Netanyahu, the Joint List and a history of demonising the Palestinian voter

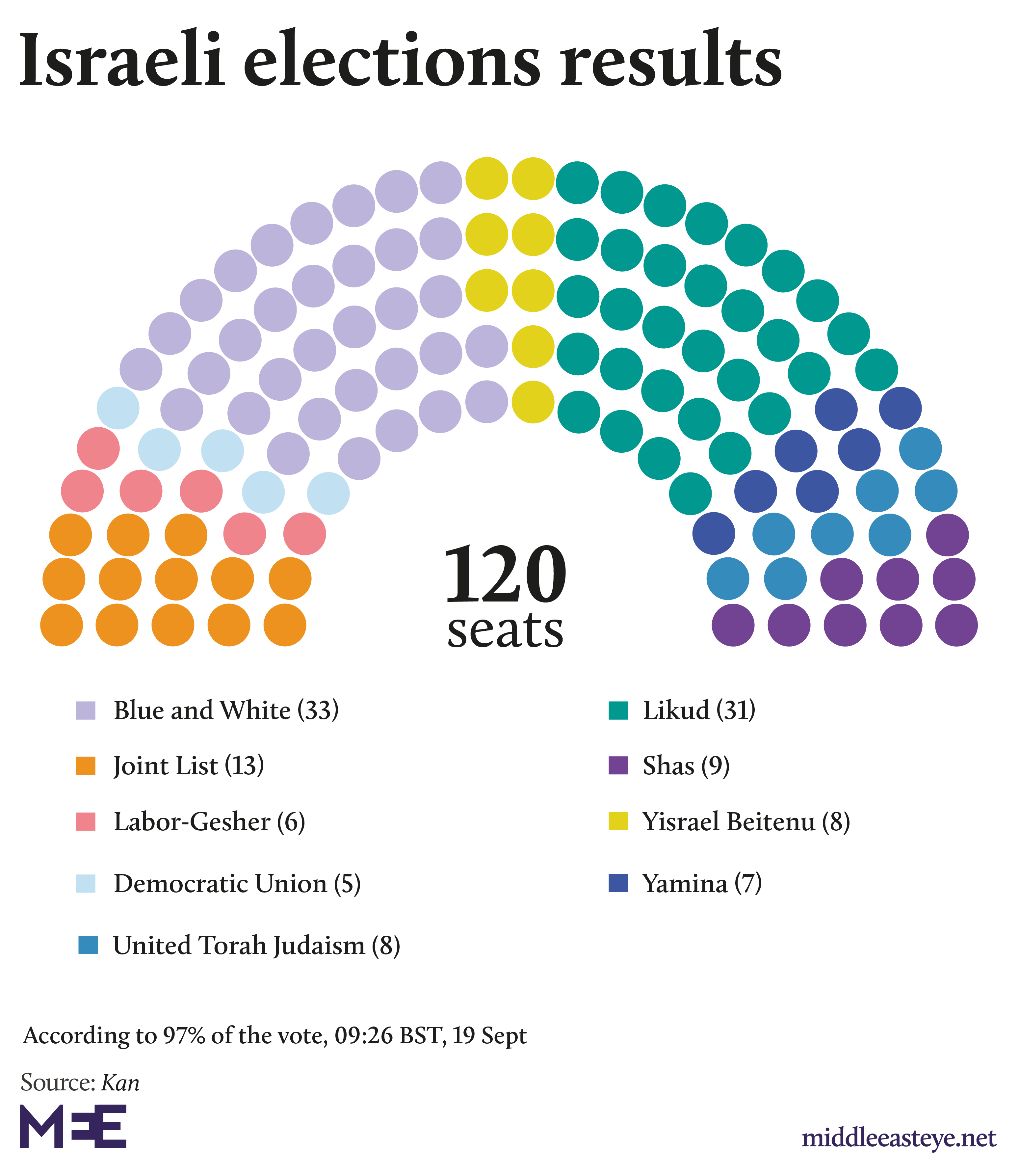

Israel’s re-run election last week revealed the bitter struggles within the Israeli right for dominance, between a coalition of religious and settler parties led by Benjamin Netanyahu and their opponents in the secular Blue and White party of army generals.

The two sides pegged almost level, suggesting that Israel could face yet more deadlock after an earlier election in April failed to produce a clear winner. There is already talk of an unprecedented third election in the offing.

But the more Israeli Jewish society reaches stalemate, the more the country’s marginalised community of Palestinian citizens – a fifth of Israel’s population – finds itself dragged on to the political battlefield. Israel’s 1.8 million Palestinian citizens have now been thrust into the heart of a national conversation among Israeli Jews about a supposed threat the minority poses to the country’s political life.

