Future or funeral? Israel's Labor party could be on the verge of extinction

Anat Frank is old school Labor.

The 57-year-old dancing instructor is a card-carrying party member, lived for decades on a kibbutz and has spent the past five years here in the one-time Labor stronghold of Tel Aviv.

'To see Labor go down, down, down over the years has been incredibly sad'

- Anat Frank, 57, dance instructor

“I’ve been with Labor since I can remember,” she tells Middle East Eye as she drags on a cigarette outside her party’s final election rally.

“But I don’t know if it will get enough votes to enter the parliament this time. To see Labor go down, down, down over the years has been incredibly sad.”

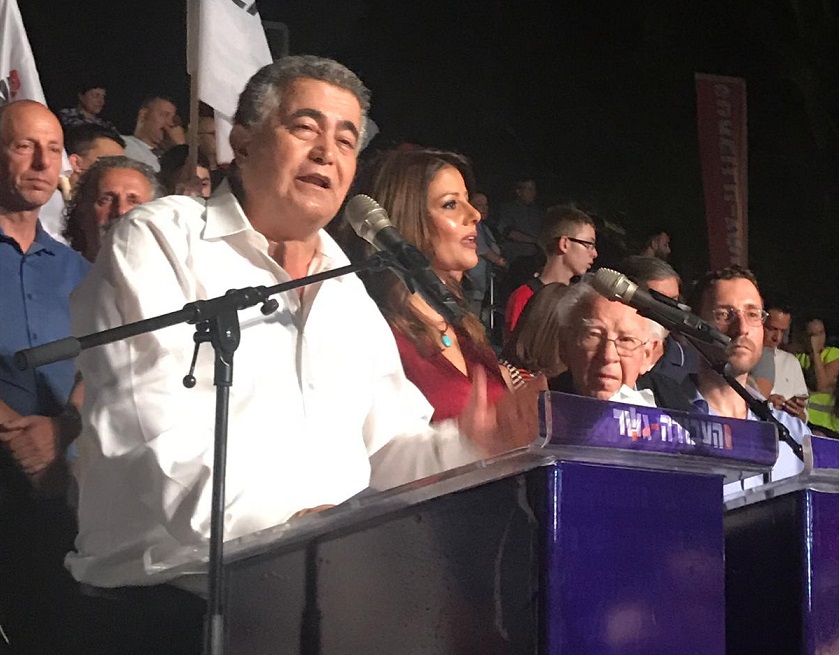

Metres away, Labor leader Amir Peretz and his new running mate, Gesher party head Orly Levy-Abekasis, are wrapping up speeches at an event designed to energise their support ahead of Tuesday’s election.

The mood is generally upbeat on this sticky September night. The charismatic Peretz is rousing, the crowd is chanting Levy-Abekasis’s name and there’s free ice cream.

But only a couple of hundred people have turned up, a far cry from the final rallies of Labor’s rivals, let alone the party’s events in years past when it used to be the dominant force in Israeli politics.

