The Zionist quest for Palestinian absolution is a fantasy

Earlier this month, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu explained the main obstacle to a “solution” with the Palestinian people.

Along with Education Minister Rafi Peretz, Netanyahu attended a ceremony to mark the start of the school year in the Elkana colonial settlement in the Occupied West Bank and gave a "lesson to first grade pupils". When a student from the high school at the same settlement asked him about the “Israeli-Palestinian conflict”, Netanyahu delivered a rehearsed answer.

“The root of the conflict is the Palestinian refusal to recognise the state of Israel within any borders whatsoever and to recognise the state of the Jews within any borders whatsoever … I emphasise this and strive for this, that the recognition of the national state of the Jewish people must be demanded of them,” he said. “This is the first - but not the last - component of any solution.”

Seeking absolution

Netanyahu’s assessment is accurate. The “root of the conflict” is the refusal of colonised Palestinians to recognise the right of European Jews to colonise their country, expel them, steal their lands and establish a settler colony with racial privileges to the Jewish colonists that are denied to the native Palestinians.

If Palestinians were to accept the right of Jews to colonise their lands, expel them from their homeland, and oppress those they could not expel, then a “solution” would indeed be found.

The colonisers’ wish that the natives they colonised and expelled would absolve them of their sins is anchored in the fantasies of the Zionist movement since its birth. In his 1902 futurist novel The Old-New Land, the founder of the Zionist movement, Theodor Herzl, sought absolution from the Palestinian people whose lands he sought to colonise.

This disavowal ensures that Zionists and Israeli Jews should never feel guilt about their settler-colonial venture

In his novel, he includes a token Palestinian character named Rechid Bey, who explains to European Jewish colonists what their colonisation had done to Palestinians. While Rechid Bey explains that Palestinians had orange groves and other cultivation before Jewish colonisation, a Jewish colonist named Steineck replies: “I don’t deny that you had orange groves before we came, but you could never get full value out of them.”

Rechid Bey agrees and explains how the profits of Palestinian landowners “have grown considerably. Our orange transport has multiplied tenfold … Everything here has increased in value since your immigration.” This is when a European Christian visitor interrupts, asking: “Were not the old inhabitants of Palestine ruined by Jewish immigration? And didn’t they have to leave the country? … That individuals here and there were the gainers proves nothing.”

Rechid Bey quickly retorts: “What a question! It was a great blessing for all of us.” The European Christian persists: “Don’t you regard these Jews as intruders?” This is where Herzl gears up to the most wished-for absolution that all oppressors seek from those they oppress. Rechid Bey responds: “Would you call a man a robber who takes nothing from you, but brings you something instead? The Jews have enriched us. Why should we be angry with them? They dwell among us like brothers. Why should we not love them?”

'They did not exist'

The fantasy of the Palestinian who can grant absolution to colonising Jews persisted even in the most important Hollywood film about the Zionist conquest of Palestine, Exodus. In this propaganda film, only one Palestinian, Taha the Zionist collaborator, is allowed to speak. He is permitted to do so in order to praise Zionism and toast the conquest of his people’s land and lives.

