Pressured by Assad and assaulted by Turkey, can the Rojava project survive?

Ever since it first emerged on the political scene in the early days of the Syrian civil war, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its armed wings - the People's Protection Units (YPG) and Women's Protection Units (YPJ) - have always claimed to be more than simple political advocates for Syrian Kurds.

After taking control of large swathes of northern Syria following the pullout of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's forces in 2012, the Kurds announced their intention to implement a policy of democratic confederalism.

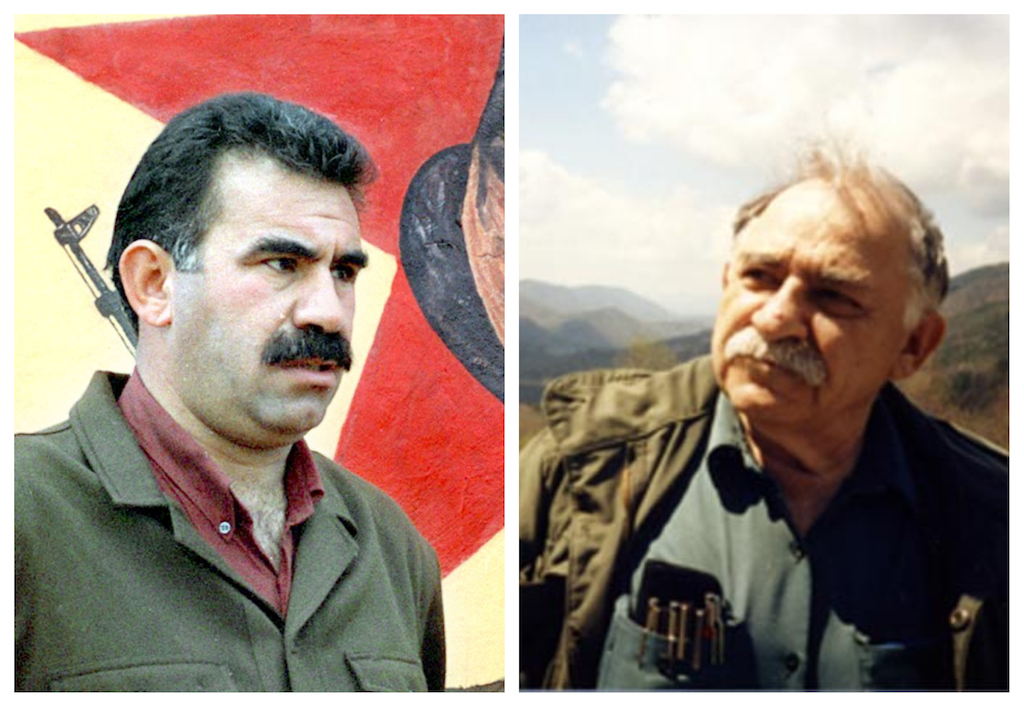

That policy took the form of a decentralised democracy coupled with feminism, secularism and eco-socialism, based on the philosophy of Turkey-born Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan, one of the founders of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).

They claimed that Ocalan's ideas, and their implementation on the ground, could be a model for the region that would transcend divisions on the basis of gender, ethnicity and religion.

On Sunday, that vision received a severe blow. Faced with the prospect of a Turkish assault on the fragile autonomous administration they had established in the northeast, the PYD signed a deal with Damascus that saw Syrian government forces deployed into areas controlled by the group.

Berivan Xalid, the co-chair of the executive council of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, told Middle East Eye that there had been no discussion on how the new agreement would affect the governance of northern Syria.

"Our, and the regime’s objectives, is the protection of Syria’s borders from Turkish invasion and Syria in general - the discussion was only about military affairs," Xalid said.

"We as the Autonomous Administration will continue to run things as before, even under bombardments. And we’ll see if in the coming days more talks will take place."

Significant gains for Assad

However, others see little option for Rojava - the Kurdish name for the region, meaning "West", as in the western region of Kurdistan - now that it is squeezed between a hostile Turkey and a Syrian government eager to recapture all the land it had lost since 2011.

'We as the Autonomous Administration will continue to run things as before - even under bombardments'

- Berivan Xalid, Autonomous Administration

Syria analyst Danny Makki said the new deal would hand over significant amounts of northern Syria back to Damascus, including "energy sources, military airports, administrative buildings and border areas".

"In addition to the cities of Kobane and Manbij, Assad will also get large parts of Raqqa and be allowed to use SDF territory freely until a larger comprehensive accord is reached," he told MEE.

"All in all, it has given Damascus more land in one day that it was able to capture in years of fighting."

A new kind of politics?

The PKK, originally founded in 1978 by Kurds in Turkey, had originally adhered to a hardline Marxist-Leninist ideology sympathetic to the Soviet Union and Cuba.

