Twitter executive for Middle East is British Army 'psyops' soldier

The senior Twitter executive with editorial responsibility for the Middle East is also a part-time officer in the British Army’s psychological warfare unit, Middle East Eye has established.

Gordon MacMillan, who joined the social media company's UK office six years ago, has for several years also served with the 77th Brigade, a unit formed in 2015 to develop “non-lethal” ways of waging war.

The 77th Brigade uses social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, as well as podcasts, data analysis and audience research to conduct what the head of the UK military, General Nick Carter, describes as “information warfare”.

Carter says the 77th Brigade is giving the British military “the capability to compete in the war of narratives at the tactical level” and to shape perceptions of conflict. Some soldiers who have served with the unit say they have been engaged in operations intended to change the behaviour of target audiences.

What exactly MacMillan is doing with the unit is difficult to determine, however: he has declined to answer any questions about his role, as has Twitter and the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MoD).

Twitter would say only that “we actively encourage all our employees to pursue external interests”. The MoD said that the 77th Brigade had no relationship with Twitter, other than using it for communication.

'Using non-lethal engagement... as a means to adapt behaviours of the opposing forces and adversaries'

- The British Army

The 77th Brigade's headquarters are located in Hermitage, Berkshire, west of London. Its creation combined several existing military units such as the Media Operations Group and the 15 Psychological Operations Group.

At its launch, the UK media was told that the new unit of “Facebook warriors” would be around 1,500 strong, and made up of both regular soldiers and reservists. In recent months, the army has been approaching British journalists and asking them to join the unit as reservists.

While clearly engaged in propaganda, the MoD is reluctant to use that word to describe the unit’s operations.

Instead, the British army’s website describes the 77th Brigade as “an agent of change” which aims to “challenge the difficulties of modern warfare using non-lethal engagement and legitimate non-military levers as a means to adapt behaviours of the opposing forces and adversaries”.

MacMillan, whose editorial responsibilities at Twitter also cover Europe and Africa, was a captain in the unit at the end of 2016, according to one British army publication. The MoD will not disclose his current rank.

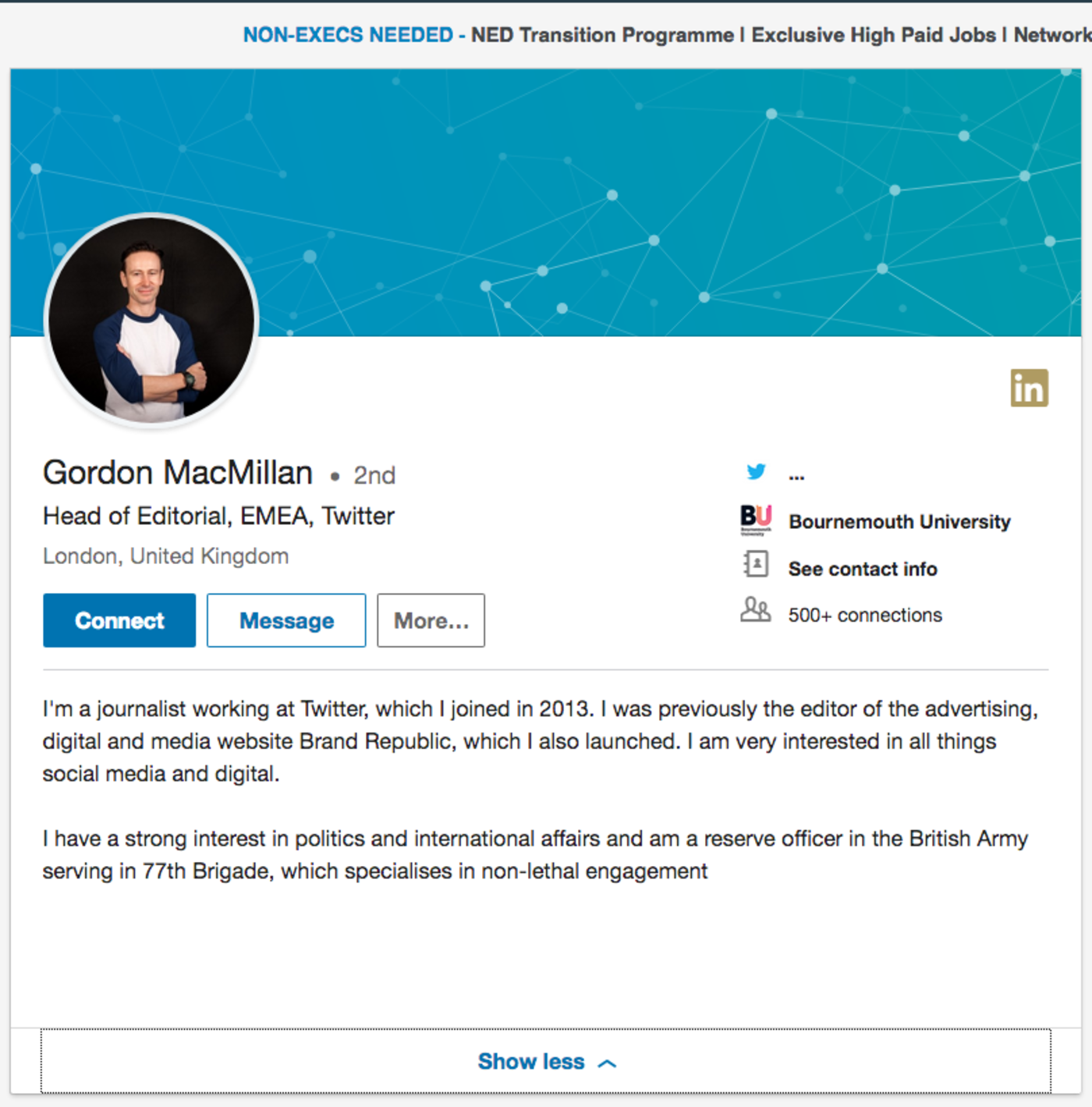

His involvement with the 77th Brigade was made public when he disclosed it on his page at LinkedIn, the online professional networking site.

