This olive tree in Bethlehem has stood for 5,000 years - and this man is defending it

It has stood in this spot near Bethlehem longer than Christianity and Islam, since before the time of the prophets of the Holy Land.

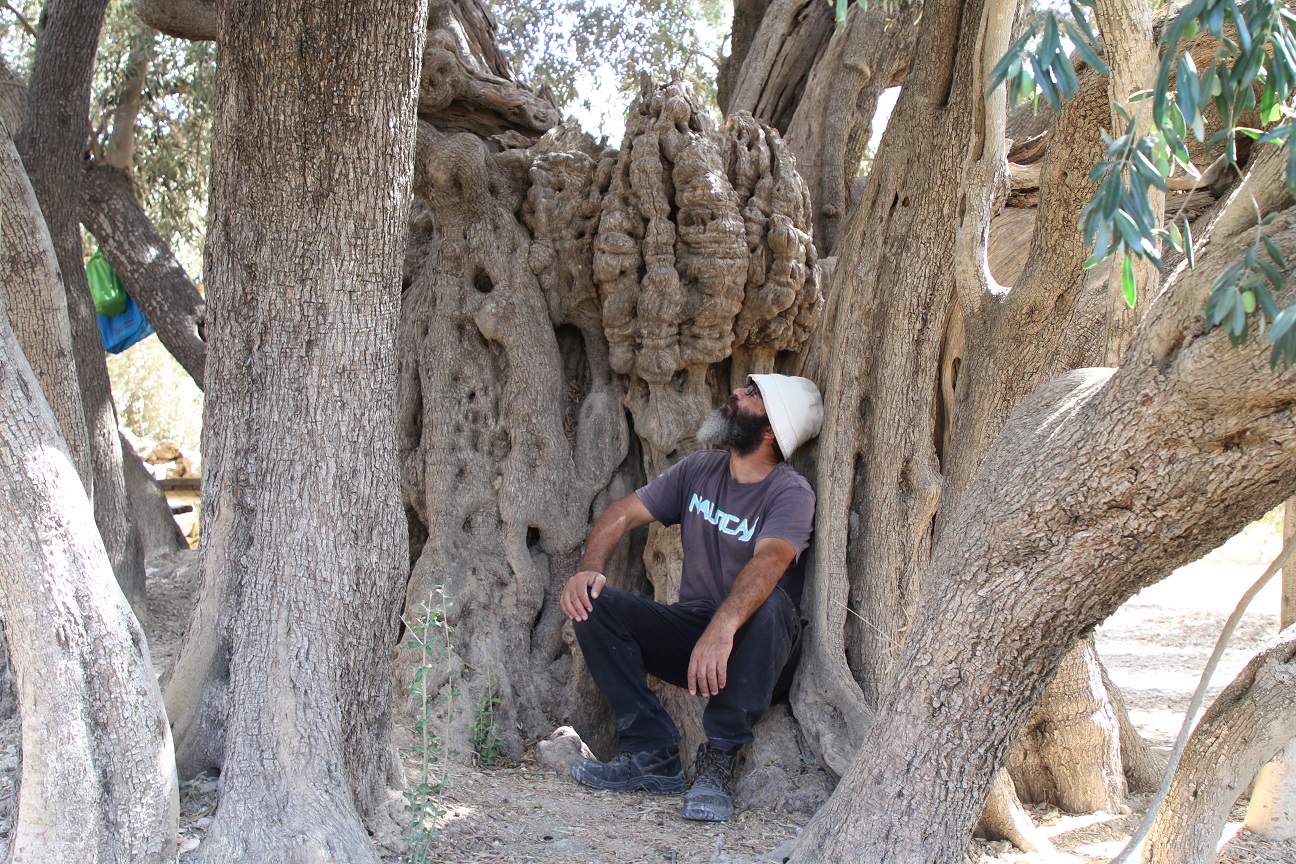

Circling slowly round this ancient olive tree, Salah Abu Ali carefully inspects every inch of it, before settling back on his chair in its shade.

Beside him, balanced on a log, is a plate of fruit he has freshly picked from his farm. Also within arms reach is a large bottle of water and the pot of hot coffee he prepares every day to offer visitors to the spot that has become his sanctuary.

Every morning at 6.30am, the 46-year-old walks to the site where the tree is located on his family’s plot of land. For the past ten years, he has been tasked with a grave responsibility: guarding the oldest and largest olive tree in Palestine.

The tree, which belongs to the Abu Ali family, lies in the Wadi Jwaiza neighbourhood of Al-Walaja village in Bethlehem, southwest of occupied Jerusalem.

Despite spending most of his time by the olive tree, Abu Ali says he is still awed by it. “The beauty and size of this tree are really special, it captivates the mind – it is the most beautiful tree in Palestine,” he tells Middle East Eye.