The goal was an independent socialist Kurdistan carved, initially, out of Kurdish-majority areas of southeastern Turkey.

However, after Ocalan's capture in 1999, the ideology began to shift.

Writing from prison, Ocalan claimed to have received inspiration from the works of Murray Bookchin, an American anarchist and libertarian socialist writer who died in 2006 and wrote about the need to transition to a post-capitalist society based on local council-based democracy and ecology.

The collapse of the central government's power in Syria since the beginning of the war provided an opportunity to actually implement the ideas on the ground, say the supporters of the Rojava administration.

Janet Biehl, a writer and activist who was Bookchin's partner at the time of his death, said she had travelled to Rojava a number of times and witnessed the new structures being put into action.

'This is a beleaguered people. They’re at war. They can’t run everything past every commune. There’s a military leadership'

- Janet Biehl, writer

"The original idea was that decisions would be made at the bottom and power would flow bottom-up. That was how Bookchin designed it to be, it was supposed to be a bottom-up democracy," she told MEE.

Biehl said each commune - usually comprising a village or a set number of city households - had a number of committees focusing on peace; security; education; economy; culture and art; women; health; infrastructure; social affairs and diplomacy.

With that as the base, the rest of the democratic structure consisted of neighbourhood assemblies, city assemblies, canton assemblies and the executive council at the top of the structure.

"I live in Vermont and I used to go to town meetings with Bookchin, citizen assemblies here, and it never in a million years occurred to me, or him, that I would one day be visiting the equivalent of a Vermont town meeting in the Euphrates valley," said Biehl.

Since 2014, more than 11,000 fighters associated with the PYD - including members of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-Arab coalition backed by the US - have died fighting against the Islamic State group in Syria.

Their battle with the much-feared group, with men and women from a multitude of different religious and ethnic groups fighting side by side, made them highly popular around the world, even as much public sympathy seemed to drain away from other Syrian opposition groups who were increasingly perceived as fundamentalist and sectarian.

But the PYD's less than antagonistic relationship with the Syrian government has long been a point of criticism from the Syrian opposition, who have previously accused the PYD of outright collusion with the Assad administration.

In addition, despite the open advocacy of localised democracy, some groups - including Kurdish ones - have claimed that the PYD largely controls Rojava as a one-party state and forces locals into conscription.

“The YPG seizes civilians’ houses if they need to," said Abdullah Kedo, a member of the Kurdish National Council - a group close to the Syrian opposition - speaking to the Turkish newspaper Hurriyet last year.

"They raid the offices of Kurdish political parties who oppose those acts and ban those parties. They also forcibly recruit young men and take them to battle zones in Raqqa.”

Though the PYD has longed denied such accusations and has pointed to the participation of other political parties in the Autonomous Administration's democratic bodies, the use of conscription has long been controversial - particularly considering the high death toll incurred among those fighting.

"This is a beleaguered people. They’re at war. They can’t run everything past every commune. There’s a military leadership," said Biehl.

"But people understand from the writings of Ocalan that this whole structure is structured to empower people, and even if they, in the self-administration, have positions of power, they pay close and good attention to the wishes of people from below."

The end of Rojava?

For decades, Kurdish groups have relied on outside powers to back them in their struggle for autonomy and independence. Eventually, however, these powers usually lose interest once their own short-term goals are achieved.

The apparent green light that was given by US President Donald Trump on 7 October for Turkey to launch Operation Spring of Peace has so far seen dozens of civilians killed, mostly on the Kurdish side, and displaced at least 160,000 people.

Under such pressure, there were few options left for the Autonomous Administration to take - even if that meant the leadership "assimilating into the government in Damascus", Makki told MEE.

He added that a power-sharing agreement actually suited Damascus better at the moment, as it was currently not in the interest of the Assad government to press matters in northern Syria because it does not have the capacity to rule large swathes of the land immediately.

However, "only time will tell if they keep to their word", Makki said.

"Unfortunately for the PYD, it would never have been able to survive [long-term] without brokering a deal if another actor emerged victorious in the Syrian conflict," said Makki.

"At one point that could have been the opposition, but after the Russian intervention in 2015, it became apparent the government would win and the Kurds would be forced to make some sort of deal if they were abandoned by the US," he explained.

Although on Tuesday it was reported that the SDF had managed to push back against Turkish forces in the town of Ras al-Ain, prospects for Rojava - attacked by Turkey, abandoned by the US and now reliant on Assad - appear bleak.

But Xalid is clear that she believes the gains of Rojava will endure - even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

"After all the sacrifice and achievements of the Autonomous Administration, and after establishing these institutions, and after 11,000 martyrs, we are managing five million people in north and east Syria," she said.

"So of course, after nine years of these achievements as the Autonomous Administration, we will maintain our achievements and the blood of our martyrs because we achieved all this through them."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].