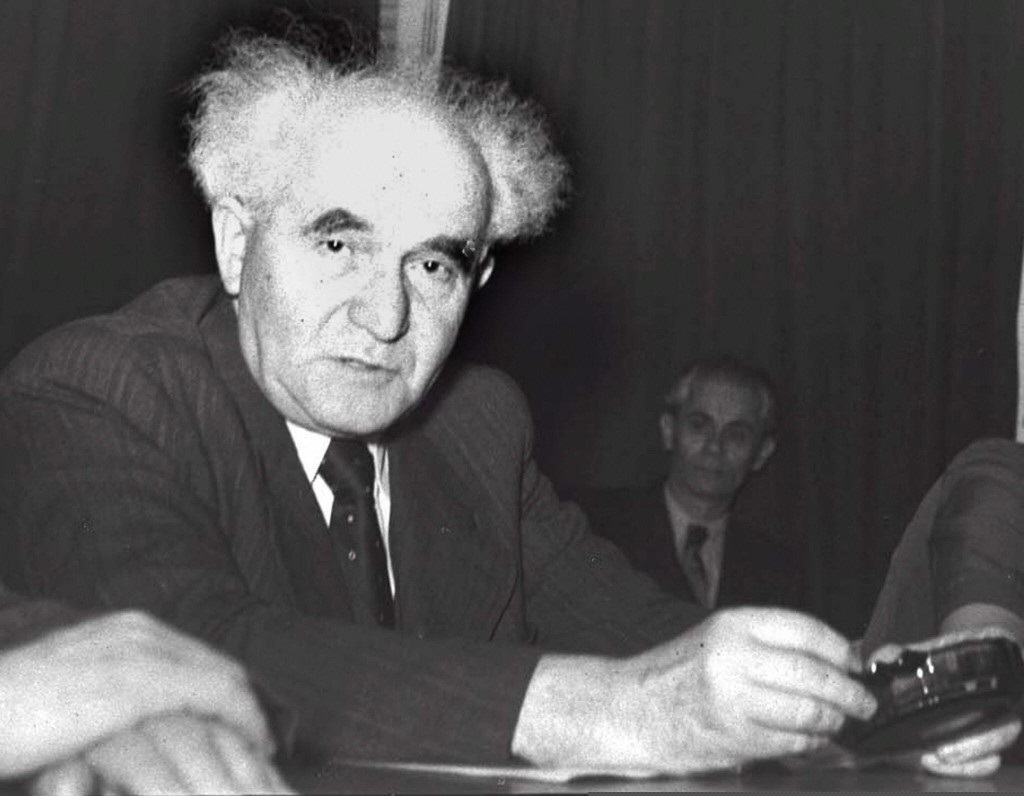

In different guises, Labor ruled Israel for its first three decades and has boasted founding father David Ben Gurion, assassinated prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and peace advocate Shimon Peres as its leaders.

Since 1992, however, it has seen its share of the vote drop from 37.7 percent to just 4.4 percent in April’s inconclusive election.

Now the pre-election polls are predicting that Labor is struggling to even pass the 3.25 percent threshold required to enter Israel’s parliament, the Knesset.

The party that constructed much of Israel’s infrastructure, allowed the first illegal settlements to be built in the occupied West Bank and negotiated the Oslo Accords could be on the brink of extinction.

A new look

Following Labor’s poor showing in April’s election, when the party won only six seats, Peretz has attempted to take things in a new direction.

The Moroccan-born Israeli, who was Labor leader from 2005-2007 and has served as a minister in previous governments, made one profound cosmetic change: he shaved off his moustache for the first time in 47 years.

But Peretz has also attempted to give Labor a different look, by uniting the party with Gesher and Levy-Abekasis, who is a former member of Avigdor Lieberman’s right-wing Yisrael Beiteinu party.

At campaign events over the past weeks, he has appeared confident, affable and approachable.

He has sharply rebuked anyone asking why he was allying Labor with Levy-Abekasis, who comes from the Israeli right and whose party fell far short of the threshold last time around, rather than the Democratic Union on the left.

'To be honest with you, I didn’t vote for Peretz to be leader. But after seeing him and speaking to him, I have changed my mind'

- Yael Kami Weitzman, Labor member

“To be honest with you, I didn’t vote for Peretz to be leader,” says Labor member Yael Kami Weitzman as he holds a placard up in the crowd.

“But after seeing him and speaking to him, I have changed my mind and I see that he is good. He has a lot of experience.”

While he may be attacked for bringing on Levy-Abekasis, whose father was once a heavyweight in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party, Labor supporters at the rally seem generally enthused.

“I like Orly Levy. I think it’s really positive to bring on some new people,” educator Mika Barkat tells MEE.

“Peretz is doing the right thing by appealing for right-wing votes.”

Her friend Sigal Fine concurs: “The concept of left and right doesn’t reflect how things are in Israel now, things are different. And I agree with Levy’s social stances.”

'Iron Dome for social issues'

The Labor-Gesher ticket plays lip-service to many issues and casts itself as the so-called “peace camp” that seeks to reach an amicable solution with the Palestinians and neighbouring Arab countries.

But really it is doubling down on one thing: socio-economic issues.

In nearby Givatayim, a few days before the rally, Peretz pointed to the Iron Dome anti-missile system he developed in 2006-7 as defence minister as an example of his reliability.

“I created the Iron Dome. Now I want to create an Iron Dome for social issues,” he said.

The Labor-Gesher plan is detailed and expansive and calls for 30 billion shekels ($8.5bn) a year to be spent propping up the most vulnerable parts of society.

It envisions the minimum wage being raised from 29 to 40 shekels an hour, 200,000 public housing units constructed and the creation of hundreds more hospital beds, among other things.

So far so good. But even liberal Israeli newspaper Haaretz has lambasted their proposal for being nowhere near costed properly.

Naftali Bennet, of the far-right Yamina party, suggested it risked “turning Israel into Venezuela”.

However, for Yael Shallish, a nurse in her 50s, the mere talk of putting funds into struggling sectors is refreshing and necessary, while other parties argue over issues such as security and secularism.

“I like that Peretz calls himself a socialist,” she tells MEE. “As a nurse, I can see how crowded the hospitals are and the damage that is being done, and that needs to be addressed.”

Big risk, big reward?

The socialist tinge to Labor has been missing for some time.

According to veteran political analyst Meron Rapoport, Labor’s issues stretch back 25 years, when it broke with the trade union movement that had been a bedrock of its support.

'What Peretz is doing is important and brave, but the challenge might be bigger than himself'

- Meron Rapoport, Israeli political analyst

“It turned towards a more neoliberal discourse, which was based in part on its constituents, which had become the economic elite,” he tells MEE.

Those economic elites, the majority Ashkenazi Jews of European origins, have drifted towards the new Blue and White party, leaving Labor totally exposed.

