alexa can’t speak Arabic. Neither can Cortana. Siri can understand standardised Arabic - but not dialects. Google Translate is barely accurate.

When it comes to understanding the world’s fifth most spoken language, 21st century technology is behind the times.

“Arabic is spoken by about 300 million people worldwide, and it’s the religious language for about 1.5 billion,” says Mustafa Jarrar, a computer scientist at Birzeit University in Ramallah. “But it’s one of the least represented languages in technology.”

Jarrar, and other computer scientists from across the Middle East, want to change this. They’re working to expand the inclusivity of the tech world by improving AI’s grasp of Arabic beyond the standardised version.

Their hope? That the programs, apps and voice services which are becoming increasingly prevalent can finally understand Arabic’s 30 or so dialects.

Ghost in the machine

The branch of artificial intelligence (AI) that allows computers to process and interpret human language is known as Natural Language Processing (NLP).

When we ask Alexa, Amazon’s voice-activated virtual assistant, to play a song, she uses NLP techniques to process our voice command. This technology is also used by automated translation tools such as Google Translate.

But the way computers accumulate languages is, unsurprisingly, different to the process used by humans.

“Computers learn languages through statistics,” explains Jarrar. In order to translate one language into another, he continues, “the computer collects millions, sometimes billions of sentences with the same meaning in the two different languages, and from this it can deduce which translation is the most frequent.”

Researchers also ascribe characteristics to words, such as the word’s position in a sentence or its prefixes and suffixes, creating a body of data on which the computer can base its statistics. The more data it accumulates, the more accurate it can be.

All this means that data is king when it comes to teaching languages to a computer. But, Jarrar says, it's hard to accumulate enough of it when it comes to Arabic dialects.

'On social media, Arabs write how they speak - phonetically'

- Mustafa Jarrar, Birzeit University, Ramallah

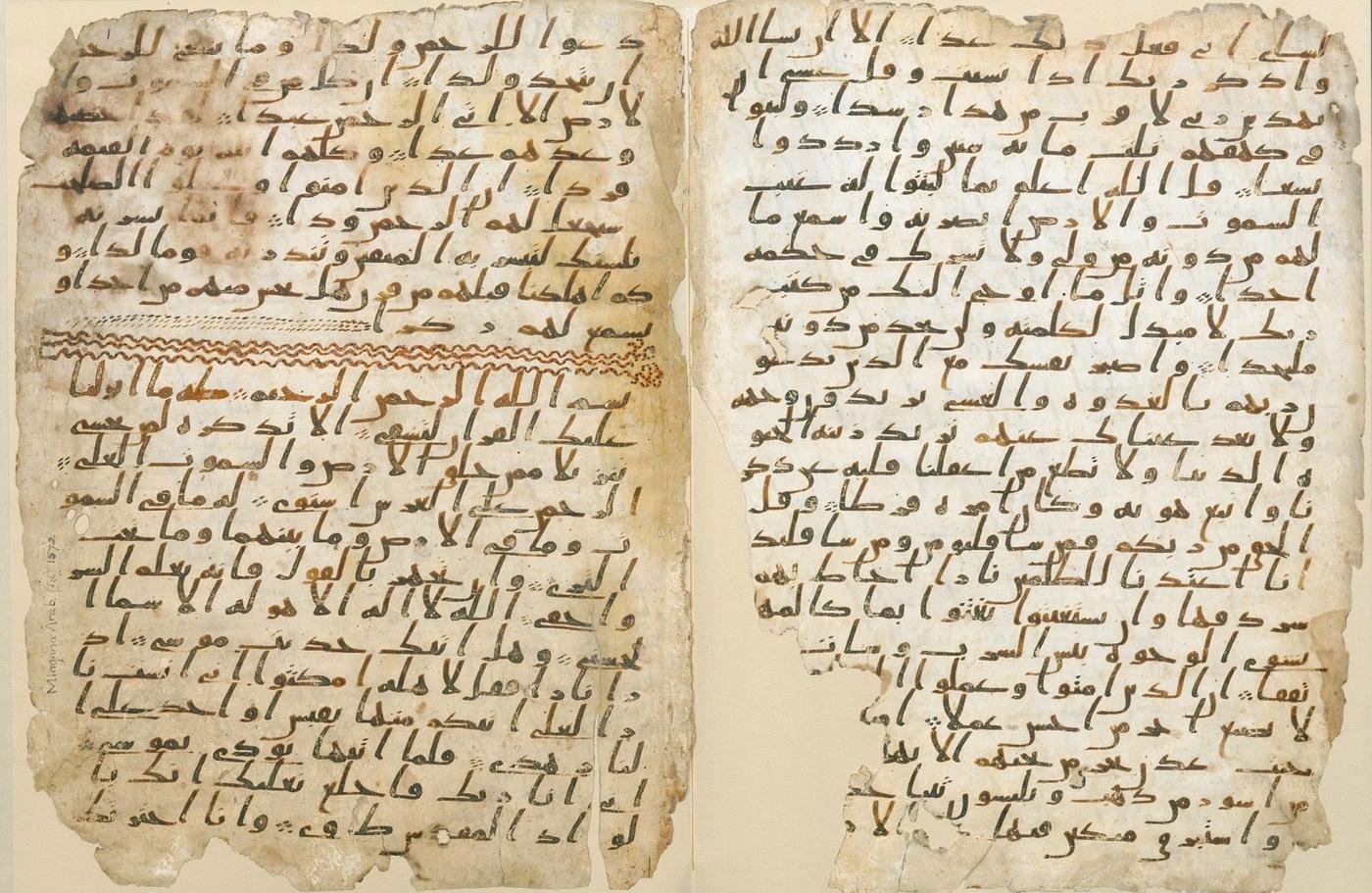

“Before social media there wasn’t really any of the dialect written down,” says Jarrar, whose speciality is the Palestinian dialect. “It was just how you spoke to your family and friends. This means that on social media, Arabs write how they speak - phonetically.”

