How Lebanon's 'circus regime' has started to crack

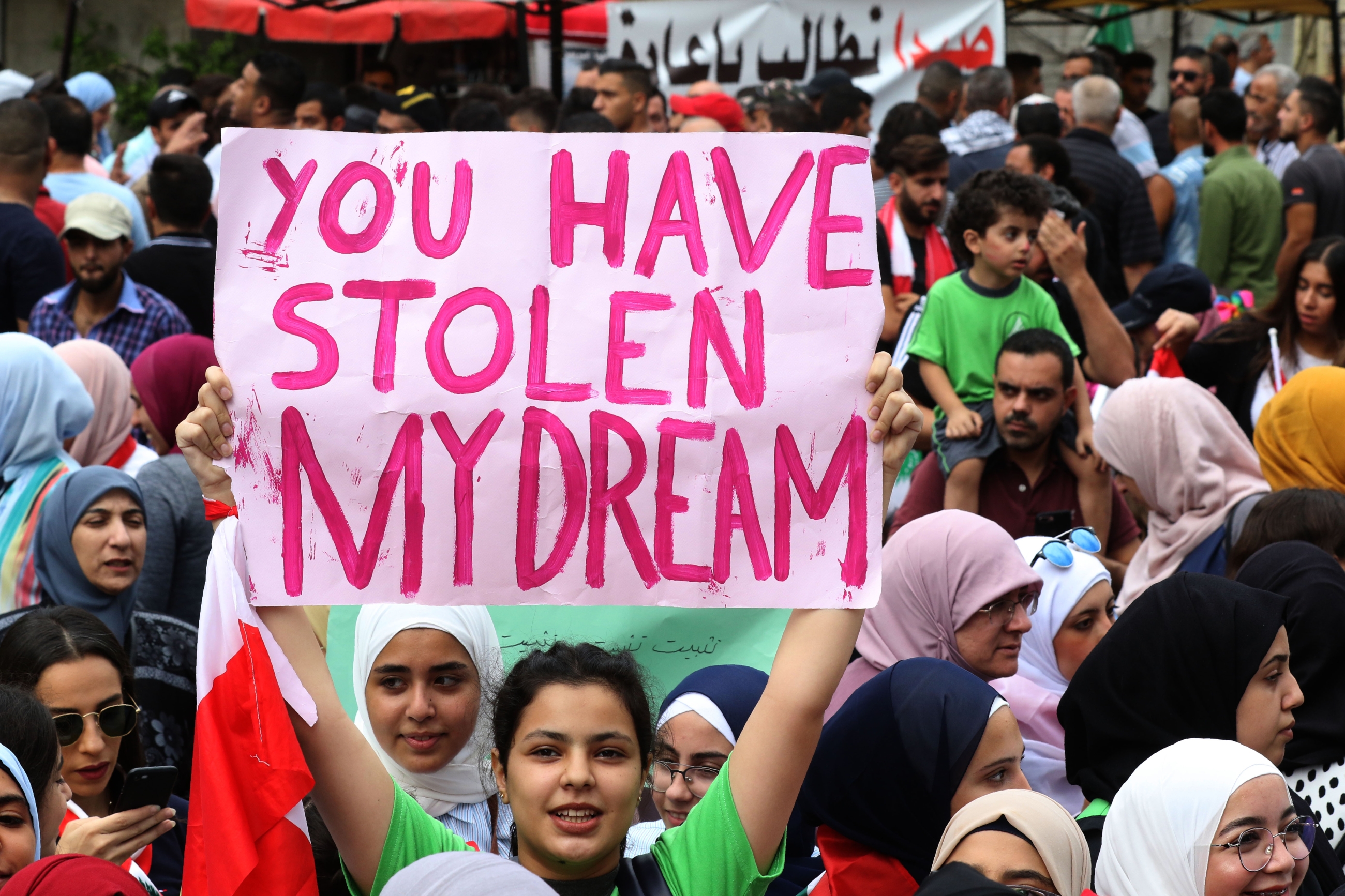

In Lebanon, rebels and popular movements have existed since time immemorial. Yet, this is the first time that the insurgent face of the people has revealed itself, apparently surprised by its own existence and annoyed at the delayed birth.

