Shakespeare, museums and Baghdad: 'I’ll write what I wanna write'

On the first day of rehearsals for the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of A Museum In Baghdad, writer Hannah Khalil looked around the studio at the big cast. All but two were – like herself - of Arab descent.

“It was an emotional moment,” says the Irish-Palestinian dramatist. “I felt really proud, because that’s what I wanted to do, I wanted to write good, exciting, meaty, real parts for non-white actors.”

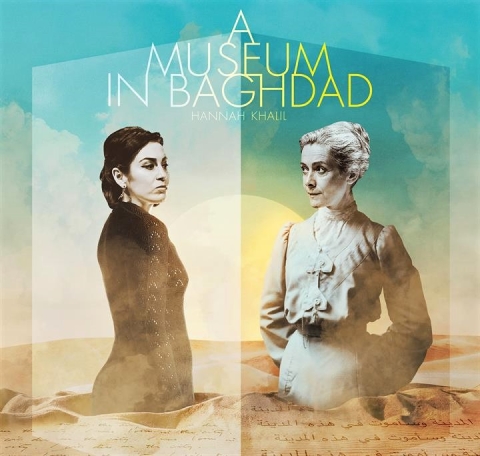

The play, which opens on 11 October in Stratford-Upon-Avon, tells how famed British colonial administrator Gertrude Bell created the National Museum of Baghdad during the 1920s; and how, in 2006, an Iraqi female archaeologist tries to save it from the chaos caused by the US-led invasion.

Although based on real people and events, it does not conform to the rules of linear historical drama: characters flit across time frames, speaking to each other and the audience as the history of Iraq is collapsed into the microcosm of the museum and its fate.

“The play is quite unusual in structure – it’s not a traditional three act play,” says Khalil. “And I was slightly nervous that a company like the RSC would make it fit a bit more neatly, but not at all, actually it’s been quite the opposite. They’ve really pushed me to be as bold as I can and have embraced the madness of it.”

Beyond Shakespeare

The RSC is globally renowned for its Shakespeare productions - but the company also supports new writers and new work, says Erica Whyman, RSC deputy artistic director and the director of Museum. Crowd pleasers including the musicals Matilda (2010) and Les Miserables (1985) both began life at the RSC.

As Khalil says: “Often people think it’s the RSC, they just do Shakespeare, but it’s not true, they’ve always done new plays. [Playwright Harold] Pinter was one of their key people – they premiered most of his work.

“I think it’s also true to say that the people who write those plays don’t normally look like me or come from where I come from.”

The play is also breaking ground for how it tells a story of the Middle East which is not about extremism or violence, as well as those who tell it.

“I pretty much haven’t met anyone in this play in fiction,” says Whyman. “Even Professor Woolley, who is the only white man in the play, feels quite fresh - but more vividly two Iraqi women archaeologists having a conversation with each other and holding the stage feels new and really interesting.”

One of the reasons Khalil writes, she says, is to let people of Arab and non-white descent play fully rounded characters.

“I know so many actors from a similar heritage as me who are forced to go for the same stupid roles again and again, that are so narrow. I have always written Arab characters and tried to make them three dimensional, and undercut a white middle class audience’s idea of what an Arab person is. I’ve always tried to redress that balance in my own little way.”

'If they don’t like it, tough shit'

Khalil grew up in Dubai, where her Palestinian father ran a hotel. “It was the 1980s, it was a very different place than it is now. It was hotel, desert, road, a bit more desert, our compound, desert. I’d walk across the desert to go to school. It was really magical.”

The RSC approached her last year, following her award-nominated play Scenes From 68 Years, about Palestinians who lived through the Nakba (Catastrophe) during the creation of Israel. Despite the violence of those events - more than 700,000 were forced from their homes – Khalil’s piece contains more laughter than suffering.

Scenes, which opened at London’s Arcola Theatre in 2016, is Khalil’s most successful play: it’s had a reading in New York, a production in San Francisco and is now being rehearsed in Tunisia, where it will be performed in a mixture of Arabic, English and French from mid-October - three days before Museum opens in Stratford-Upon-Avon.

'People who are of Palestinian heritage or from the MENA region, who are in the diaspora, are so desperate to see themselves represented. It never happens'

- Hannah Khalil, playwright

Her Palestinian heritage is important to Khalil, be it through food or the stories of her grandmother. Yet for years, she says, she avoided writing about it.

“It was scary. ‘How can I talk about this huge subject - everyone is going to tell me I’m stupid and I’m wrong.’ And then I thought: ‘I’ll write what I wanna write and they can write what they want to write and if they don’t like it, tough shit’.”

Khalil says she owed it to her audiences to put their mostly neglected stories, such as that of the Iraqis in A Museum in Baghdad, on stage. “People who are of Palestinian heritage or from the MENA region, who are in the diaspora, are so desperate to see themselves represented. It never happens. Or if it does, it’s in a way that’s disappointing.”