Arabic dialect only began to be written online after languages such as English, French and Spanish, which use the Roman alphabet. It means that scientists like Jarrar have less data with which to train AI than colleagues working on other languages. (In comparison, if someone wants to work on a project using NLP techniques in English, then the data is already there for them. “Everyone is working on English,” Jarrar says, “English is done.”)

Developing Palestinian dialect, Jarrar says, has involved collecting huge amounts of text, then going over every word and assigning it defining characteristics or values for the computer to learn, such as where it occurs in speech, its prefixes, its suffixes, its meaning in English and its meaning in standard Arabic.

But in 2016, the breakthrough came. “Now computers can understand Palestinian dialect,” says Jarrar, who was only the second person to train a computer in an Arabic dialect: the first was the US Army, which achieved the same for Egyptian.

The enigma of Arabic

Teaching Arabic to computers is not just bedevilled by a lack of data: the language also has several traits that can add layers of ambiguity and difficulty.

Ali Farghaly, an NLP researcher from Egypt, says: “Arabic doesn’t have capitalisation, which is a way to indicate proper names of people, places, companies. Arabic letters also change their shape every time their position in the word changes.”

In addition, longer words in Arabic can be created by stringing smaller elements of language together.

“A complex word can be analysed into a subject, a verb and an object,” Farghaly says, “and many times a complex word can be broken down in three or more different ways, which increases ambiguity.”

Take, for example, the phrase “He killed them”. In English it has three parts: the subject (“he”), verb (“killed”) and object (“them”). But in Arabic this sentence has just one word: “qatalahum” (قتلهم ).

Farghaly gives another example. “A word in Arabic like 'wafi' can be considered one word meaning 'faithful' or it can be broken down into two words: 'wa' meaning 'and' and 'fi' meaning 'in'. The fact that words like this can be deconstructed in more than one way makes disambiguation in Arabic a challenging task in NLP.

Why Arabic is under-funded

Such problems in machine learning are common and scientists have been trying to address them since the early 1980s.

Research was accelerated following one defining event. “After 9/11, the US government generously funded universities, research centres and private companies to work on Arabic NLP,” Farghaly says.

'If we’d made an English chatbot, the market it for it would have been a lot bigger'

- Abdallah Faza, Arabot

“American scientists implemented state of the art technology to develop Arabic machine translation systems. This had a positive impact on Arabic NLP work in the Arab world too.”

Despite this upsurge, Arabic - and dialects in particular – are relatively under-resourced, with key companies like Amazon, Google and IBM funding them less than Latinate languages.

Abdallah Faza, a tech entrepreneur from Jordan, says that this lack of investment is largely because there are greater incentives to develop products in other languages which are more frequently used, such as Mandarin, or have more commercial application, such as Spanish.

Faza created Arabot, one of the first chatbots in Arabic. The programme allows customers to ask questions about products online, which are then answered by a computer.

“If we’d made an English chatbot, the market it for it would have been a lot bigger,” he says. “For chatbots, IBM is the main competitor, but they are working at a basic level in Arabic.”

Other projects with commercial appeal are emerging. Earlier this year, the Abu Dhabi state broadcaster, Abu Dhabi Media, announced it was developing the world’s first Arabic-speaking AI news presenter.

Mawdoo3, a company from Jordan, said last year that it had begun work on a virtual assistant - like Alexa or Siri - called Salma that will work in Arabic and all its dialects.

UN: Computers need to understand

Nor are these advances limited to the commercial sector. A team of researchers at Lebanon’s American University of Beirut, for example, are working on improving Arabic NLP so it can be used to analyse social media content to pick up important but undetected events and information.

“We develop and use NLP techniques to analyse Arabic text including social media - Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook and Twitter," explains Fadi Zaraket, who leads the team.

"The analysers we develop can be used to detect mentions of people, places, violence, complaints, and other events on social media. This helps complement the picture depicted by mainstream media, by picking up events the media may not have picked."

Having computers understand Arabic is critical to the project, because it allows the identification of events that haven’t been spotted by the international community.

'A computer can process the content, but it can’t truly understand the meaning of the words'

- Mustafa Jarrar, Birzeit University, Ramallah

International organisations are also detecting the potential. Martin Waehlisch is a political advisor at the United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, part of a team working on developing a system that will use computers trained in Arabic dialects to conduct mass focus groups. The system will ask thousands of people in a conflict zone questions, and then sift through the answers to find common responses.

“Natural Language Processing in Arabic and other languages has been a long-standing issue for public and political affairs,” explains Waehlisch, “because we are interested in understanding people's concerns and needs better, which can help us with designing more sustainable dialogue and peace processes."

The system will allow the UN to get a real-time indication of public feeling and sentiments in areas with limited physical access or other restrictions. Getting the system working in Arabic is paramount to the project, given conflicts across the region.

Jarrar, for one, is optimistic about the future of computers and Arabic, and proud of the progress already made. “NLP for Arabic is a lot stronger than it was five or 10 years ago,” he says.

Once the processing of the dialects is completed, the next challenge will be to work on computers truly understanding the language, he explains, instead of predicting translations based on statistics.

“If you tell a computer you’re going on holiday, it can translate that, but then if you ask it the question: ‘Where am I going on holiday?’, it can’t answer,” Jarrar says. “It can process the content, but it can’t truly understand the meaning of the words. So that’s the next thing to work on.

“English is more advanced than Arabic in this next step, but even then it’s not perfect. But I think in a few years we’ll be able to ask Siri any question and she’ll answer. And I think it’ll be the same in Arabic then too.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].