As well as outlining his responsibilities at Twitter, MacMillan wrote that he had an interest in politics and international affairs, had trained at Sandhurst, the British military academy, “and am a reserve officer in the British Army serving in 77th Brigade, which specialises in non-lethal engagement”.

His page has recently been edited to remove all references to his service with 77th Brigade.

77 Brigade: 'Remarkable talent'

MacMillan is not alone in outlining his involvement with the unit on his LinkedIn page. One former 77th Brigade officer has said on his page that he served with the unit’s “Information Warfare Teams” in the UK, Bosnia, France, Kenya and Albania.

Another, a former officer in the UK’s Royal Navy, has said that while serving with the 77th Brigade he was “the lead component on Behavioural Change for the Middle East Region and Counter-Radicalisation”.

This person - who is not a Twitter employee - added that his duties included “advising the Jordanian Armed Forces and Royal Hashemite Court” and that he was also seconded to the Strategic Effects Team at the UK Ministry of Defence. Contacted by MEE, he declined to elaborate.

Some insight into the unit’s methods was provided by Carter in a speech last year at the Royal United Services Institute, a London-based military and defence think tank.

“In our 77 Brigade … we have got some remarkable talent when it comes to social media, production design, and indeed Arabic poetry,” he said.

“Those sorts of skills we can’t afford to retain in the regular component [of the army] but they are the means of us delivering capability in a much more imaginative way than we might have been able to do in the past.

“We also, though, need to continue to improve our ability to fight on this new battlefield, and I think it’s important that we build on the excellent foundation we’ve created for Information Warfare through our 77 Brigade which is now giving us the capability to compete in the war of narratives at the tactical level.”

Carter went on to quote a recently published book, War in 140 Characters, in which journalist David Patrikarakos observes that during the war in Ukraine, “counter intuitively, it mattered more who won the war of words and narratives than who had the most potent weaponry”.

Covert influence campaigns

The Arab Spring, almost a decade ago, demonstrated that protestors could topple tyrants after sharing information on social media. There has also been a wider realisation in recent years that technology has shifted power from national governments and media companies towards networks of individuals.

Many observers assumed it was only a matter of time before the state began to counter that trend. “Homo digitalis may challenge the state,” Patrikarakos writes, “but the state will always fight back.”

Covert influence campaigns being mounted by states such as Russia and China have been identified and exposed on several occasions.

In August, Facebook announced that it had shut down multiple accounts run by a company called New Waves, based in Cairo, and an Emirati firm, Newave.

The two companies worked in concert, disseminating messages supportive of the foreign policy objectives of Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

Subsequently, The New York Times reported that New Waves was run by a retired military officer who describes himself as an “Internet wars researcher”, while the Emirati company operated from a government-run media complex in Abu Dhabi.

Together, they were reported to have managed 361 compromised accounts and pages with a reach of 13.7m people, spending $167,000 on advertising and using false identities to disguise their role.

One focus for their social media campaigns was Sudan, where democracy advocates noticed a stream of pro-military tweets. Another was Libya, where accounts controlled by the two companies promoted General Khalifa Haftar, commander of the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA).

Twitter also announced in September that it had suspended hundreds of coordinated accounts which, it said, breached its “platform manipulation” policies. These had operated from Spain, Ecuador and China, as well as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

The company said in a statement: “We will continue to enhance and refine our approach to disclosing state-affiliated information operations on our service.” It also promised greater disclosure of data about state-affiliated information operations.

Twitter 'one of many social media platforms used'

The British Army declined to disclose anything to Middle East Eye about MacMillan’s duties with the 77th Brigade, or say whether Twitter helps it, in Carter’s words, “to compete in the war of narratives at the tactical level”.

It would also not say anything about the military’s use of Arabic poetry, as revealed in the general’s speech. Nor would it say anything about the military initiative intended to achieve “behavioural change” among audiences in the Middle East.

In a statement, an army spokesperson told Middle East Eye: “There is no relationship or agreement between 77th Brigade and Twitter, other than using Twitter as one of many social media platforms for engagement and communication.

“The Army does not comment on the specific activities of reservists working within the division.”

The identities of the Twitter accounts which the 77th Brigade uses for engagement and communication remain unclear, however. The unit’s acknowledged account has been locked since it was hacked earlier this year, with the result that only approved followers can see its tweets.

Twitter also declined to answer questions about its executive’s British Army duties, despite its pledge to disclose further information about state-affiliated information operations.

In a statement, the company said: “Twitter is an open, neutral and rigorously independent platform. We actively encourage all our employees to pursue external interests in line with our commitment to healthy corporate social responsibility, and we will continue to do so.

“We also proactively publish datasets on potentially state-backed foreign information operations on the service. We deliver this in conjunction with partners in government, civil society and academia, to promote a better social understanding of these threats.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].