According to the Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture, the tree is estimated to be around 5,000 years old. It extends over 250 sq m, stretches to around 13 metres in height, and its roots extend some 25 meters into the earth.

'An occupation that has been around for tens of years will not uproot it'

- Salah Abu Ali

Over the years, the tree has been given a variety of nicknames; Abu Ali calls it “the fortress,” though it has also been dubbed “the old woman,” “the mother of olives,” and “Palestine’s bride.”

From their experience of farming, Palestinians know that the older the tree, the better the quality and taste of the olives - and the olive oil they produce. The head of the governmental Palestinian Olive Oil Council, Fayyad Fayyad, tells MEE that, while the olives of the oldest tree are no different to those of other trees, research shows that the larger and older the tree, the richer the olive oil.

“The age of the tree factors greatly into the taste and quality. The Al-Walaja tree produces very high-quality oil,” he says, adding that an investigation is ongoing into whether it could in fact be the oldest olive tree in the world.

The tree used to produce half a tonne of olives each year, but its output of olives has declined in recent years, says Abu Ali. “Last year, however, the olives only came up to 250 kilograms of oil. There have even been times when the tree did not produce anything.”

Another problem, Abu Ali says, is water: “The tree is thirsty. It is in need of large amounts of water due to its size, but these amounts are not available. The water spring is insufficient."

He has taken it upon himself to quench the tree’s thirst by extending a hose from the water spring nearby. But the supply there is dependent on rainfall and is particularly dry in summer. Over the past few years, he says the water has been decreasing.

“I try to sustain it by adding manure to the ground and tending to its surroundings. It hurts me to see it like this.”

Israeli expansionist policies

The tree stands just 20 meters from the Israeli separation and annexation wall, which was built over several phases starting from 2007.

Al-Walaja village is historically part of Jerusalem, and residents would regularly travel back and forth for their shopping, and for work. When Israel occupied east Jerusalem and the West Bank in 1967, it annexed large parts of Al-Walaja’s fields and lands.

'This tree is no less important than the al-Aqsa or Ibrahimi mosques'

- Salah Abu Ali

“[When the wall was erected], the Israeli occupation forces used a large number of explosives, without caution to the tree. We were very afraid that it would be effected, but it persisted, as it has for thousands of years – an occupation that has been around for tens of years will not uproot it,” says Abu Ali.

In October , the Israeli army’s wing responsible for civilian life in the occupied West Bank posted a message on Facebook about the tree, calling it the “oldest olive tree in Judea and Samaria”. The post angered activists, who saw it as an attempt to appropriate Palestinian history and heritage.

Fayyad says that the Israeli authorities, including both civil and military personnel, have visited the tree in the past, and that they took samples and measurements, which stirred fear among the families of Al-Walaja.

The families then requested the PA’s agricultural ministry to intervene by securing someone to guard the tree at all times.

While Abu Ali was already spending much of his week guarding it, the PA now pays him a monthly salary of around $410 to guard the tree every day.

‘Part of our identity’

Olive trees have long been at the forefront of Israel’s expansionist policies through its military occupation and settler-colonial project. The Al-Walaja olive tree is one of around 11 million olive trees in Palestine, according to the PA’s official information website.

The trees face a double threat to their existence, with the Israeli army systematically cutting down trees and Jewish settlers regularly carrying out acts of violence, including vandalism, against Palestinian towns and fields.

Such attacks increase during the olive harvest season between the months of October and November. In June 2019, the UN documented the cutting down of close to 400 Palestinian-owned trees in the same area during one incident of property demolition by the Israeli army.

“The occupation and Israel’s policies are built on fear,” says Abu Ali, explaining that such acts by Israel and its settlers are intended to drive Palestinians from their lands in fear of attacks. “We either defend our lands or we give up. This tree is a trust."

Inheriting love for the tree

The families of al-Walajah call it the “al-Badawi tree” – a reference to the Egyptian Sufi spiritual guide, Sheikh Ahmad al-Badawi, who was said to have visited the tree and to have tended to it for some years.

Abu Ali too considers the tree to hold spiritual significance. “If we do not preserve this tree,” he says, “we will be held accountable. This tree is no less important than the al-Aqsa or Ibrahimi mosques.”

The residents of Al-Walaja also consider the tree to be a source of good luck and blessings. According to Abu Ali, women would collect its fallen leaves to protect them from the evil eye. Every year, families sacrifice their sheep during the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha in the shade of the tree.

And despite the fact that he says his salary is barely enough to make ends meet, Abu Ali insists on guarding the tree, which he regards as symbolic of Palestinian perseverance.

“If this tree remains, then we will remain. This tree is part of our identity, and part of the conflict over which we fight the [Israeli] occupation.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].