Endorsing Gantz

That was all the more so after a weekend in which 10 of the Joint List party’s 13 legislators, representing most of the Palestinian minority, decided to prefer one side in what Israeli Jews regard as their own tribal divide.

The more Israeli Jewish society reaches stalemate, the more the country’s marginalised community of Palestinian citizens finds itself dragged on to the political battlefield

They backed Blue and White leader Benny Gantz for first shot at trying to form a coalition government as prime minister. The List’s leader, Ayman Odeh, explained that they had taken the decision “to put an end to the Netanyahu era."

It was no easy matter, however, given that Gantz headed the military when it wrecked Gaza in 2014, sending it, in his words, “back to the Stone Age”.

Netanyahu immediately leapt at the chance to characterise Gantz, his main opponent, as getting into bed with “those who reject Israel as a Jewish and democratic state and praise terrorists”. He demanded that Gantz join him in a broad unity government of Jewish parties.

Gantz himself was reported to have responded to the Joint List’s endorsement coolly.

Political "traitors"

The reaction to the Joint List’s decision was not surprising. For years, Jewish legislators, especially on the right, have questioned the legitimacy of Palestinian parties exercising any influence on Israeli politics. Palestinian representatives in the Israeli Knesset have regularly been labelled "traitors" over their criticism of government policy.

But the incitement has been dangerously expanded over the past four years, reaching new peaks in this month’s election campaign. Now the debate is not just about the role of the Palestinian parties but also whether it is legitimate for the Palestinian public in Israel to participate in the democratic process.

This has always been the subtext of Jewish politicians’ discourse that Palestinian parties have no role to play in shaping the country’s politics. After all, it is Palestinian voters who send the Palestinian parties to the parliament.

But during election campaigns Israeli leaders have recently started to make that point explicit – and no one more so than Netanyahu.

‘Stealing the election’

The degree to which this notion is gradually being cemented in the Jewish public’s consciousness was underscored in this month’s campaign. Netanyahu repeatedly asserted that Palestinian voters in Israel were trying, in his words, to “steal the election”.

Now the debate is not just about the role of the Palestinian parties but also whether it is legitimate for the Palestinian public in Israel to participate in the democratic process

Netanyahu first inserted this idea into the 2015 campaign, when he warned Jewish voters on polling day that the “Arabs are heading to the polling stations in droves”.

In April’s election he extended the theme, implying that voting by Palestinian citizens constituted a kind of fraud that required monitoring. He violated election laws by sending Likud activists into more than 1,000 polling stations in Palestinian communities armed with body cameras.

Goaded by Netanyahu about colluding with the Palestinian parties, Gantz responded in typical fashion: he rejected any possibility of such cooperation. That has been the standard approach of Israel’s main Jewish parties for decades.

In his silence, too, Gantz offered implicit consent to Netanyahu’s demonising not just of the Palestinian parties but of the Palestinian electorate. He failed to challenge Netanyahu’s insinuation that Palestinian voters were "stealing" the election simply by voting.

Arabs and annihilation

Netanyahu went further still in this most recent election. Desperate to win a far-right majority so he could pass a law conferring on himself immunity from an impending corruption indictment, the prime minister turned the threat posed by Palestinians voters to his own political fortunes into a general, existential threat facing all Israeli Jews.

His Facebook page sent out an automated message to followers claiming that “the Arabs” – including Palestinian citizens – “want to annihilate us all – women, children and men”. That went further even than the incitement of his former defence minister and notorious Arab hater, Avigdor Lieberman, leader of the Yisrael Beiteinu party.

Days before Netanyahu’s “droves” comment at the 2015 election, Lieberman called for the beheading of Palestinian citizens - but only those who showed disloyalty to the state.

Lieberman is expected to be the kingmaker in the current post-election negotiations.

Judicial sanction

In a sign of how normalised Netanyahu’s incitement against Palestinian citizens is becoming, it was effectively given sanction during the campaign by one of the most senior judges in the land.

Hanan Melcer, a justice in the supreme court, is the current chair of the Central Elections Committee, which polices the way Israeli elections are conducted.

In the campaign’s final days, Netanyahu’s Likud party appealed to Melcer to stop the activities of a small charity, Zazim, comprising mostly left-wing Israeli Jews concerned about the state of Israel’s threadbare democracy.

It is often overlooked that, when Netanyahu warned in 2015 that the “Arabs are heading to the polling stations in droves”, he was actually blaming Israeli Jewish “leftists”. He accused them of “bussing Arabs” to polling stations.

His “electoral fraud” narrative in this latest election was intended to entwine these two themes. He wished to suggest that his political opponents, so-called “leftists”, were colluding with Israel’s enemies – the Arabs who wish to “annihilate us all”.