Colonials and invaders

For Museum, Khalil started writing a historical drama about Bell. Then, around 2010, she attended a talk by archaeologist Lamia al-Gailani Werr, who returned to Iraq after 2003 to become director of the country’s National Museum.

The period marked some of the museum’s darkest days, as robbers looted its halls and display cases despite reassurances from the US authorities that they would protect it. (“Just one or two tanks would have prevented all this destruction,” Ghailani Werr complained at the time).

Khalil gradually built up the idea of a play set during two time periods, the one the RSC eventually read and signed up for.

RSC actor Emma Fielding plays the character of Bell in Museum. She says that the play is not one in which white characters attempt to save the natives and that her character is sympathetic, if inevitably flawed. “Now you cannot have a posh lady in a big hat saving the world any more,” she says.

Yet Khalil insists that the piece is not a black-and-white picture of Iraq’s depredations by Western colonialism: it’s a more complex work than that.

“Probably when I started researching Gertrude Bell I wanted to hate her, and thought: ‘She’s like all of them.’ But she loved Iraq, she loved Iraqis, she loved the Arab world.

"I don’t think the way she went about doing things was right, but she meant well. And that’s the thing that’s really complicated. She even advocated at one point what the people of the region wanted: fluid borders. She tried to suggest that but she was laughed out of town.”

Khalil is more certain about the invasion of 2003 and what followed. “That was a total botched job and should have never happened.”

One of the RSC’s corporate sponsors is BP, the British energy giant that first found oil in Iraq during Bell’s era, then quit in the 1970s when Iraq nationalised the industry. It was quick to return following the invasion and now pumps 1.5 million gallons of oil a day out of the Rumaila field.

Oscar-winning actor Mark Rylance quit the RSC in June over its sponsorship by BP, in line with the growing calls from campaigners to halt fossil fuel extraction because of global warming.

Whyman says the sponsorship issue is “complex” but that it does not affect the RSC’s creative output or ability to examine Britain’s role in the Middle East.

“A Museum in Baghdad is a good example of us choosing to make work which raises difficult questions about British actions and responsibilities in the world, in this case in Iraq,” she says.

“We welcome any debate that flows from the work we choose to make on stage, and we recognise the strength of feeling in recent debates about arts sponsorship, climate change and corporate responsibility.”

'Right now I feel like a fighter'

Rendah Heywood, a British actor of Iraqi descent, plays Ghalia, the director of the museum in 2006, based in part on Gailani Werr, who died earlier this year.

She sees her character’s role “to build a sense of unity for the Iraqi people who have lived through sanctions and war. To basically try to give them their identity and to try to remind them how incredible this civilisation was.”

She says she feels close to Ghalia’s predicament as a diaspora Iraqi returning home amid the chaos. “I can relate to my character hugely in that I’ve been brought up British, I’ve never visited Iraq, I’ve visited the Middle East quite extensively, in Jordan, Dubai, Oman.”

Most of her Iraqi family now live in the UK - her father last went home the week Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990.

“When I read the play, it’s the diaspora syndrome of seeing wars unfolding in countries you are connected to. I feel it’s so difficult because I’m separated from it but I’m deeply connected through the language, the food, the culture. I’ve been brought up with that.”

Iraqi actor Rasoul Saghir, who plays the museum caretaker Abu Zaman, is an important presence in the rehearsal room, linking other members of the cast and crew to a lived knowledge of the country. (The play’s assistant director, Yasmeen Ghrawi, is also Iraqi).

The project is immensely personal for him, he says, and often emotionally challenging - “It is a big challenge, right now I feel like a fighter” - reminding him as it does of Iraq’s bloody history.

“It is a difficult and terrible journey, a very bad history to remember."

The son of an Iraqi communist who opposed Saddam Hussein, he was jailed and tortured by the regime, eventually fleeing the country - and conscription - via Jordan as war loomed in 1990.

“We have some scenes in this play that took me back, really, because there are some things I have been there," he says, referring to events in his life, or those of family members. "My father was also a communist, so he is against Saddam Hussein, he was imprisoned and tortured, yani [you know]."

After years stuck in Yemen, Saghir resettled in Holland in 1996. He was teaching theatre in Kuwait when he got a call from a friend about the RSC part earlier this year.

“It is a big dream for me, really,” he says. “To be the witness to Iraq’s history in the play is, as an Iraqi, hard. Sometimes I feel very, very emotional, because I left my country as a man, not as a child, yani, so there is half of me, I’m like Abu Zaman,” he laughs.

After taking the part, Saghir went to Baghdad and read the whole play to his father. At the end his father said of Khalil: “Yes, that’s right, that’s it, she’s Iraqi!”

That, says Khalil, is the accolade she cherishes the most. “I was like, that’s very nice, I’ll take that.”

A Museum In Baghdad runs from 11 October to 20 January at the RSC in Stratford Upon Avon

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].