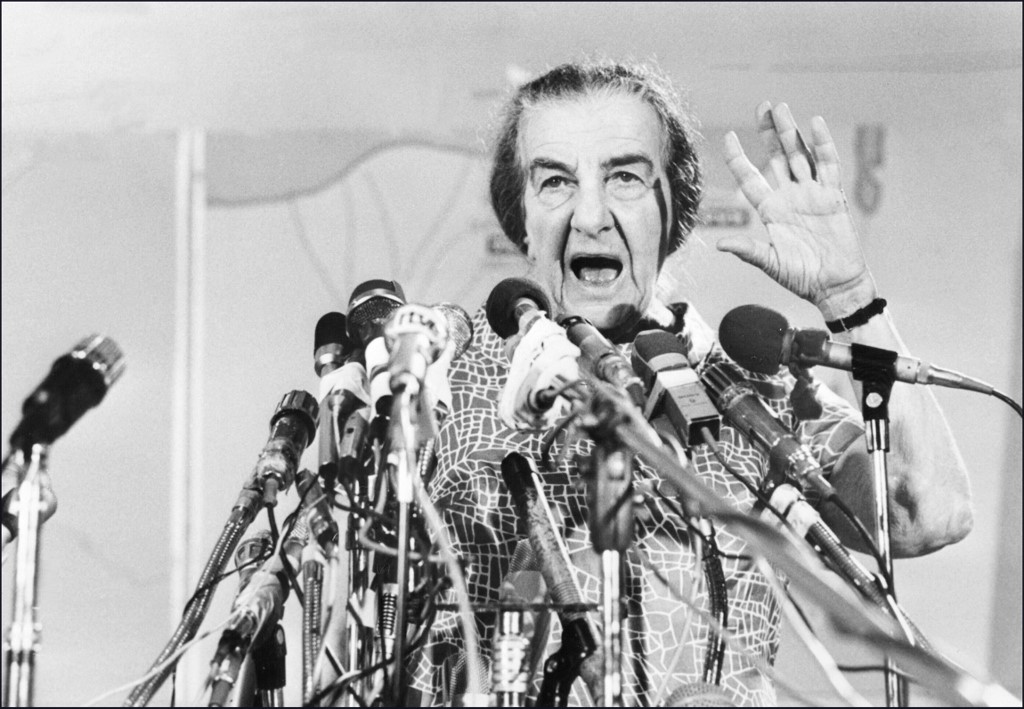

It was former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir who did not seek absolution from the Palestinian people, by insisting in 1969 that they had never existed: “It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine considering itself as a Palestinian people and we came and threw them out and took their country away from them. They did not exist.”

For Meir, the establishment of Israel did not dispossess anyone, and certainly did not constitute a loss for Palestinians. This disavowal ensures that Zionists and Israeli Jews should never feel guilt about their settler-colonial venture, while also admitting that they would have to feel guilty had there in fact been a Palestinian people that they dispossessed - except that, according to Meir, they did not.

The fantasy of the Palestinian who would absolve Zionist colonists of their guilt became a reality in the Palestinian collaborators recruited by the Zionist movement before and after the establishment of the settler colony. Still, this was a far cry from being granted absolution by all Palestinians.

Demographic concerns

As the resistance of the Palestinian people continued and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) came to lead that resistance from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s, the Zionist search for Rechid Beys proceeded apace.

When the PLO succumbed to its current fate as a collaborator with Israel in oppressing Palestinians and suppressing their resistance, the Zionists thought their fantasy was being realised.

It is true that Yasser Arafat partially embodied Rechid Bey when he spoke in 2002 of the Palestinian right of return: “We understand Israel’s demographic concerns and understand that the right of return of Palestinian refugees, a right guaranteed under international law and United Nations Resolution 194, must be implemented in a way that takes into account such concerns.”

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas went further in 2012: “Palestine now for me is ‘67 borders, with East Jerusalem as its capital. This is now and forever ... This is Palestine for me. I am a refugee, but I am living in Ramallah. I believe that the West Bank and Gaza is Palestine and the other parts are Israel.”

Still, this was not enough for Israel. The Israelis have found minor Palestinian characters to play the role of Rechid Bey - but to no avail. The search for an exact and credible replica of the fictional Rechid Bey continues.

History of land theft

Netanyahu’s response to the student in Elkana reminds me of an anecdote involving a dear friend of mine from university days. A couple of decades ago, my friend, an anti-Zionist American Jewish woman, was concerned about raising her children as both Jewish and anti-Zionist. When her son was about five, she took him to her local Jewish congregation so that he would learn Jewish ethics and religious traditions, but when the congregation was preparing to celebrate Israel’s “Independence Day”, my friend refused to attend with her family.

The Israelis have found minor Palestinian characters to play the role of Rechid Bey - but to no avail

Her young boy asked why they were not attending. She explained that in 1948, the Zionists stole the land of the Palestinians, and that they celebrate this theft every year. She then gave him the example of someone stealing a dollar from someone else and then celebrating the theft. Israeli Independence Day is “I stole your dollar day”, she told him, affirming: “We do not celebrate ‘I stole your dollar day’.” The child learned the lesson and grew up to be an anti-Zionist, ethical Jewish adult.

Until and unless Israeli Jewish children are taught this same lesson, the “solution” that Netanyahu seeks will never be found - and unless Israel is able to transform all Palestinians, let alone all Arabs, into Rechid Beys, the Zionist fantasy that has persisted from Herzl to Netanyahu will remain largely unfulfilled.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].