Disenfranchised Bedouin

The only practical example Netanyahu could offer of such “leftists” were those in Zazim.

The charity’s volunteers have in the past tried to help several thousand Bedouin citizens living in remote areas of Israel’s south, in the Negev, to reach their assigned polling station.

Many tens of thousands of Bedouin – among the poorest population in Israel – were effectively disenfranchised by the Israeli authorities decades ago. Their ancestral communities were criminalised in a continuing attempt to seize their lands.

Bedouin inside these “unrecognised” villages are not allowed to build homes – they have to live in tents or tin shacks – and are denied basic services like water and electricity. Although they are citizens, they are not allowed polling stations in their communities either.

To vote, therefore, they must travel long distances to recognised villages. Many thousands without transport have no hope of being able to cast a ballot.

No bussing of voters

Zazim, therefore, raises money to hire buses on election day to ferry these Bedouin citizens to far-off polling stations so they can exercise their democratic right.

Perversely, Melcer agreed with Netanyahu and Likud that Zazim’s efforts to help the Bedouin to vote was not protecting a basic democratic right – as Israel’s attorney general had earlier contended – but partisan “political activity”.

Melcer insisted that, if Zazim wanted to help the Bedouin vote, it had first to register as a political organisation, jeopardising its other social justice activities and burdening it with tight restrictions on fundraising. In the end, Zazim abandoned its transport programme for the Bedouin, and Netanyahu’s “Arab electoral fraud” narrative received a major shot in the arm.

Palestine gerrymandered

As Melcer’s ruling illustrates, Netanyahu’s claims of election fraud have not emerged in a vacuum. They are the latest and most cynical steps in long-running efforts by Jewish officials of all political stripes to neutralise the political influence of Palestinian citizens.

That began with the mass expulsions by the Israeli army of Palestinians in 1948 to create a Jewish state on the ruins of their homeland. The small Palestinian population that survived the ethnic cleansing operations – termed the Nakba, or Catastrophe – were the ancestors of today’s Palestinian minority.

The Nabka was primarily an exercise in the re-engineering of the region’s political and social landscape – an act of gerrymandering on a vast scale.

Palestinians were expelled outside the new borders and then Jews encouraged to immigrate as a replacement population. Overnight the Palestinians were transformed from the overwhelming majority into a small minority.

In Israel’s first three decades the vote for Palestinian citizens was entirely hollow

That was why Israel could allow its unwelcome new Palestinian citizens to participate in elections, even as they were subjected to draconian military rule in Israel’s first two decades.

In practice, their vote counted for nothing, paving the way for Israel to steal their lands and impose systematic discrimination in almost every sphere of life. To this day, the overwhelming majority of Palestinian citizens live in separate, ghettoised communities and are taught in a segregated education system.

Voting as window-dressing

In fact, in Israel’s first three decades the vote for Palestinian citizens was entirely hollow. It meant casting a ballot for special “Arab lists” of legislators offered up by the main Jewish Zionist parties.

Israel gradually liberalised that policy, but 15 years ago Asad Ghanem, a leading Palestinian scholar in Israel, described to me his community’s participation in elections for the parliament as little more than “symbolic” and “window-dressing”.

That was certainly how Israel’s Jewish politicians saw it. They were relatively happy for the Palestinian minority to vote, if only because the parties they elected had no role to play inside a parliament dominated by Jewish parties.

Rabin’s Oslo "betrayal"

But once Israel entered the Oslo process in the early 1990s, the role of Palestinian parties started to change.

At the time, Yitzhak Rabin became the first Israeli leader to engage diplomatically with the Palestinian leadership in exile. It was widely assumed that those talks would lead to the creation of a Palestinian state in the occupied territories.

Once Israel entered the Oslo process in the early 1990s, the role of Palestinian parties started to change

There appeared to be little enthusiasm for this process among a majority of Israeli Jews. Rabin, under pressure from the United States and Europe to pursue the Oslo track, was forced to rely on Palestinian parties to prop up his minority government from the outside so it could pass the necessary Oslo legislation.

The right expressed outrage both at the idea of ceding Israel’s supposedly divinely promised lands to the Palestinians and at relying on “Arabs” – Israel’s Palestinian minority – to pass such legislation. This betrayal, as it was perceived by the right, including by Netanyahu, led ultimately to Rabin’s assassination in 1995.

Decline in turnout

Through the 1990s and early 2000s, many Israeli Jews were concerned about Palestinian parties “meddling” in an Oslo process they believed should be decided by Jews alone.

Ironically, concerns about the influence of Palestinian citizens have only deepened over the past decade – at a time when no one in Israel is considering a peace process or talks with the Palestinian leadership in the occupied territories.

