From colonialism to Laicite: France continues to wage war on Muslim women

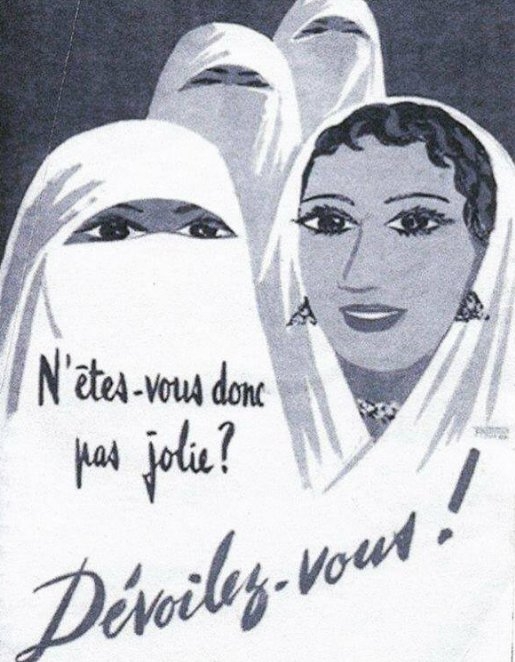

During the French occupation of Algeria, Frantz Fanon wrote about France’s gendered approach to maintaining its colonial grip: "If we want to destroy the structure of Algerian society, its capacity for resistance, we must first of all conquer the women; we must go and find them behind the veil where they hide themselves and in the houses where the men keep them out of sight."

This approach, it seems, is far from a thing of the past for the French state, its extreme version of secularism or Laicite and society.

There had already been 85 televised debates on the hijab across French news channels, an unbelievable 286 invited guests to speak on the topic, and not a single one was a woman wearing a veil

Indeed, once again, the last week was plagued with hundreds of commentators and dozens upon dozens of televised as well as radio debates and headlines on Muslim women and their right (or rather otherwise, as the case might be) to wear the hijab.

This avalanche of endless attacks, as has become so customary in the French context, unified a wide political spectrum, from the far left to the far right. Targeting one of the most oppressed groups in the country, it followed an incident on a school trip when a hijab-wearing mother dared to accompany her son to the regional parliament in Dijon.

Known as "Fatima", she found herself being verbally abused by politician Julien Odoul from the fascist National Rally party (formerly known as the National Front), who demanded that she removed her headscarf or not be allowed in the building.

Odoul’s tirade was tepidly resisted by the chair of the assembly, while other members awkwardly shifted around on their seats and made unconvincing demands for the NR representative to stop. In effect, the mother was left to face the assault alone, while trying to console her distressed child.

Neither was Odoul’s attack an aberration. It rests on the existing legislation that has aimed to bar Muslim women from public life in France by, for example, making it illegal in 2004 to access school while wearing a hijab.

France was, shamefully, also the first country in Europe to enforce the niqab/face-veil ban back in 2011.

Echoes of the colonial period

Simultaneously, last week also marked the anniversary of the Paris Massacres which took place on the 17 October 1961 during the Algeria war. Hundreds of Algerians who had been protesting for Algeria’s independence were murdered and their bodies were thrown in the Seine river by French police - under the command of Maurice Papon who had previously participated in the deportation of hundreds of Jews during WWII.

It took until the late 1990s for the events and death of even a small fraction of those killed to be recognised by the French state, and until 2001 for a commemorative plaque to be placed at the scene of the crime.

The fact that both events took place at the same time is telling. The resistance by the French state to commemorate and recognise its colonial violence and abuse directed against Algerians, both at home and abroad, plays an important role in masking the violence directed against Muslims in France today.

The treatment of Muslim women at the hands of the state in the present echoes the assaults on Algerian women under colonialism. Police violence against young Muslim men in the streets of France today echoes the police violence against migrant workers back then.

The social segregation of Muslim populations in the cités - low income suburbs - across the country today, echoes their ghettoisation in French slums throughout the colonial period.

Contemporary hatred

It is impossible for the state to recognise its past, because it never ended. Recognition would need to lead to justice and change. So, for example, the anniversary of the 1961 massacre should have seen both the state and public institutions utilising its commemoration to mobilise against contemporary hatred.

Instead, it was taken over by the replaying of the racism that marked the entire French colonial project, in Algeria and across other continents.

Odoul’s reaction, the mixture of rage and entitlement he hurled across the room at Fatima, summed up exactly where the country still stands on the liberation of its formerly colonised subjects. France has neither accepted, nor does it believe that people of colour deserve their freedom.

Its continued need for segregation and subjugation runs deep, and it is still, decades on from Algeria’s liberation, centred upon the control of Muslim women, their bodies, and their place in society.

The degradation of Fatima in that moment, as well as of her son who was so upset by the scene that he sought refuge in his mother’s arms yet made no impact on the fascist politician, was difficult to watch.

But walk along the streets of Paris – a supposed lively multicultural capital city – sporting a hijab, walk into a local bank or supermarket, and you’ll come to understand very quickly that the incident is no exception.

Six days after Fatima’s verbal assault at the regional assembly, the French paper Libération noted that there had already been 85 televised debates on the hijab across French news channels, an unbelievable 286 invited guests to speak on the topic, and not a single one was a woman wearing a veil.

In those debates, the question of what Muslim women should be allowed to wear, which rights should be taken away from them if they refuse to acquiesce, and what role the French state should play in their exclusion were all given free reign. In fact one journalist went as far as to compare the hijab to an SS uniform.

Open season

What is striking is that this open season on Muslim women and their right to participate in public life in France is not the preserve of the far right. Indeed, Odoul’s view has been normalised by liberal feminist arguments churned out in defence of the state-enforced unveiling since the early 2000s.

What is striking is that this open season on Muslim women and their right to participate in public life in France is not the preserve of the far right

Now, just as has been the case for the last two decades, these attacks, these exclusionary laws, the violence of the state, are repeatedly defended as an act of liberation of oppressed Muslim women, saving them from their barbarian husbands and fathers.

Much like the US promised to liberate Afghan women by bombing them, and colonialism promises to liberate its subjects by exploiting them to death, the French intelligentsia promises to liberate Muslim women by excluding them from public life, public debate, and employment.

The truth is that none of the interested parties parading behind the defence of Muslim women and secularism, deem hijab-wearing Muslim women worthy of entering a political or intellectual space in which they can put forward their own demands. The latest round of televised debates demonstrated this once again.

The resistance

Whilst Fatima is seeking justice through legal avenues, her experiences will continue to haunt all those struck by this particular event, and more widely, Muslim girls and women who are reminded that their bodies are a battlefield on which the French state continues to wage its war on people of colour.

Protests, social media outrage and international solidarity are important tools that undo the isolation felt by those impacted, while chipping away at the confidence and monolithic discourse of French Islamophobia.

One wonders if the French state has learned anything. Perhaps refusing to recognise its past makes it equally blind to learning the lessons from it. If French control of Algerian society was premised on controlling its women, it mainly succeeded in bringing Algerian women into the forefront of resistance against its rule.

Looking at Fatima, silently and courageously facing down the screaming deputy, while everybody else in the assembly squirmed uncomfortably, one could see the same process repeating itself.

She alone represented the resistance in that room, and the future end of their rule.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].