The ongoing demonstrations are emanating from the country’s collective practices of insubordination and subversion, generating a collective, purifying despair.

Many factors have contributed to the intensification of this despair. Based on a “casino economy”, the Lebanese regime - or what I call the “circus regime” - can no longer maintain its own clowns, the oligarchic leaders of sectarian groups, as the sclerotic system starts to crumble.

Paternalistic relationships

The Lebanese regime is built on the notion that “people” as a project is an impossibility in a country such as Lebanon. It is true that Lebanon has constitutional continuity, uncommon in the Arab world, and that the constitution recognises the people as “the source of authority and sovereignty” - but the people as a collective, active subject is fundamentally different from the people as merely a “source”.

As long as the country’s clownish leaders sustain paternalistic relationships with their communities, the notion of “the people” as a collective emancipation project remain impossible. But a new possibility recently came to light as paternalism itself became clownish, including the government’s imposition of a $6 monthly tax on the WhatsApp messaging service. This was a step too far, pushing the people’s class struggle to the next level.

The rising pauperisation has enlarged the category of vulnerable workers and unemployed people

This struggle has been facilitated by a few interconnected bankruptcies, including the collapse of the myth of the fixed exchange rate between the Lebanese pound and the US dollar. The Lebanese economy has been entangled in a vicious cycle of debt to cover debt, resulting in the mass subjugation of citizens to the public debt and personal loans.

For decades, the fixed exchange rate has created an illusory stabilisation, helping Lebanon’s central bank to contain market forces and construct a monstrous type of state capitalism. This, in turn, gave rise to a system that is neither subject to the forces of supply and demand, nor concerned with social justice or social protection, all while sustaining a large public sector.

Zero economic growth

This mafia-style system has exacerbated social inequalities. More gravely, in a time of zero economic growth, it has threatened the purchasing power and social security of the vast majority, reducing many to a form of “loan slavery”.

Class divisions have become more visible in recent years, from the country’s oligarchic billionaires right down to the proletarianised popular majority.

Most Lebanese citizens make their living from selling their labour, in addition to small-scale rentier resources, and conditions are getting worse. The rising pauperisation has enlarged the category of vulnerable workers and unemployed people.

In other countries, state capitalism comes with some degree of state economic control, coupled with economic support to a large popular base, usually expected to be loyal to the ruling regime. It is quite different in the case of Lebanese state capitalism, which is devoted to the oligarchy and where the regime and its loyal base are directly connected through sectarian structures.

With the recent US sanctions against Hezbollah, this system of oligarchic state capitalism has entered a vicious cycle, made even more difficult by the high risk and neoliberal financial engineering, pushing it faster towards the final stages of collapse.

Dismantling oligarchy

Lebanon’s current uprising is playing a strange game with the country’s flailing political and financial institutions. The insurrection started at the right moment, on the eve of the collapse, to simultaneously accelerate and prevent it. After all, who must pay for this collapse: the rich or the poor? And who is better positioned to overcome the disaster?

The merchant republic of the late Lebanese banker, journalist and politician Michel Chiha has degenerated into the oligarchic dystopia of President Michel Aoun, Speaker Nabih Berri, Prime Minister Saad Hariri, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, as well as Druze leader Walid Jumblatt and Samir Jajae, head of the Lebanese Forces party.

The people’s insurgence is a project to achieve a completely different republic, neither mercantilist nor oligarchic, both of which result in the marginalisation of the popular classes.

It is a zero-sum game, in a way. To give the people representation means to dismantle oligarchic rule. As protests rage on, the words of Chairman Mao hang heavy:

“A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.”

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].