And in another paradox, such fears among the Jewish populace intensified at a time when the turnout among Palestinian voters in Israel fell to the lowest levels ever. In April, less than half the community cast a ballot, compared to more than two-thirds of Israeli Jews.

The rapid decline in voting among Palestinian citizens chiefly reflected the sense that there was no longer an Israeli left to ally with. Moreover, a series of moves from Netanyahu's government sought to alienate Palestinian voters.

Legislators face expulsion

The first move was the Threshold Law of 2014, which raised the electoral threshold to a point at which none of the four Palestinian parties could pass it. In a classic example of unintended consequences, however, the four combined into a Joint List, becoming the third largest party in the parliament after the 2015 election.

In response, the parliament passed the Expulsion Law of 2016, which empowered a two-thirds (Jewish) majority to expel any legislator whose politics offended them – effectively a sword hanging over every Palestinian member of the parliament.

But even these initiatives have proved insufficient. For Netanyahu and the far-right, the need to neutralise the Palestinian parties – and the voters who elect them – has become ever more pressing.

A decade of rule by Netanyahu and the religious right has provoked a backlash from the secular Israeli Jewish public. They are mostly right-wing and anti-Palestinian, but nonetheless they are tired of Netanyahu’s croneyism and his reliance on extremist religious and settler parties.

They are nostalgic for the days when Israel abused Palestinians quietly and stole their land less ostentatiously.

Paralysed Jewish politics

Representing a minority of the Jewish public, the secular parties cannot win power alone. In April all they managed – and may do so again – is to combine their votes with the Palestinian public’s to block Netanyahu and the religious right from forming a government.

That is why Israel is currently deadlocked. The only apparent way out is a so-called unity government between the secular generals of Blue and White and Netanyahu’s Likud. But the generals may insist on the price being Netanyahu’s ousting.

So while Palestinian voters can still not influence Israeli politics directly or in their own interests – let alone push it in the direction of peace – they can play a role in entrenching the divisions within Israel’s tribal politics. They can contribute to its paralysis.

And this is why Netanyahu and the far right need to diagnose the Palestinian minority’s right to vote in elections as a threat to the health of the Israeli Jewish body politic – one that needs to be removed before “the Arabs annihilate us all”.

Danger on the horizon

There is a further “danger” facing Israel’s Jewish majority in this period of political deadlock, as the Joint List’s decision to endorse Gantz this week highlights.

While Palestinian voters can still not influence Israeli politics directly, they can play a role in entrenching the divisions within Israel’s tribal Jewish politics

After many years of declining turnout among a Palestinian electorate disillusioned by Israeli national politics, there was a sharp reversal this week. In what largely amounted to a backlash to Netanyahu’s growing incitement, some 60 percent of Palestinian voters cast a ballot.

The more Netanyahu and the far right show they fear the Palestinian vote, the more Palestinian citizens may sense their vote has some value after all, if only in curbing the worst excesses of Jewish ultra-nationalism. Polls show that Palestinian citizens want their legislators to have more influence in the political system, and are even interested in them working with Zionist parties.

Shivers down the spine

Odeh, head of the Joint List, has taken note. Rather than opting out of Israeli politics as his predecessors have done, he has indicated a readiness to change approach by recommending Gantz.

Either the Joint List helps Gantz oust Netanyahu and the settlers, or it becomes the opposition to a unity government of the broad Jewish right

But further, if there is a unity government between Blue and White and Likud, as many Israeli Jewish politicians favour, the Joint List would gain a different sort of power by becoming the largest opposition party by default.

Odeh has said he would willingly become the official leader of the opposition, the first Palestinian citizen to hold the position. That would entitle him to security briefings by the prime minister and the army command, give him access to visiting heads of state, and a parliamentary platform to speak immediately after the prime minister.

The very idea sends a shiver down the spine of many Israeli Jews.

There have already been discussions about how to ensure such an eventuality does not take place. As commentator Gideon Levy observed facetiously this week: “If Odeh cannot head the opposition, then wouldn't it be better to bar Arabs from serving in the Knesset altogether? If they will always be suspected of treason, then they don’t belong in the legislature.”

More demonisation?

It looks as if Odeh and the Joint List could inadvertently gain crucial political influence whatever the outcome of coalition negotiations. Either the Joint List helps Gantz oust Netanyahu and the settlers, or it becomes the opposition to a unity government of the broad Jewish right.

Either of these developments risks inflaming Israeli Jewish sentiment against the Palestinian minority. The active involvement of Palestinian citizens in shaping Israeli democracy threatens to expose the contradictions at the very heart of a “Jewish and democratic” state.

Netanyahu has introduced new levels of incitement against the Palestinian minority in Israel. But paradoxically it may be his departure from Israeli politics that heralds a period of even greater demonisation of the country’s Palestinian citizens.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].