Peretz, Rapoport says, seeks to now appeal to working-class voters, often Mizrahi of Middle Eastern origins, with a socio-economic platform.

Both Peretz and Levy-Abekasis are Mizrahi, a community that traditionally supports Likud.

“Labor is hoping by standing on a clear social democratic platform it can break the traditional left-right deadlock and block the right from automatically achieving a majority,” Rapoport says.

That shift has encountered two problems. First, it has alienated some of Labor’s traditional voters. Second, it is proving difficult to prize working-class and Mizrahi voters from the right.

“The new strategy is a big challenge and risk. What Peretz is doing is important and brave, but the challenge might be bigger than himself,” Rapoport says.

“In the long run, it is a risk worth taking because Labor could not survive as it was.”

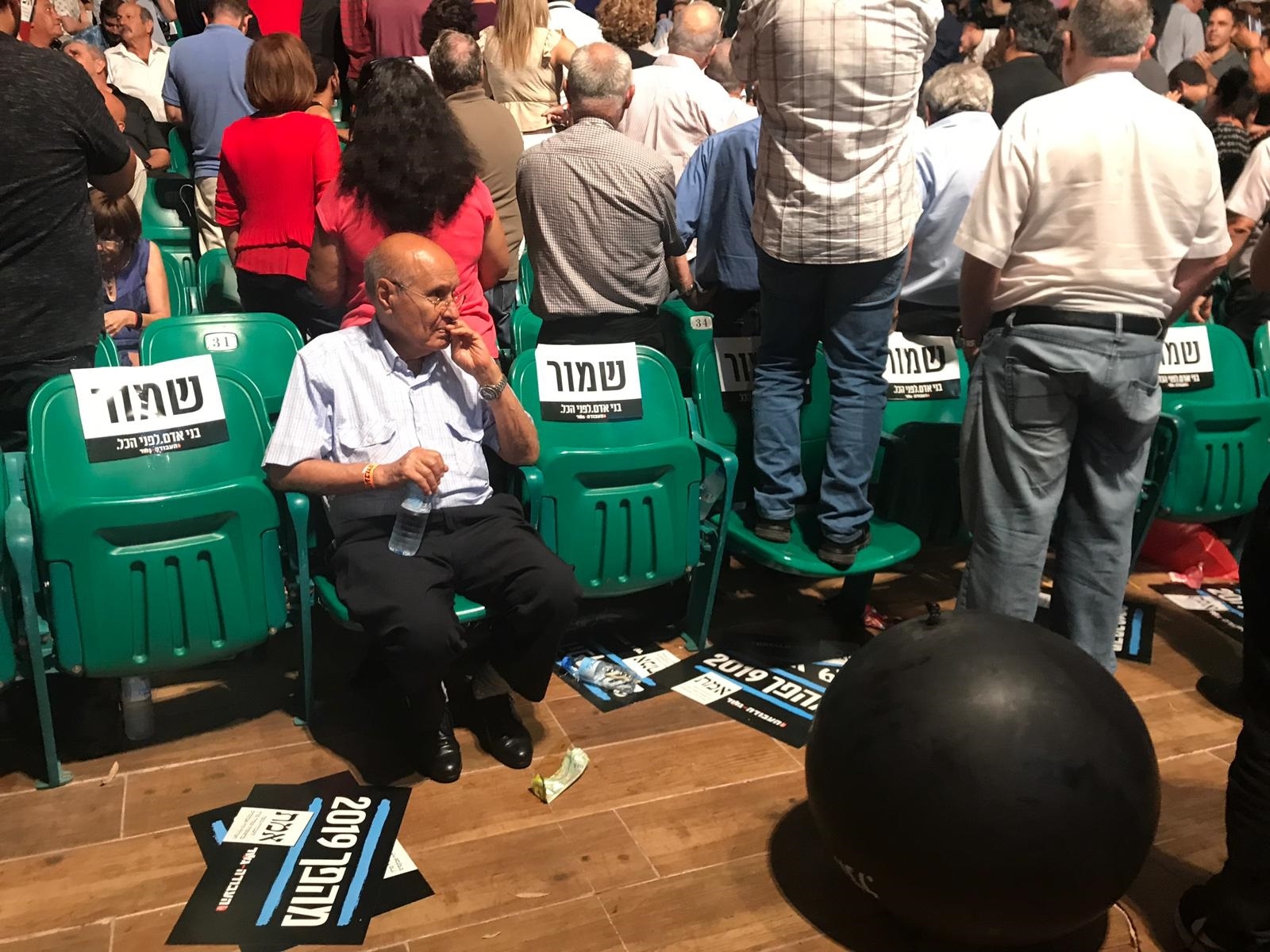

Back outside the rally, Frank, the dancing instructor, is watching people file out of the outdoor theatre and into the dark of Tel Aviv’s luscious Yarkon Park.

“We’re not going to do any better this time,” she sighs. “I nearly didn’t come tonight, but I made myself in the end.

“I don’t know what is wrong. We’ve stopped talking the language of the people.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].